Adam Brookes is the author of Fragile Cargo: China’s Wartime Race to Save the Treasures of the Forbidden City, published in September 2022 by Chatto & Windus, London. He was for many years a journalist for BBC News, serving as Jakarta Correspondent, Beijing Correspondent, and Washington Correspondent.

China’s hapless last emperor, Pu Yi, vacated the Forbidden City at gunpoint in November, 1924. Less than a year later, the Forbidden City became the Palace Museum and opened its doors to Peking’s public. Rapturous crowds came to wander the halls and courtyards that had been home to the emperors of the Ming and Qing empires, and to gaze upon the magnificent imperial art collections for the first time.

For a few short years, the Palace Museum conserved and exhibited the million art objects and texts in its care, and came as close as it could to flourishing. Its finances were permanently shaky and its leadership faced criticism, envy and accusations of corruption, but it grew into one of the principal cultural institutions of the young Republic of China. The objects on display underwent a transfiguration: where once they had constituted the private, hidden treasure of emperors, now they stood as ‘national’ treasures, property of the young nation state and evidence of a ‘national’ history and patrimony.

By the early 1930s, however, the Palace Museum’s leadership fretted at the threat posed by Japan’s military incursions into China’s territory. Japan’s occupation of Manchuria in 1931 followed by the bombing of Shanghai by Japanese naval aircraft in 1932 gave rise to the terrifying notion that Peking, too, could be bombed from the air, that Japanese troops might occupy and loot the city of its treasures. The museum’s board of directors came to a drastic realisation: the imperial collections would have to be evacuated from Peking. The museum’s curators began to pack..

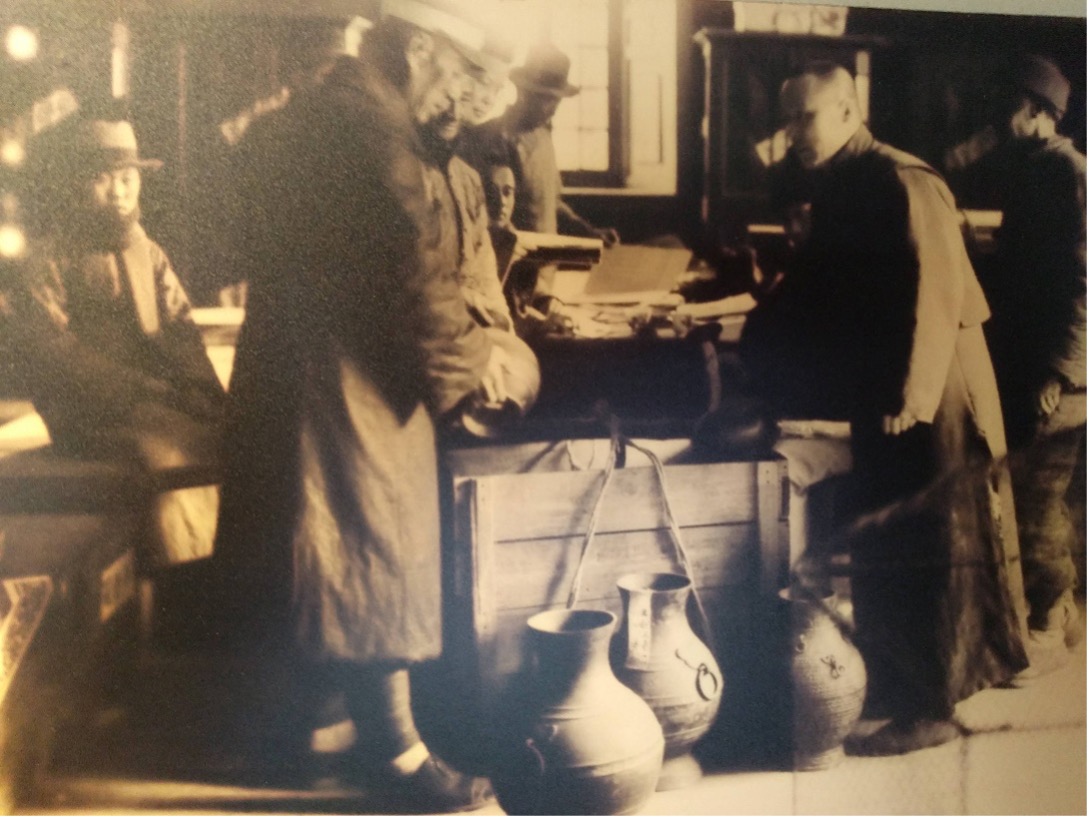

Fig. 1. Packing artefacts for evacuation from the Forbidden City, 1932. Photographer unknown.

The rarest, most irreplaceable pieces were packed by the curators in wooden cases, wrapped in cotton wadding and hemp cord to keep them separated and immobile. The photograph above is one of a very few known images of the packing process. The wooden case was one of nearly twenty thousand that would be packed, inventoried and labelled in 1932 and 1933, and evacuated from Peking. The curators, wearing long robes against the cold and the fedoras fashionable at the time, along with a uniformed soldier, are preparing to pack bronze wine jars that date from the Han period. Those same jars are today on display at the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. ‘Zhong’ wine vessel, Western Han period, c. 1st-3rd century BCE, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

The curators packed 28,000 pieces of porcelain, more than 8,000 paintings and a similar number of objects worked in jade. They packed ivories and jewellery, swords, libraries, archives, clocks and tapestries. In February 1933, the first of 19,557 wooden cases containing perhaps a quarter of a million objects and texts from the Forbidden City and other Peking institutions, awaited transport. Hundreds of porters hefted the cases out of the Forbidden City at night and took them by truck and cart to Ch’ienmen railway station to be loaded aboard freight cars.

