There are several photographs of disasters, including some of shipwrecks, on the Historical Photographs of China site. A collection we are in the midst of readying for publication includes several that show the aftermath of the disaster that befell the S.S. Chusan, a China Navigation Company (CNCo) steamer wrecked near Weihaiwei (now Weihai) in early October 1932. This series of photographs comes from the F. Hagger Collection (about which more soon). We can relate them to other images on HPC, such as this one below, taken by the CNCo Chairman, Warren Swire, and with other materials.

Built in Greenock, Scotland in 1914 by Scotts Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. – the Scotts had intertwined interests with Swire – the Chusan was commissioned by CNCo, one of the associated companies owned or managed by John Swire & Sons in London. In China, CNCo was managed by the firm’s subsidiary, Butterfield & Swire. On the evening of 2-3 October 1932, while en route to Shanghai from Yantai (Chefoo), the Chusan ran aground, wedging on rocks of an outer island near Half Moon Bay.[1] Maritime accidents in China’s coastal waters were rarer by 1932 than they had been in the nineteenth century, when the Chinese Maritime Customs Service was still developing its lighthouse network, but they still occurred.

News reports of the time are not very clear as to the exact cause of the accident, but it seems likely the Chusan ran aground after hitting a reef. Its Captain, George Alfred Evans, a twelve-year veteran with the firm, was immediately dismissed, suggesting that he was found to be at fault; the Chief Officer was promoted. The North China Herald had reported that ‘the spot upon which the vessel ran aground is probably that known as the “Pinnacle”, which has on its crest a lime-washed piled of stones […],’ which suggests the area’s risks were not unknown.[2]

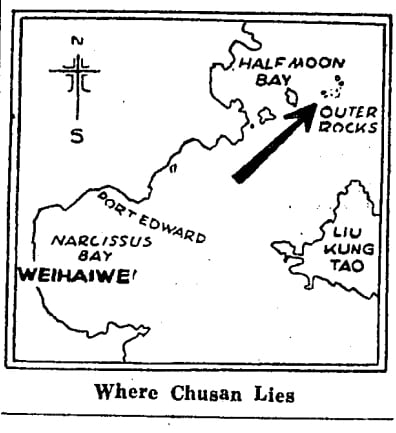

Map pointing the location where the Chusan ran aground, The North China Herald, 12 October 1932.

More than a hundred passengers and crew, most of them Chinese, were on board the Chusan when the accident happened. Assistance was provided by the British Royal Navy warships HMS Kent and HMS Medway and it is thought that someone from one of these ships, or possibly F. Hagger himself, photographed the events. These warships picked up the Chusan’s S.O.S. signals and came to rescue the passengers. They were taken to Weihaiwei and later transferred on the steamship Shuntien to Shanghai, arriving there on 6 October.[3] After saving the passengers, attention turned to recovering the cargo onboard. About one hundred packages were reported saved.[4] The crew was taken off the ship on Monday 4 October and, like the passengers was first moved to Weihaiwei and then moved to Shanghai onboard the steamer Tungchow. Like the S. S. Chusan, the S.S. Shuntien and the S.S. Tungchow were CNCo ships built by Scotts. The two would be out of operation in the following years.

The vessels involved in the salvaging operation attest to the internationalisation of China’s shipping in the early twentieth century – a period of often-competing but occasionally collaborating foreign, commercial, and nationalist interests. According to The North China Herald, apart from the two British naval vessels, the Royal Navy tug St Breock was sent ‘with divers and carpenters with hawsers, timber and other needed appliances to assist in salvage operations’. The Japanese ships Dairen Maru and Yusho Maru were sent from Dalian (Dairen) – in Japanese-occupied Manchuria – and Moji, respectively, to assist the Chusan. Both the Herald and The China Press reported that ‘Japanese tugs with almost superhuman effort have managed to manoeuvre a sampan alongside the outer island and rescue the remainder of the Chusan’s crew and one officer, totalling about 17 persons’.[5] While these Japanese ships assisted the Chusan, Sino-Japanese tensions brewed elsewhere. The ship’s intended destination, Shanghai, had seen military clashes in the early months of 1932. Interestingly, one of the first reports of the steamer’s ordeal appeared in the same front page of The China Press whose headline celebrated: ‘Lytton Report Recognizes China Sovereignty,’ a major development in the Manchurian Crisis which would eventually lead to Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933.[6] The fragile peace of the interwar years had started to go under, much like the Chusan.

