A recent approach to HPC revealed a treasure trove of material relating to life in the British Legation, Peking, in the 1870s and early 1880s, but, as Dr Andrew Hillier explains, making sense of the photographs can be a challenge.

We keep up our music here …. Every Saturday I have a musical dinner party, Mrs Pirkis, Scherzer, Lyall (violin), Van Aalst (flute), + self … The first three are fine performers … [1]

So wrote the Inspector-General of Customs, Robert Hart, to his subordinate, Harry Hillier, but, until recently, little seemed to be known about ‘Mrs Pirkis’ or her husband, Albert, save that she was, as Hart said, ‘a fine performer’ and that he had served as the Accountant to the British Legation in Peking from 1870 to 1885.[2] However, just over a year ago, a family descendant approached HPC with a treasure trove of material relating to the Pirkis’s years in Peking – photographs, letters and, perhaps most fascinating of all, paintings, both oil and water-colours. From this, it soon became clear that Elizabeth (Bessie) Levesque Pirkis was truly a Renaissance woman in this intensely masculine world.[3] But if the letters and paintings are to some extent self-explanatory, the photographs present more of a challenge, given that there are several hundred of them and many are without captions. This is not unusual with this sort of ‘shoebox-collection’, a large number of which have been generously deposited with Historical Photographs of China for digitising over the years.[4] Whilst placing a single photograph on-line can trigger unexpected responses and leads, it can be more difficult to make sense of a large Collection of such images.[5] However, although we must avoid ‘wrenching them out of their frames and context’, in this two-part blog, I want to explore not only how the images ‘once lived as objects’ but also what, taken together and filling in the gaps where I can, they may tell us about legation life at this time. [6]

None of the photographs, it seems, were taken by Bessie or Albert. This is not surprising given that the hand-held Kodak was yet to arrive and there was no possibility of taking quick snaps.[7] However, there were already professional and semi-professional photographers in Peking and the Pirkis’s compiled an album containing a large number of pictures of the city and its surroundings. Whilst these are of interest, it is the loose photographs, collected piecemeal during their time in Peking, on which I want to focus. The collection must have started on Bessie’s side of the family because a number predate her arrival. We can begin with one which was taken before her wedding but which she may well have given or sent to Albert before or at the time of their engagement – see figure 1.

Figure 1: Bessie L’Evesque. It is captioned ‘Heartease’ on its reverse, the common name for a wild pansy and the name by which she was usually called by her family and, perhaps, also by Albert, and the flower which she is wearing. HPC PF-s0037.

Originally Huguenots, Bessie’s family, the Levesques, or, as she liked to style herself, L’Evesque, had established themselves as ‘piano-forte makers’ and dealers in musical scores in East London. It is not clear when or how Bessie and Albert met – she was thirty-three and, unusually for the time, he was four years younger – but they may have been related through Bessie’s step-father, William, whose surname was also Edmeades. A piano-maker himself, for some time, he seems to have been in business with Bessie’s brother, Josiah. The engagement must have been sealed by an exchange of letters since the wedding took place in Shoreditch, London on 29 June 1869, soon after Albert’s return from Hong Kong, where he was serving in the Auditor-General’s Department. [8] Setting off back to China ten months later, he and Bessie travelled through France and stayed in Paris, where they had their portrait, or ‘likeness’, as it was called, done before continuing on by train to Marseilles – see figure 2.

Figure 2: Albert and Bessie Pirkis. Photograph taken in a Paris studio in 1870 when they were on their way to Hong Kong. HPC PF-s0046.

