Jamie Carstairs (Special Collections, University of Bristol Library) is researching the work of Charles Frederick Moore (1838-1916). In this post, Photodetective Carstairs reinvestigates a photographic cold case…

Fig. 1. A gilded bronze Buddha, with two unidentified men, British Legation, Beijing, c. 1869. A rare, hand-coloured print of a photograph by Charles Frederick Moore. Image courtesy of the Terry Bennett Collection (ref: BPEK-3).

In my mind, three golden Buddhas lined up in a row, as if in a one-armed bandit of yore; there was a laden, brain defogging pause, then “Aha! I think I have it”, a cascade of thoughts, followed by a flurry of checking and googling to confirm the hunch.

In 2013, this image (fig. 1) of a gilded bronze Buddha was shared with the Historical Photographs of China team, along with analysis which compellingly indicated that the location was the British Legation, Beijing.

Curiously, it was observed by one investigator that the pedestal was made of wood.[1] The unusual photograph raised additional questions for me – why was the ‘Laughing Buddha’ outdoors, apparently in a garden? And why were the European men posed, in seemingly proprietorial stances, beside a Chinese devotional object? All very odd. The perplexing picture was mentally added to my ‘unresolved puzzles’ pile.

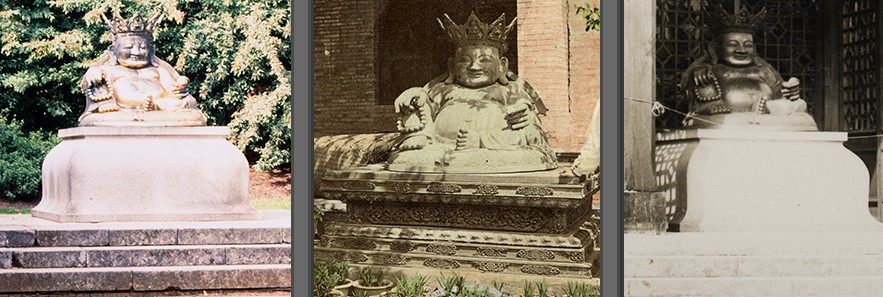

Fig. 2. This faded print of a photograph by Charles Frederick Moore, is pasted into his album at the Irish Jesuit Archive and captioned ‘Big Bell’ed God, Pekin’. Other known prints are labelled ‘The Bronze Joss Ta tu tza, Peking’ (i.e. The bronze, big-bellied god, Beijing) and ‘Bronze Idol’. Reference image courtesy of the Irish Jesuit Archive, Dublin.

Years later, the same photograph (fig. 2) was spotted in Charles Frederick Moore’s album at the Irish Jesuit Archive, Dublin, piquing further my interest in it.[2] This summer, prompted by my ‘one-armed bandit’ whim, I looked closely at an old post card (fig. 3) I’d bought on ebay, of the Buddha at Sandringham House, Norfolk, England – the country retreat belonging to King Charles – and was astonished to realise that the Sandringham Buddha was the same one as the Peking Buddha in Moore’s photograph.

The revelation led to more discoveries and is quite a story in itself. Admiral Sir Henry Keppel, Commander-in-Chief, China Station, is said to have ‘found’ or ‘purchased’ the Buddha in Peking. He had the ‘Joss’ (as Britons routinely referred to such icons at the time) spirited out of China and shipped to England aboard HMS Rodney. Keppel gave it to his friend, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), as a housewarming gift for his new house at Sandringham in Norfolk.

Fig. 3. The ‘Chinese Idol,’ at Sandringham House, Norfolk, England, c.1925. The Chinoiserie wooden ‘pagoda’ over the sculpture was put up by estate carpenters, for Edward, Prince of Wales, in the 1870s. The canopy was demolished in 1960, as the woodwork had become rotten. The Buddha was (and still is) flanked by two granite Japanese lions, also presented by Admiral Keppel.

While staying at the British Legation, Beijing, in 1869 Keppel, noted in his journal that ‘The Joss went off on Saturday’ – i.e. 22 May 1869.[3] The Rodney finally left Chinese waters on 23 September 1869, departing from Hong Kong, along with two granite Japanese lions (also to be given to the Prince), two bears, a pair of cassowaries and some pigs, and arrived at Portsmouth on 12 April 1870. The Buddha was delivered via King’s Lynn, to Sandringham House shortly afterwards.

