The F. Hagger collection encompasses some 260 photographs of China in the early 1930s, as well as many of Japan, Singapore, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), North Borneo, Manila, India, Egypt, and others which are not on the Historical Photographs of China website. The album will be available for consultation at University of Bristol Special Collections.

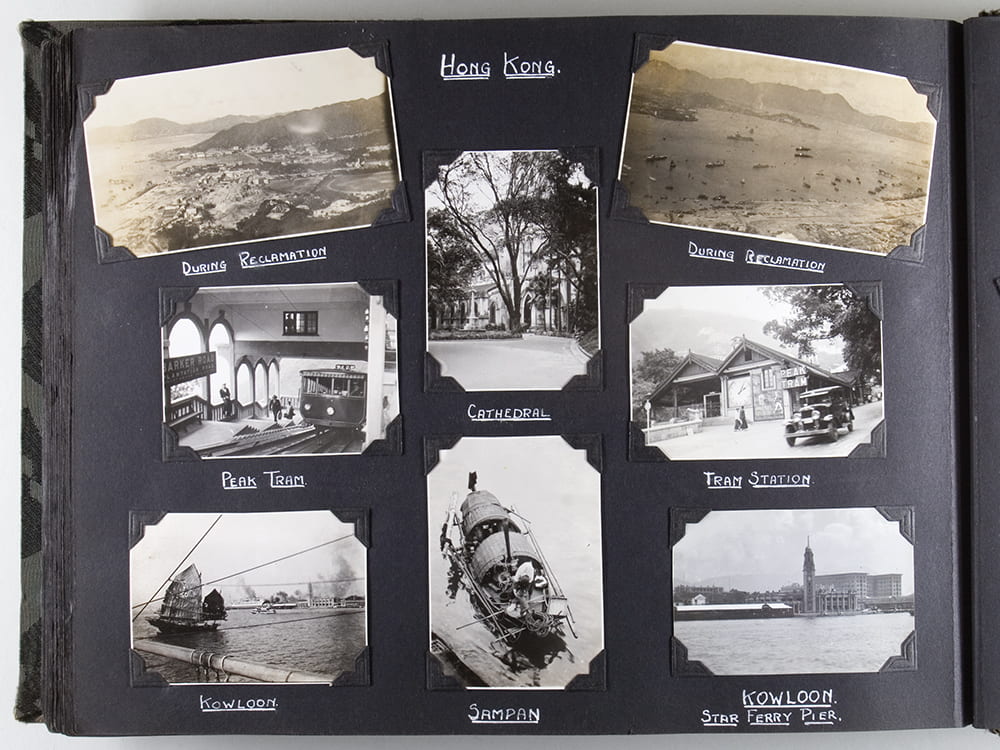

A neatly captioned page from Hagger’s album (HPC ref FH01), which has an olive green cloth cover, woven with a playing cards design, manufactured by Yeikwan.