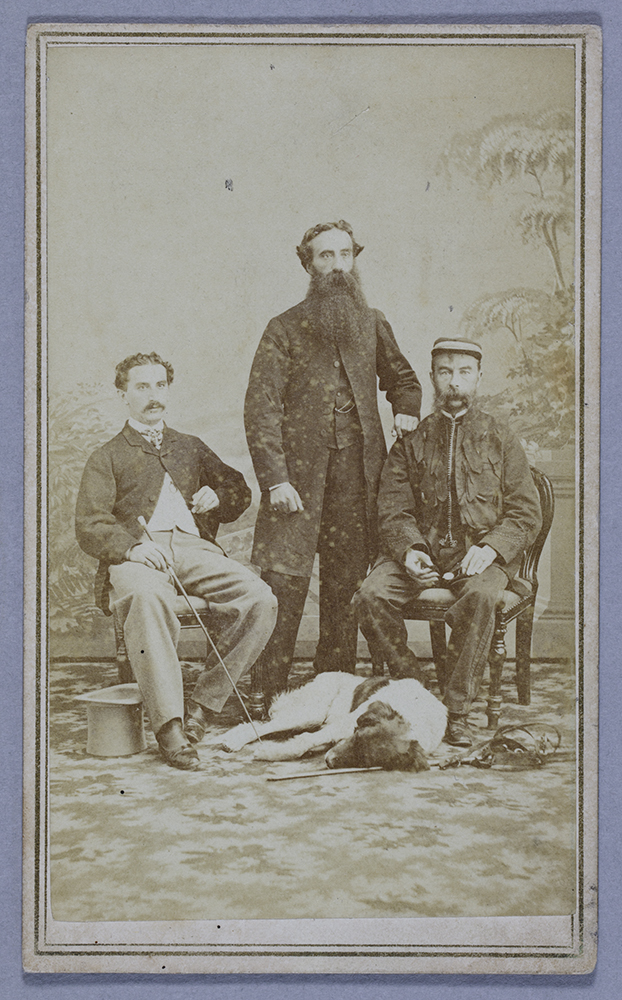

From there, they caught the Messageries Maritimes steamer. The youngest of four sons, Albert had first arrived in Hong Kong in 1862, following in the wake of his eldest brother, George Ignatius Pirkis, who had joined the Army Commissariat in 1850 and had been posted to the colony two years later. After taking charge of the arsenal during the Second Opium War and later serving with the Ever Victorious Army, he returned to Hong Kong and would remain stationed there until 1875.[9] In 1866, the second eldest brother, Daniel, had followed George and Albert to take up an appointment as Consular Chaplain in the treaty port of Kiukiang (Jiujiang) [10] – see the photograph at figure 3. Formally posed with George wearing the civilian uniform issued to Commissar staff, Daniel sporting a magnificent beard, which had recently become fashionable, and Albert looking self-important with cane and top hat, copies must surely have been sent home to the family in England for distribution to friends and relations.

Figure 3: Albert, Daniel and George Ignatius Pirkis. Undated but captioned in Albert’s writing, ‘The three China brothers…Dad, Dan & Al and my faithful dog, Hep’. HPC PF-s0007.

Soon after their arrival in Hong Kong, Albert was informed that the Audit Office had been transferred to Peking and in the autumn he and Bessie set off again, making their way by steamer to Shanghai and then on to Tientsin (Tianjin) from where they went by river-boat and then mule-cart to the capital. Comprising a vast and picturesque palace with extensive grounds, the compound provided ample space for them to have their own separate accommodation.[11] It was there that Albert, as Legation Accountant, and Bessie would spend the next fifteen years.

Their arrival coincided with Thomas Wade succeeding Sir Rutherford Alcock as Minister.[12] A very different character to his predecessor, Wade was a highly accomplished Sinologue and a somewhat unworldly figure. Recently married, during his twelve years in office, although prone to irascibility, he would be reasonably easy-going in managing the legation staff, which comprised two career diplomats and a small number of consular officials. Alongside them would be a cohort of young Student Interpreters, who would spend a rigorous two years learning Chinese with a ‘native’ teacher, culminating in an examination by the Chinese Secretary – at that time, the brilliant but unforgiving W.S. Frederick Mayers.

As is clear from the photograph at figure 4, the Interpreters could enjoy a much more relaxed relationship with Albert Pirkis, since they were not accountable to him.[13] We see him with his close friend, Dr Stephen Bushell, the Legation’s medical adviser, surrounded by students. As usual, dogs are in evidence and the tone is informal, if self-conscious, with the students’ poses ranging from languid to earnest.