Fig. 3. Packed cases awaiting transport out of Peking, February 1933.

The evacuated cases went first by train to Shanghai for storage in the French Concession, a strange choice, perhaps, given the fighting in Shanghai in 1932. The museum seems to have felt that the extraterritoriality of the foreign concessions might guarantee the collections’ safety, at least until a more permanent solution could be found. As the 1930s wore on and war engulfed China, the imperial collections, bundled and immobilised in their packing cases, traveled thousands of miles across China in search of safety. Their voyage lasted sixteen years.

At the heart of this extraordinary enterprise was Ma Heng (Fig. 4), who became acting director of the Palace Museum in 1933, and was confirmed in the post in 1934. It was a politically dangerous job; Ma’s predecessor, Yi P’ei-chi, was hounded out of the museum amid accusations of corruption and theft, and died in penury. Ma Heng was a wealthy businessman and antiquarian scholar who became a professor at Peking University. He played a significant role in the introduction of modern methods to Chinese archeology. He was a retiring, cautious figure, but enjoyed a measure of loyalty and respect among the museum’s curators.

Fig. 4. Ma Heng (1881-1955)

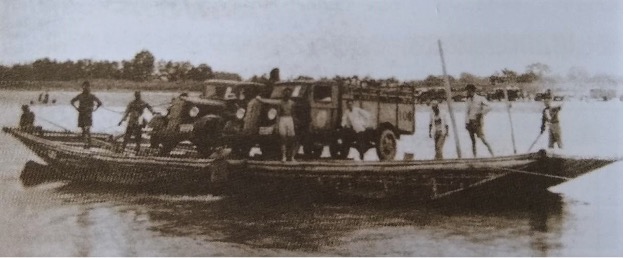

Ma Heng administered the imperial collections’ years-long, hair-raising journey to the far west of China by steamship, train and truck, raft (Fig. 5) and porter. He found storage for them in a cave in Guizhou province, and in village temples and ancestral halls in Sichuan. In these remote locations, far from the front line but still within range of Japanese bombers, the collections passed the Second World War under the care of a small band of loyal curators. Their move to the far west, into areas still controlled by the battered Republic of China, mirrored the wider migration of people, bureaucracy, industries, universities and schools from east to west in the face the Japanese advance. While the curators were preoccupied with the cases’ safety and the collections’ integrity, their effort perhaps was part of a larger effort on the part of Chiang Kai-shek’s regime to ensure that the idea of an independent, sovereign China did not die.

Fig. 5 Trucks loaded with cases containing the imperial collections cross a river on a bamboo raft, c. 1939.

In the late 1940s, as China fell back into civil war, the imperial collections remained packed in their wooden cases and were stored in Nanjing. In 1948, Chiang Kai-shek decreed that the very finest pieces of the collections would accompany him and his shattered republic on their retreat to Taiwan. Nearly three thousand cases containing imperial porcelain, masterpieces on hanging scroll and handscroll, ancient bronzes, luminescent jades, archives and encyclopaedias made the journey by ship to Keelung, and then into storage in warehouses in Taiwan’s central highlands. The imperial collections, which had resided in the Forbidden City for centuries, were now split, and have never been reunited.

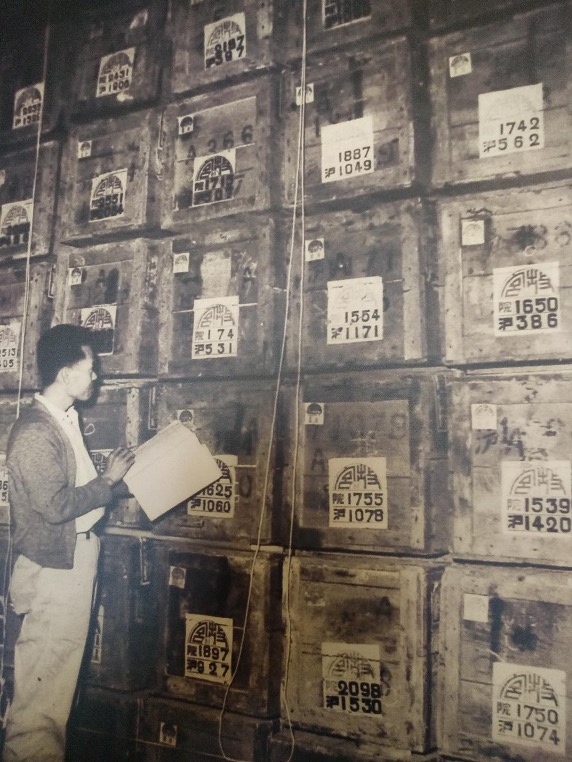

Fig. 6. Cases containing the imperial collections in storage in Taiwan, circa 1950

Figure 6 shows the cases neatly stacked in storage after arrival in Taiwan, each one’s label facing outwards for easy identification. On these particular cases, the character 院 yuan indicates that the contents originated in the Palace Museum as opposed to any other Peking institution, and the character 沪 hu indicates that the case was packed by, and contains objects from, the museum’s Antiquities Department rather than the Library or Archives. The numbers denote the cases’ place in the catalogues, and from them the curators would have been able to deduce the exact contents.

Today, the imperial collections remain divided between museums in Taiwan and in the People’s Republic of China. They continue to carry with them a certain political charge. For some, they are evidence of the greatness of ‘Chinese civilization’; others view them as symbolic of a ‘divided China’ yearning for wholeness once more. Some in Taiwan see them as part of an outdated attempt to impose an alien culture, and wish them gone. Have the imperial collections of China finally reached their resting places? It may be too soon to say.