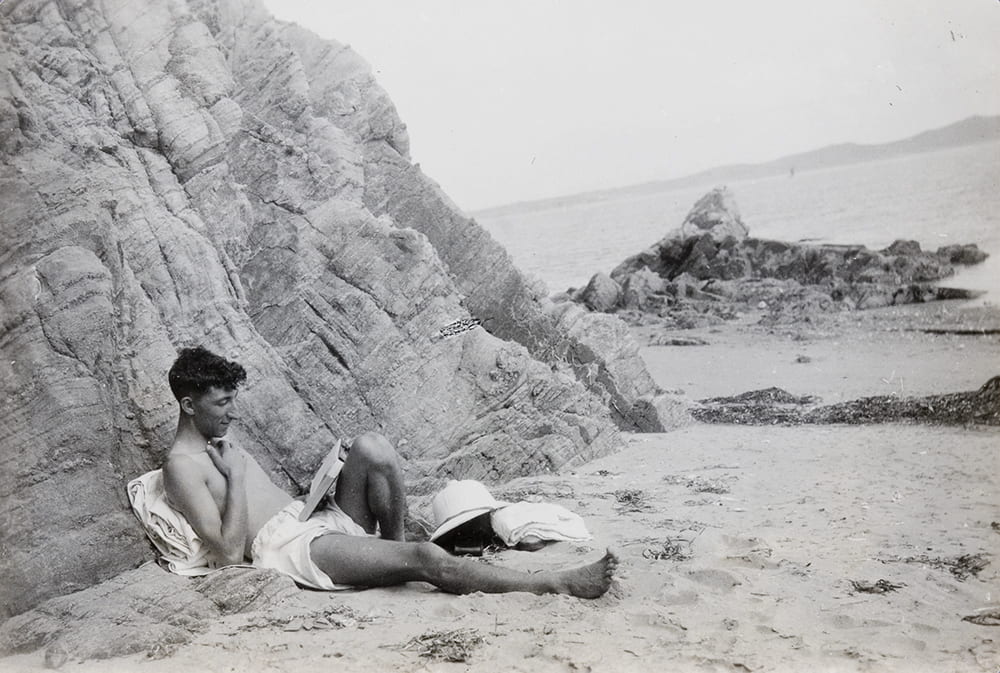

We currently know little about Hagger other than he was an Electrical Artificer in the Royal Navy. His job involved the installation and maintenance of electrical systems, including in generators and motors, on ships. He almost certainly served on the China Station aboard H.M.S. Medway, the first purpose-built large submarine depot ship built for the Royal Navy.[1] An album of photographs inscribed with his name ‘F. HAGGER, E.A.’ [E.A.=Electrical Artificer] was donated to the Historical Photographs of China a few years ago, but even then the connection with Hagger himself had been lost. Although some of the photographs in the album appear to be duplicates of images found elsewhere, many seem to have been taken by Hagger himself – or perhaps by someone close to him. The album is thoroughly captioned, and the HPC team was able to identify Hagger from some of the indications provided in the captions. He appears in several photographs, either in individual portraits – in uniform, in civilian clothes or with little clothes – or in group shots with other Royal Navy personnel.

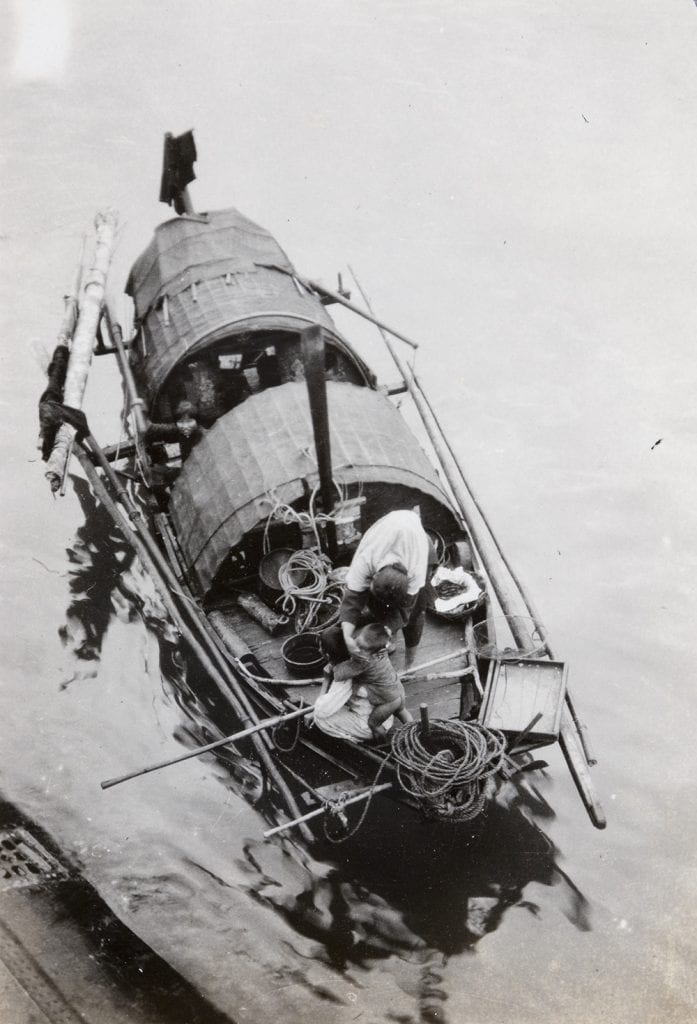

Whilst photograph albums of China coast Navy servicemen are not uncommon, the Hagger collection is impressive for the quality and variety of images. It is a rich holding for historians interested in China’s social, economic, and international history. Those working on urban and rural life in Republican China, the British military presence in the country, everyday life in the treaty ports, Hong Kong history, and maritime history (there are several photographs taken at sea and a few portraying the people who worked and lived on boats) will likely find images in this collection of interest.