Figure 4: Student Interpreters with Albert Pirkis and Dr Stephen Bushell. Back row (standing, left to right): J.D. Crawford and W.S. Ayrton. Middle row (sitting, left to right): Walter C. Hillier, later to be Chinese Secretary, W.D. Spence, Albert Edmeades Pirkis, with his hat on his lap, Dr Stephen Wootton Bushell, (with a Pekingese on his lap), T. L. Bullock (also with a blurry dog on his lap), W. H. Young. Front row: a large dog called Jack; R. W. Mansfield, with his hat on his feet, W. R. Carles, with another Pekinese dog. Ayrton, Bullock, Carles, Hillier and Mansfield would all become Consuls. Albert’s beard has grown considerably since his arrival. 1870/1871. HPC, Hi-s022.[14]

This atmosphere owed much to Wade’s wife, Amelia. The eighth of twelve children born to the famous astronomer, Sir John Herschel and his wife, Margaret, Amelia was said to be ‘everything that the wife of an official in the East should be, thoroughly and fundamentally British, cheery, kind, intelligent, a woman who never made a mistake’.[16] In just over three years of marriage, she had borne Wade three children and would bear him three more over the next three years. [17]

Figure 5: Amelia Wade. Undated, HPC PF-s0721.

To add to this familial setting, Frederick Mayers, the Chinese Secretary, and his wife, Jeannie (née McKenna) – see figure 6 – had two young boys under the age of five.

Figure 6: Jeannie Mayers. Undated. HPC PF-s0209.

Following Bessie’s arrival, there will most probably have been an early exchange of the cartes de visite which we have seen at figures 1,2, 5 and 6. Although this sometimes occurred as a matter of formality, they were mainly used as ‘tokens of affection’ and a way of sharing images not dissimilar to today’s Facebook or Instagram. Although the above were all taken in England, a stock will have been retained for the purposes of later circulation. [18] There is a large number of such cartes in the collection and, if many of the sitters cannot be identified, we can be reasonably sure that many relate to this time.[19] Settling into this world, Bessie and Albert had two children, the first, Amy, arriving on 1 January 1872, and Albert George (always known as Georgie), three years later.

Given that portraits were generally executed in a studio, there are very few photographs of children at a young age and so the one we have at figure 7 is particularly unusual, being taken within the Legation.

Figure 7: Amy and Georgie Pirkis with an unidentified child on the left-hand side and a Chinese man, probably a servant, and three dogs. 1878? HPC PF-s0624.

Although the children appear to be dressed for the occasion, the setting is reasonably informal and can be contrasted with the carte which the Revd Burdon must have presented to Bessie showing himself and his family in a much less relaxed pose.

Figure 8: Revd John Burdon with his wife, Phoebe (née Esther) and their two children. HPC PF-s0179.

A fervent Sinophile, Burdon had spent ten years as a missionary teacher at the Tongwen guan, originally established as a Qing government language school in Beijing in 1862, before leaving in 1873 to take up his appointment as the Bishop of Hong Kong. A close friend of Bessie and Albert, strong religious beliefs will have been an important bond between them.

The picture of Amy and Georgie will almost certainly have been sent to friends and relations at home. That there are no surviving photographs of Albert and Bessie with the two children at this time may well have been because of the difficulty of obtaining formal studio pictures in Peking. However, the photograph at figure 9, taken a little later at one of Hart’s parties, conveys an atmosphere in which children could be both seen and heard, with their being given cart-rides under the careful attention of a Chinese servant:

Figure 9: Group of forty men, women and children, taken in the grounds of Robert Hart’s house. Amy is standing on the left of the four girls wearing a pale dress and hat, Georgie is on the far right, beside the cart. The other children have not been identified. Hart (on the right-hand-side in bowler hat) had a particular affection for Amy, to whom he wrote after the family left Peking, and Georgie, to whom he gave a valuable violin. Undated but probably c. 1880. Taken just before the arrival of the hand-held Kodak, all such photographs had to be formally posed. HPC PF-s0641. Compare with Ca02-100, possibly a more formal occasion, in which there is only one child.

