As we approach the 105th anniversary of Armistice Day, Andrew Hillier considers the significance of the ceremony in treaty port China and for Chinese people today.

Held at the Cenotaph in Victoria Park, Tianjin (Tientsin), the Armistice Day parade was ‘the most impressive’ of the imperial celebrations to take place in the treaty port, recalled Brian Power in his memoir of his early life in China. Modelled on the service in Whitehall, London, the Consul-General (William Pollock Ker) took the place of the King alongside members of the British Municipal Council and behind them, foreign military guests in a variety of uniforms, the French in blue-grey steel helmets, Italians with bright blue sashes and gold epaulettes, Americans with wide-brimmed Stetson hats, and the Japanese with long curved swords. On the other three sides,

a company of British soldiers, sailors from HMS Hollyhock, the Volunteer Corps, members of the British Legion and the Boy Scouts were drawn up … British families, well wrapped up in furs against the cold weather, gathered behind the soldiers, while crowds of curious Chinese watched from outside the railings. [1]

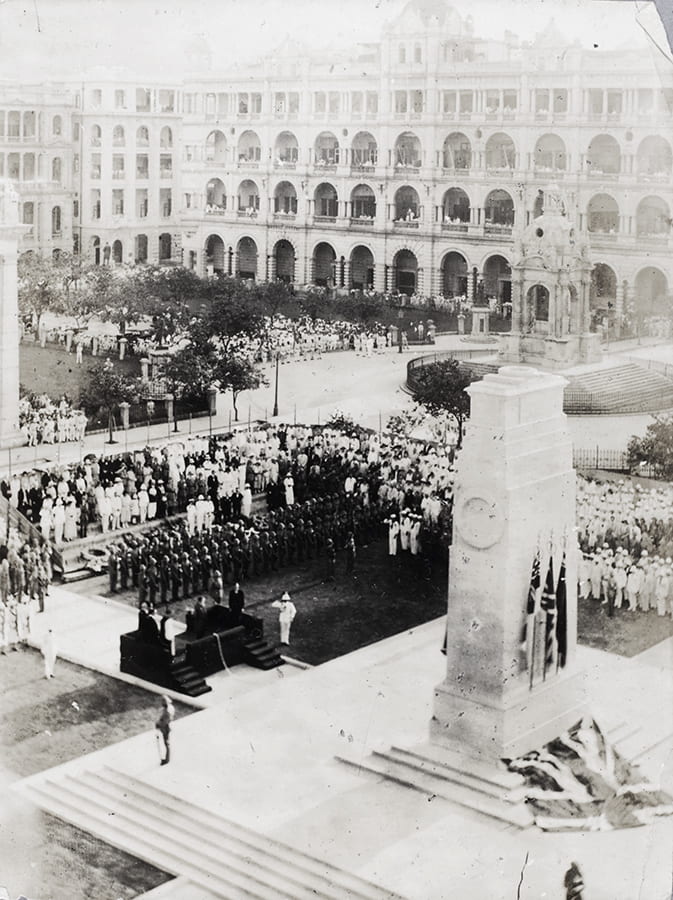

A similar ceremony took place each year in Shanghai, as we see in this image.

The previous year, a special parade had been held in the grounds of the British Consulate, Shanghai, in which the Boy Scouts and Wolf Cubs were inspected by Sir Skinner Turner, as President of the Boy Scouts Association of Shanghai, and Consul-General Sir John Pratt.[2]

Boy Scouts Parade at the British Consulate, Shanghai, on Armistice Day 1924. Left to right: Sir John Thomas Pratt (1876-1970), British Consul-General, Shanghai – Unidentified Royal Navy commander – Sir Skinner Turner (1868-1935), Chief Judge of the British Supreme Court for China from 1921 to 1927 – Sir John Fitzgerald Brenan (1883-1953), British Consul-General, Canton. Archibald Lang Collection, AL-s14.

In Hong Kong, a replica cenotaph was also erected.

Unveiling of the Cenotaph, Statue Square, Hong Kong on Empire Day, 24 May 1923. Billie Love Historical Collection, BL-s012.