The collection offers a visual record of the human and material dimensions of the routine exercise of British naval power at a period of transition when other competitors, notably Japan, were in the ascendancy. Hagger’s tour in China took place in 1932-33, at the height of the Manchurian Crisis and in the aftermath of the Shanghai War of 1932, key events in the origins of the Second World War in East Asia.[2] A state of tension was very much in the order of the day. During a visit to Japan in 1933, H.M.S. Medway was reported to ‘have been observing photographing the fortified area while traversing the Moji Straits’ by the Moji water police, an allegation denied by the Royal Navy Commander-in-Chief of the China Station, Admiral Sir Frederic Charles Dreyer (1878-1956).[3] The suspicion was not unfounded, though. According to Antony Best, the Medway was indeed being used to ‘gather information on Japanese consular, military, and mandated islands traffic’ as part of a three-month watch on Japanese wireless transmissions activities in East Asia that had been planned by the Naval Intelligence Directorate and the Government Code and Cipher School.[4]

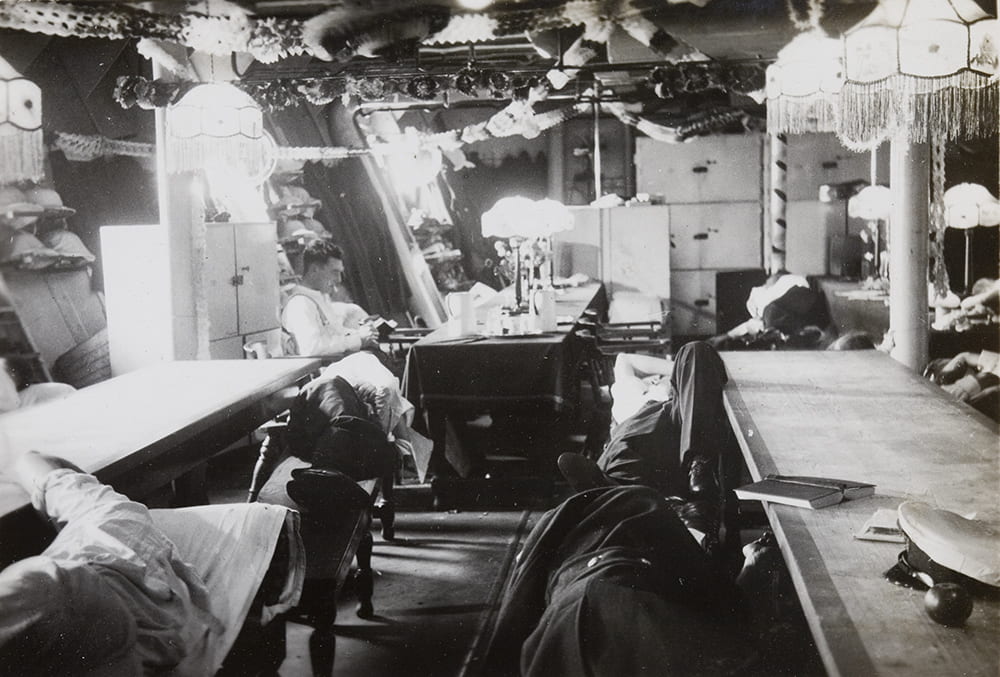

The Hagger album is also a treasure trove for those interested in gender history. Scholars of masculinities would find here plenty of inspiration: there’s a variety of depictions of male bodies, portraits of homosociality and spaces of masculine leisure and consumption (including a before-and-after sequence of a New Year’s party onboard), and examples of photographic imperial and male gaze, as well as racialised categorisation – an album page on ‘types’ of Japanese women is an illustrative example of that.