Pidgin English was not spoken in Peking and, spending much time in the care of their amahs, the Legation children all learned some Chinese and, save when with their parents, ‘never spoke any other language among themselves or with anyone else till they were much bigger’. Visiting the Legation, Li Hongzhang (one of the Qing’s most powerful and intimidating officials) delighted to watch them and ‘listen to their fluent Chinese talk’. [20] However, this congenial atmosphere was shattered when, in March 1875, news arrived of the murder of Augustus Margary, a young consular official, whom Bessie and Albert will have known when they first arrived in Peking. Threatening Li with war if his demands were not met, Wade packed his wife and six children off to England in late April 1875, and, whilst Amelia would return, the children would not do so. However, he failed to persuade the other Legation wives to leave for Chefoo (Yantai).[21]

Although Sino-British relations would be extremely tense over the next eighteen months, this does not seem to have unduly affected the pace of legation life. Recently married and appointed First Secretary, Hugh Fraser had arrived in 1874 with his attractive and sophisticated wife, Lady Mary Crawford Fraser. The first of their two children were born the following year, a time when, as she recalled, Peking ‘was enduring the hottest summer on record’. [22]

Figure 10: Lady Mary Crawford Fraser. Taken in Rome, probably shortly before her marriage to Hugh Fraser, where he was Diplomatic Secretary in the British Embassy, before taking up his appointment in Peking. HPC PF-s0254.

With Amy aged four and Georgie just one, it will have been a worrying time for Bessie. The only saving was the complex of Buddhist Temples in the Western Hills, known as Badachu, where Legation wives and children could get away from the heat, smell and noise of the city. Accompanied by the Student Interpreters, for whom studying in such conditions was unthinkable, they would be joined at week-ends by their husbands. [23]

With so many babies arriving and no trained mid-wife on hand, Stephen Bushell will have been responsible for superintending the births. Having then taken long leave, he had returned with his recently-married wife, Florence (née Mathews),‘a typical English girl’, who, according to Mary Fraser, was in the process of ‘making her new home an exact copy of the Sydenham villa she had left behind her’. [24] Mary’s snobbishness probably did not worry Bessie, whose taste may have been no better than Florence’s. She is not mentioned in Mary’s memoir and, on this occasion, the exchange of cartes may have been more for form’s sake – see figure 10. However, with Pirkis forming a close friendship with Bushell – they were both keen collectors of porcelain – no, doubt, Bessie and Florence had plenty of time to spend together and their cartes will certainly have been exchanged as tokens of affection – see figure 11.[25]

Figure 11: Florence Jane Bushell. Undated. HPC PF-s0091.

Some, but by no means all, of the above images have appeared elsewhere but it is their presence within a single collection, along with all the other photographs, which gives them a particular significance, showing the importance of intimate relations within the formal legation world. After seven years, Bessie had become a leading figure in that world, and, with the children growing up, she was now able to make more of her talents, as we shall see in Part 2.

Andrew Hillier’s The Alcock Album: Scenes of China Consular Life, 1843-1853, will be published by City University Press, Hong Kong, later this year. Click here for more details and updates.

[1] Letter, Hart, Inspector-General, Imperial Maritime Customs to Harry Hillier, 26 October 1883 (Private Collection).

[2] Cf. https://blogs.qub.ac.uk/specialcollections/music-making-in-the-customs-service/

[3] I am extremely grateful to Nicola Pirkis for allowing me to draw on the Pirkis Collection, which has now been digitised by HPC, and for giving me the benefit of her research on the Pirkis and Levesque families. It was a particular pleasure working with Nicola as she is a great-great-granddaughter of Bessie and Albert, and Harry Hillier, who knew Bessie well and was the recipient of the letter from Hart, was my great-grandfather.