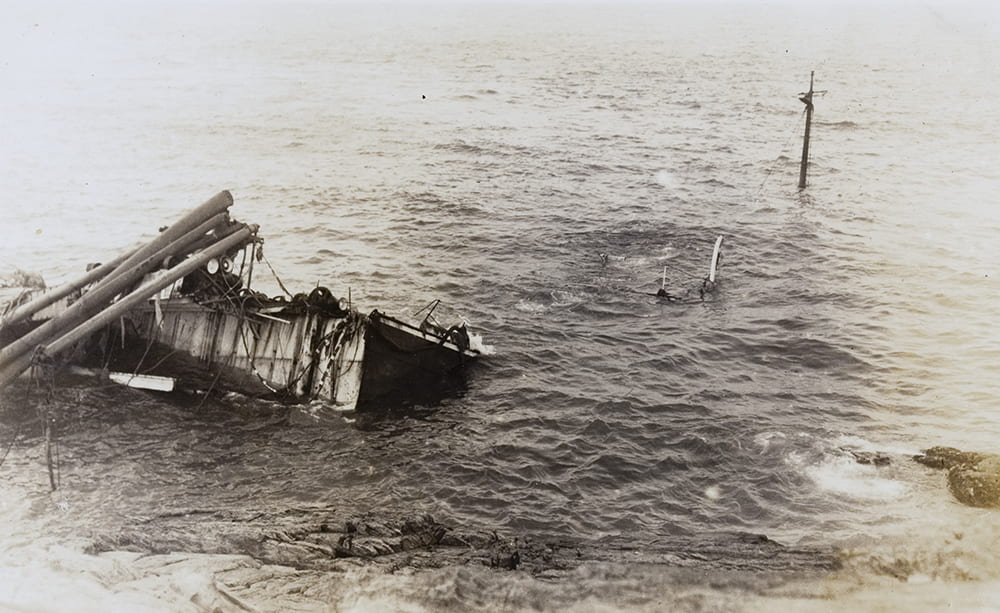

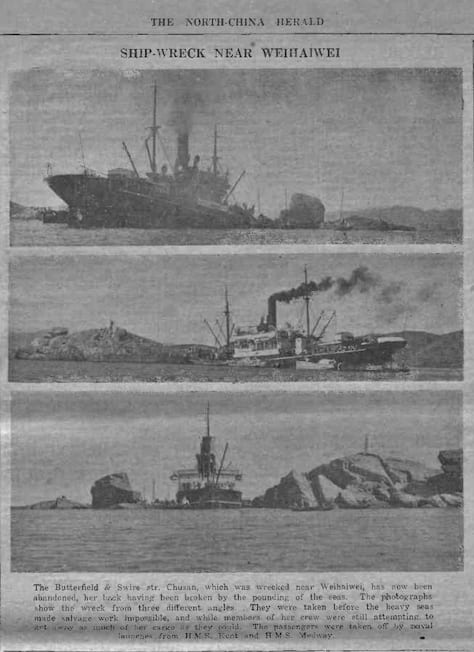

Bad weather made the salvaging operations difficult. By 4 October ‘the fore-part of the ship had been broken off by the force of waves’ and the deck was already ‘partly submerged’.[7] The Chusan was reported ‘abandoned as a total loss’ a few days later.[8] The Herald published a sequence of three photographs showing the gradual sinking of the vessel on its edition of 19 October.[9]

‘Ship-wreck near Weihaihei’, The North China Herald, 19 October 1932.

The Hagger collection includes four other images, from different angles, of the salvaging operations, which offer an impressive closer look at the different phases of the ship’s sinking – the last image, taken three days after the first, shows only a few remaining parts still above water. Historians of maritime history may find them of interest – and those wanting to recreate similar events in historical fiction have here a set of images captured on site for their reference.

When I first saw it, the sequence caught my attention as it had a certain cinematic flair to it: a step-by-step account of a ship going down, from the first impressions in which a good deal of the vessel remains above water to a final shot in which only small reminders of its physical presence are visible, most of it having been swallowed by the waters. Together, the photos tell a dramatic story. After searching for some information on the event, I realised that what the photographs do not depict is arguably even more impressive. None of them shows (at least not up close) the ship’s passengers who, unlike the ship, all survived. Other potentially interesting details are also left to the imagination of the 2020 reader of 1932 news reports: the divers who were amongst the first sent to the scene, the removal of a good deal of the cargo, the several ships involved in the rescue operations… these are largely off frame here. Perhaps someone else’s camera registered different images at the time and they now rest in a private album or archives storage somewhere in the world?

Perhaps because after the accident the association with the name might not be positive, CNCo did not name any of its new builds Chusan. Chairman J.K. Swire would still register annoyance in 1948, however, when he heard that P&O was planing to use the name for a new liner it had commissioned for the UK-East Asia route. Nonetheless, P&O, which had already owned two vessels with the name, took delivery of its third SS Chusan in June 1950. For more on the history of John Swire & Sons and its China interests, including its maritime operations, see the recently published China Bound: John Swire & Sons and Its World, 1916-1980 by Robert Bickers.

[1] ‘Str. Chusan goes aground’, The North China Herald, 5 Oct. 1932, p. 15.

[2] Ibid.

[3] ‘Wrecked vessel sinks’, The North China Herald, 12 Oct. 1932, p. 50.

[4] ‘Str. Chusan goes aground’, p. 15.

[5] Ibid.; ‘Last of Crew of Chusan Are Rescued’, The China Press, 5 Oct. 1932, p. 7.

[6] ‘Chusan Grounds Off Weihaiwei; All Saved’, The China Press, 3 Oct. 1932, p. 1.

[7] ‘Wrecked vessel sinks’, p. 50.

[8] ‘Chusan Now Regarded As Complete Loss’, The China Press, 9 Oct. 1932, p.3.

[9] ‘Ship-wreck near Weihaihei’, The North China Herald, 19 Oct. 1932, p. 91.