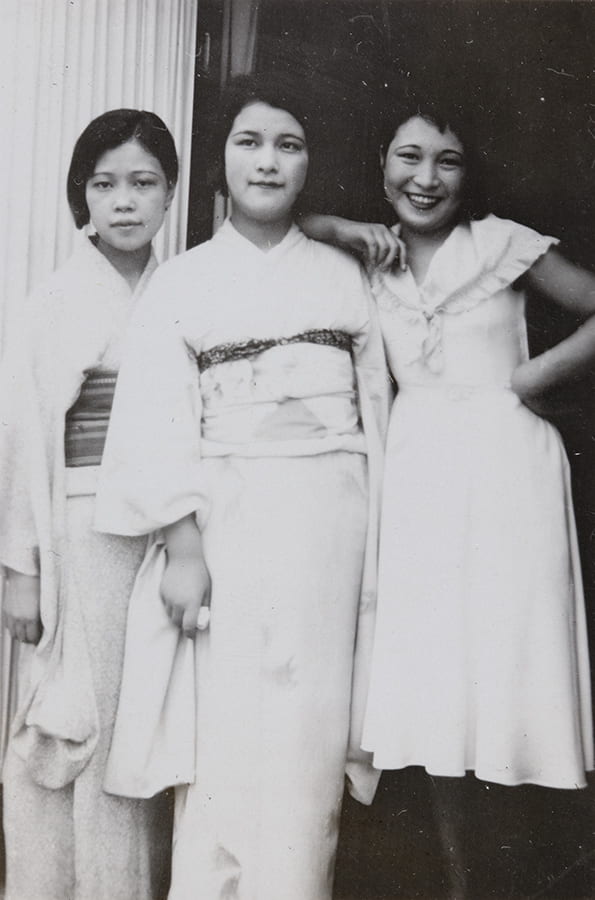

Although images of male camaraderie abound, the collection also holds very interesting images of women, especially outside shots of women at work – such as one of women road members in Hong Kong – or simply walking on the street. If 1930s China is often associated with the much-debated ‘new women’, Hagger’s photographs provide, intentionally or not, a testimony of the visibility and confident deportment of women in Chinese streets. Two photographs of ‘café girls’, seemingly photographed in Japan, also provide an interesting prompt to reflect on the transnationality of ‘modern girl’ archetypes.[5]

One of two photographs in the album, captioned ‘Café Girls’, most probably taken in Japan. HPC ref: FH01-097.

Images of bustling city life are aplenty in this collection, capturing fascinating details of the many people, businesses, and means of transport that dotted everyday activities in mainland China and Hong Kong in the 1930s. Some carefully framed images offer postcard-like distant views over the urban landscape, such as a serene shot of the Peak Tram or an impressive view over Qianmen street in Beijing.

Other photographs, taken at street level, show random shots of daily activities such as eating or chatting. The Hong Kong photographs offer quite a few gems: a side view of a fruit stall in front of a wall full of advertisements with a man eating, standing nearby, a moment of contrasts in a busy Des Voeux Road, with a barefoot girl standing on one side of the road while pedestrians, cars and rickshaws rush on the other side, or a seamstress with bound feet concentrated on mending clothes while a passer-by glances at the photographer.

One of my favourites, probably taken in Weihai, depicts a neighbourhood ally where women, children and what appear to be itinerant food sellers congregate. It was photographed from under an archway – a curious suggestion of the photographer’s position: an outsider looking in, from a distance.

Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, Xiamen, Guangzhou, Yantai, Weihai, and other China coast locales can be found in the extensive Hagger collection. Its photographs celebrate the opportunities offered to male agents of empire, but also offer fleeting glimpses of the everyday pleasures and pains of urban China during the ‘Nanjing decade’. You can browse the whole collection here and will no doubt find something interesting.

If you have information on F. Hagger or the 1932-33 China Coast tour of H.M.S. Medway please get in touch with the Historical Photographs of China Project.

[1] The ship was launched in 1928 and was torpedoed and sunk in the Mediterranean in 1942.

[2] About the latter, see Donald A. Jordan, China’s Trial by Fire: The Shanghai War of 1932 (Ann Arbor, 2001).

[3] ‘Admiral Dreyer Denies Medway Took Pictures of Nippon Forts’, The China Press, 29 September 1933, p. 1.

[4] Antony Best, British Intelligence and the Japanese Challenge in Asia, 1914-1941 (Basingstoke, 2002), p. 109.

[5] On this topic see: Alys Eve Weinbaum et al (eds), The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (Durham, NC, 2008)