[4] Cf. https://www.flickr.com/photos/whatsthatpicture/galleries/72157628628085879/ https://www.kulturacollective.com/exhibitions_proper/the-shoebox-collection/

[5] See, for example, It was wonderful: Lully Goon, aviatrix https://robertbickers.net/

[6] Robert Bickers, ‘The Lives and Deaths of Photographs in China’ in Christian Henriot and Wen-hsin Yeh (eds), Visualising China, 1845 -1965: Moving and Still Images in Historical Narratives (Leiden: Brill, 2012), pp.3-38, quotes at p. 3.

[7] Cf. https://visualisingchina.net/blog/2017/01/26/the-kodak-comes-to-peking/

[8] TNA FO 17/537, letter, Alcock to Auditor-General’s Department, 14 October 1868, 55, referring to Pirkis being granted one year’s leave. He did not leave Hong Kong until 9 March 1869, suggesting that Bessie took longer to accept the proposal than he anticipated or that the wedding had to be delayed for some reason. The journey will have taken about five weeks.

[9] Richmond & Twickenham Times, 12 July 1890.

[10] TNA FO 17/460, letter, Hammond to Daniel Pirkis, 28 February 1866, f.223 and following.

[11] J.E. Hoare, Embassies in the East, The Story of the British and their Embassies in China, Japan and Korea from 1859 to the Present (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 1999), pp. 21-23, HPC BL-n023.

[12] Previously, Chargé d’ Affaires, Wade formally took up his position in July 1871.

[13] For life as a Student Interpreter, see ‘Where Chineses Drive.’ English Student-Life at Peking (London: W.H. Allen, 1885), initially published anonymously, but later attributed to W.H. Wilkinson, who joined the Service in 1880 and will have known the Pirkis’s well; for a description of their house, see pp. 26-27; see also Cf. Andrew Hillier, ‘Bridging Cultures: The Forging of the China Consular Mind’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, (2019) 47, pp. 742-772 at pp. 748- 753.

[14] The same photograph is also in the Pirkis Collection, HPC PF-s1016; for legation staff, see PF-s0632 and PF-s0633.

[15] See Nick Pearce, ‘A Life in Peking: The Peabody Albums’, History of Photography, 31 (2007), pp. 276-293 and Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China: Western Photographs, 1861-1879 (London: Quaritch, 2010), p. 31-79.

[16] Mrs Hugh Fraser, A Diplomatists’ Wife in Many Lands (London: Hutchinson, 1913), II, p.153.

[17] Letters, Hart to Campbell, 1 September 1871 (25), 21 November 1872 (45), 10 February 1875 (119), John K. Fairbank, Katherine Frost Bruner, Elizabeth Macleod Matheson (eds), The I.G. in Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs, 1868-1907 (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1975).

[18] Cf. Bickers, Robert, ‘The Lives and Deaths of Photographs in China’ , pp.21-25, quote at p.24; see also https://visualisingchina.net/blog/2017/07/07/regimental-cartes-de-visite/

[19] See, especially those at HPC, PF-s0678 and PF-s0818.

[20] Fraser, A Diplomatist’s Wife in Many Lands, II, p.191.

[21] For Margary’s murder, see Robert Bickers, The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914 (London: Allen Lane, 2011), pp. 258-261 and for reaction in the Legation, Fraser, A Diplomatist’s Wife in Many Lands, II, pp. 144-149.

[22] Fraser, A Diplomatist’s Wife in Many Lands, p.153; for the Frasers, see also Pearce, ‘A Life in Peking’, History of Photography, 31 (2007), pp. 276-293.

[23] Hoare, Embassies in the East, pp. 30-31; ‘Where Chineses Drive’, pp. 197-234; see, for example, Facade of Da xiong bao dian at Fa hai si, HPC, Hv13-13.

[24] Fraser, A Diplomatist’s Wife in Many Lands, II, p.148; cf. Helen McCarthy, Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), pp. 26-7.

[25] Nick Pearce, “Collecting, Connoisseurship and Commerce: An Examination of the Life and Career of Stephen Wootton Bushell (1844–1908)”, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society. 70: 17–25.