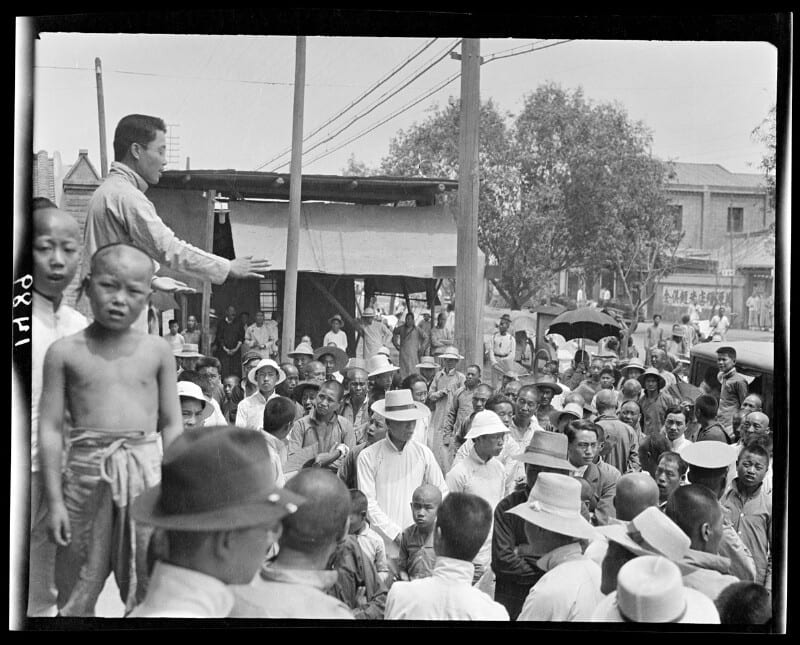

An important event in the imperial calendar, each year, the ceremony would implicitly validate the western presence in China. For the ‘crowds of curious Chinese’, however, it came with a bitter taste. As Robert Bickers says, ‘The Allies would soon start to forget that China had been on their side in the Great War’ and, by November 1919, it was clear that they were not going to honour the undertaking that, in return for providing the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC) for the Western Front, Shandong would be restored to China. Instead, Japan was allowed to occupy the province as a zone of influence. On 4 May, 1919, a mass demonstration of students took place in Peking to protest at the failure of China’s officials at Versailles to secure compliance with the wartime undertaking. What became known as the May Fourth Movement launched ‘a nationwide assault on imperialism and on China’s prevailing culture’ and its anniversary became an important event in China’s narrative of the western presence.[3]

June 3 1919, YMCA Student demonstration, Beijing. Sidney D. Gamble Photographs Collection, Duke Digital Collections.

And so, for the remainder of that presence, two ceremonies would take place each year in China, one commemorating the Allies’ victory and the ensuing Armistice, the other commemorating the failure of the Allies to honour their commitment and China’s first steps towards ending that imperial presence.

But, despite the contribution of the CLC, it went unrecognised during the Armistice ceremony. And, still today there is no memorial in Great Britain honouring the thousands of CLC workers who died, save for five white Commonwealth War Graves in Anfield Cemetery, Liverpool, where members of the CLC, who died in Liverpool in 1917 and 1918, are buried. Elsewhere, in addition to their gravestones, a number of memorials honouring the contribution of the CLC have been erected.[4] In November 2017, a plaque was unveiled in Belgium near the village of Busseboom, Poperinge. In December 2018, the British Chargé d’Affaires unveiled a memorial plaque which the British government had presented to the Qingdao Museum of the First World War.[5] And in May this year, a ceremony took place at Saint-Etienne- au-Mont Communal Cemetery marking the restoration of the Chinese memorial to the CLC.

Thanks to the efforts of Ensuring We Remember, there are now plans to erect a similar memorial in this country.[6] And, as has happened each year since 2017, this Armistice Day, a wreath honouring the contribution of the CLC will be placed at the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

Andrew Hillier, The Alcock Album: Scenes of China Consular Life will be published later this year.

*

[1] Brian Power, The Ford of Heaven: A Childhood in Tianjin, China (Oxford: Signal Books, 2005), pp.110-112.

[2] See an account of the day published in the North-China Herald, 15 November 1924, p274.

[3] Robert Bickers, Out of China, How the Chinese Ended the Era of Western Domination (London: Allen Lane, 2017), pp.1- 5 and 26-34.

[4] See, for example, the gravestones at the Chinese Cemetery, Noyelles-sur-Mer, Picardy .

[5] See also https://medium.com/@haroutjoulakian/qingdao-world-war-i-heritage-museum-c145074d1689 The government post states that there is already a commemorative memorial in London but it is unclear to what this refers.

[6] A memorial has been constructed in China but there is uncertainty where it is to be erected – see this South China Morning Post story.