These dates might help the identification of the men in Moore’s photograph. They have long been thought to be the great Scottish photographer John Thomson on the left, with Legation surgeon, Dr John Dudgeon, also a noteworthy figure in the history of photography in China, on the right. But, as far we know, John Thomson didn’t get to Beijing until 1871. Dr Dudgeon was resident in the city in 1869, but the man in the photograph does not look like him. Known, reliably captioned pictures of Dudgeon do not resemble the bushily bearded man on the right, whose workaday clothes do not look like those of a Victorian doctor, a member of the professional, upper middle class. So, who are the men?

Keppel recorded that whilst he was at the British Legation, he ‘went to see the Joss that the Sergeant of Minister’s Bodyguard has brought for me’, on 20 May 1869.[4] A man called Franklin was the Sergeant of the British Minister’s Bodyguard in 1869, that is, the senior Legation escort and guard.[5] It is feasible that the men with the Buddha in Moore’s photograph include Franklin and another of the guard, but I have no evidence to support this speculation. How the sculpture came to be at the British Legation also remains a mystery. If it was purchased from impoverished Buddhist priests or monks, in which temple or monastery had it been?

Fig. 4. The ‘Laughing Buddha’ (Budai) at Sandringham House, August 1934, when still housed under a ‘pagoda’ canopy. Note the good condition of the gilt. Photograph by George Plunkett (Source: http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/).

Keppel further recorded that ‘Sir Rutherford [Alcock, British Minister, Beijing] directed that it should be carefully covered with matting for fear any dévote Chinaman should take umbrage at a god being removed from the Celestial Empire.’[6] Perhaps coincidentally, a roll of matting can be seen in the background of Moore’s photograph. One can speculate that the matting had just been taken off the sculpture for the photographer. The Buddha and Keppel travelled by waterways from Beijng to Tianjin, accompanied by a Chinese Official. Keppel noted: ‘The mandarin who accompanied us was anxious to know if I should burn incense before it when I got home. I have no doubt he thought I was a convert to Buddhism.’[7]

Fig. 5. Sir Henry Keppel, known as ‘The Little Admiral’, with his friend, Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), in 1894. The Prince was instrumental in Keppel procuring the command of the Royal Navy fleet in China in 1866. Photograph as reproduced in ‘Memoir of Sir Henry Keppel. C.G.B., Admiral of the Fleet’ by Sir Algernon West (1905).

Keppel added that he ‘sent a photograph of it [the Buddha] to General Knollys’, who was Treasurer and Comptroller of the Household of the Prince of Wales.[8] This was most likely the photograph by Moore. It is reasonable to deduce that Keppel had commissioned Moore to take the photograph, as a record, and in order to send to Sir Francis Knollys, as Knollys was involved in planning the gardens at Sandringham House. Unfortunately Keppel’s covering correspondence with Knollys and this particular print of Moore’s photograph are unlikely to have survived, as Knollys destroyed many of his papers relating to the Prince of Wales, for fear of scandal.

The ‘Laughing Buddha’ (Budai) is an incarnation of the Maitreya in a specific guise. The big belly of the Bodhisattva represents ‘a number of Chinese life-ideals’ – a genial, prosperous, well-fed, spiritually contented being, happy in his own body and surrounded by his gamboling children.[9] For the Royals, the ‘Chinese Joss’ is said to have been referred to by the affectionate nickname ‘John Chinaman’ or ‘Mr Chinaman’.[10] James Pope-Hennessy wrote that the Princesses Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) and Margaret, when children, called him ‘Laughy’ or ‘Goddy’.[11] Their mother wrote in a letter to King George V in 1924 that she hoped that ‘the little yellow Chinaman is bringing the luck he is supposed to’.[12]

Fig. 6. The Sandringham Buddha’s big toe, the gilt rubbed off for luck, or in veneration, by visitors, who also nowadays leave coins in his lap. Photograph by Jamie Carstairs. A memory of taking photographs of the Buddha in 1994 surfaced this summer, along with figs. 1 and 3, to connect the Sandringham Buddha with the Beijing Buddha photographed by Charles Frederick Moore.

As for visitors to Sandringham House, the Buddha is something of a dislocated, gaudy curiosity. Helen Cathcart described the divinity as ‘blandly-smiling’; James Pope-Hennessy likened his ‘lascivious smirk’ to the face of the Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev; Mike Biles found its ‘unpleasant little smirk’ ‘slightly creepy’; to Elle Seymour, the sculpture is a ‘happy chappy’.[13]

The gilded bronze Maitreya Bodhisattva, now bereft of its ‘pagoda’ shelter, still graces the gardens of Sandringham House, fully exposed to the elements, stained, scratched, and gently corroding. The artwork is recorded as having been made in 1690 by Yen-Ling-Yin and Ling-Sun, Buddhist priests/foundry workers.[14] The representation of the deity was found to have many Chinese coins inside it, presumed to be the offerings of the faithful at some long-forgotten place of worship.[15] Whether one considers the seventeenth century Laughing Buddha as an ‘extraordinarily fine’ historical work of art, or as a holy object, is it fitting that it is today a sad and neglected garden ornament?[16]

[1] Li Weiwen, in correspondence with the photohistorian Terry Bennett, had noted that the bronze statue of the Buddha with its Tibetan style coronet, was on a wooden pedestal (see the carpentry joins at the corners), i.e., not made of either stone or bronze. This suggested that the Buddha was outdoors temporarily. The building behind it was not a temple/monastery, nor an ordinary house, rather it was built in a high-status style. Li Weiwen further observed variations in the brickwork, indicating new construction added to old. As the British Legation in Beijing was previously a prince’s palace and was much augmented by the British, Li proposed that the Legation could well be the exact location. Many thanks to Terry Bennett for sharing images from his collection with me.

[2] As well as the print in Moore’s album at the Irish Jesuit Archive (fig. 2), there’s another one in ‘Bibianne’s album’ (the album Moore’s wife, Bibianne Yii Moore, gave to Hester Hart) and also, in addition to the hand-coloured print (fig.1), there’s an uncoloured print in Terry Bennet’s Collection in amongst a set of known Moore photographs.

[3] Admiral Sir Henry Keppel, A Sailor’s Life Under Four Sovereigns (London: Macmillan, 1899), vol. III, p. 261.

[4] Keppel, A Sailor’s Life, vol. III, p. 260.

[5] The Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan & The Philippines, for the Year 1869 (Hong Kong: Daily Press, 1869).

[6] Keppel, A Sailor’s Life, vol. III, p. 261. Perhaps sensitivities about the looting of 1860 remained acute.

[7] Keppel, A Sailor’s Life, vol. III, p. 259.

[8] Keppel, A Sailor’s Life, vol. III, p. 260.

[9] Kenneth K.S. Ch’en, Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964), pp. 405-408. Many thanks to Professor Rupert Gethin for this reference.

[10] Mentioned in William Shawcross, Counting One’s Blessings: Duchess of York: The Selected Letters of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother (London: Macmillan, 2013).

[11] James Pope-Hennessy (ed. Hugo Vickers), The Quest for Queen Mary (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2018), p. 89.

[12] Letter from Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother to George V, 14 January 1924, quoted in William Shawcross, Counting One’s Blessings: Duchess of York: The Selected Letters of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother.

[13] Helen Cathcart, Sandringham: The Story of a Royal Home (London: W.H. Allen, 1964), p. 95; James Pope-Hennessy (ed. Hugo Vickers), The Quest for Queen Mary, p. 89; Mike Biles, ‘A Bit about Britain’; Elle Seymour, The Royal’s Smuggled House Warming Gift at Sandringham (2022).

[14] The Chinese Joss (‘John Chinaman’). Recording Archive for Public Sculpture in Norfolk and Suffolk (RACNS).

[15] Helen Cathcart, Sandringham, p. 96.

[16] The Chinese Joss (‘John Chinaman’). Recording Archive for Public Sculpture in Norfolk and Suffolk (RACNS).