Having just completed his PhD at Bristol, ‘Three Brothers in China: A Study of Family in Empire’, Andrew Hillier is now working on developing it into a book.

On 12 May 1846, Eliza Medhurst set off by boat from her family home in Shanghai. The daughter of missionaries, Walter and Betty Medhurst, she was on her way to Hong Kong to meet her fiancé, Charles Batten Hillier, the fledgling colony’s Assistant Chief Magistrate. They were married two weeks later. Over the next nine years, she gave birth to four surviving children. When Charles was appointed as Britain’s first Consul to Siam in 1856, he and Eliza moved to Bangkok. Within four months of their arrival, he had succumbed to fever and died. Eliza, pregnant once again, made her way back to England where she gave birth to Guy. Educated in England, three of the Hillier boys – Walter, Harry and Guy – returned to China in their early twenties, pursuing careers in three key institutions of Britain’s informal empire: the Consular Service, the Chinese Maritime Customs (CMC) and the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, as it was then called.

Their lives, and those of their forbears are recorded, in a collection of photographs, which will soon be accessible on the Visualising China web-site. A rich mixture of official pictures, studio portraits and informal snaps of family, friends and local scenery, they tell us much about the lives of Britons in China during the treaty port period, the importance of family as part of that presence and the connections it forged and cemented both with those in England and further afield. In the following selection, we can see how they illustrate the relationships between British and Chinese officials, formal and informal, the character of young men careering in China, the intimacy of their family life and, finally, their memorialisation.

1. ‘Student Interpreters, Peking, 1869’. Walter, aged 18, is at the front on the LHS, beardless.

Walter Hillier arrived in Peking as a student interpreter in 1868 and quickly proved himself a competent linguist on the Legation staff. In Plate 1, we see him with his colleagues shortly after his arrival. The photograph conveys a relaxed mood; it could have been taken in an English garden, with languid poses and dogs nestling on the rugs.

The next brother to arrive was Harry Hillier. Having passed the exams for the Customs Service, he arrived in China in 1871, aged 20. He spent the next forty years there, rising to the post of Commissioner, which he held in a range of treaty ports. Also fluent in Chinese, he established good relations with his Chinese counterparts on both a formal and informal level. The photograph at plate 2, taken when he was Commissioner in Nanking, shows a formal lunch-party held to celebrate the Emperor’s birthday in 1903. Harry is eighth from the right, with wing collar and beard, and is flanked by three Chinese officials on his right – the Superintendent of Customs, the Provincial Treasurer and the Viceroy. Unlike them, the Japanese officials to his left are in Western suits.

2. Lunch-party given by the Viceroy of the Two Kiangs, Wei Guangdao, on the birthday of the Emperor of China, 18 August 1903.

The picture was widely circulated (one copy is in the Sir Robert Hart Collection at Queen’s University, Belfast). With the Chinese officials in the foreground, the image is one of comity and there is no sense of subservience or condescension. A more informal photograph (Plate 3), taken when Harry was Commissioner in Kiukiang (Jiujiang) in 1904, shows him with three Chinese officials sitting outside in their winter coats; the mood seems relaxed, as if they were in casual conversation.

3. Harry with Chinese officials: the Daotai, Yung Ling on his left, the Magistrate, Tsung, on his far left and the Foreign Affairs Deputy, Li on Harry’s right. Kiukiang, 18 December 1904.

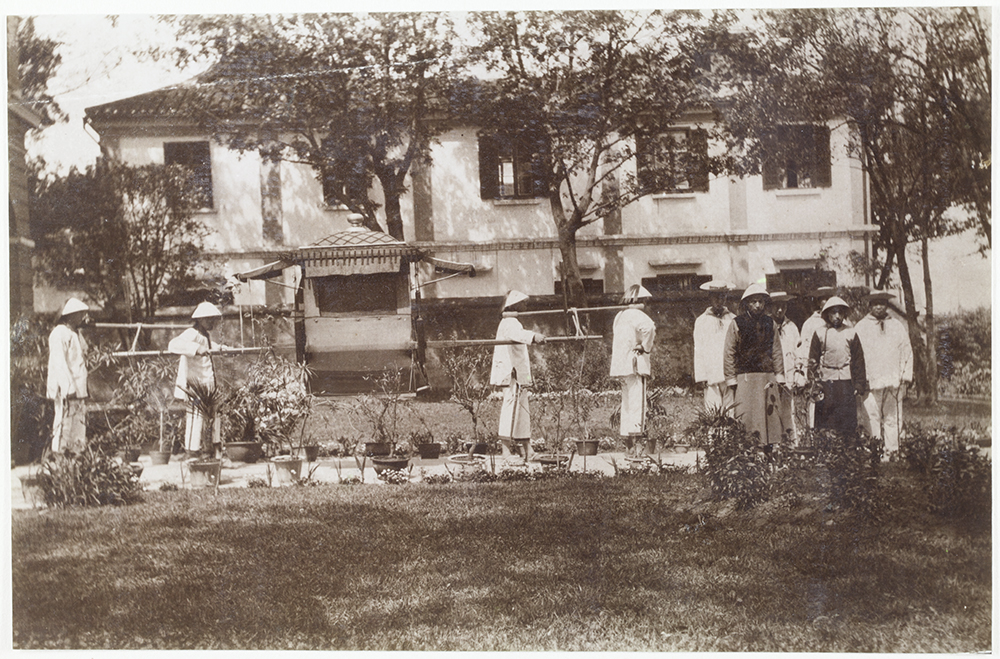

Ceremony, however, was an important element of official life and Harry would send home to the family in England photographs with captions describing the elaborate rituals, as we see in Plate 4.

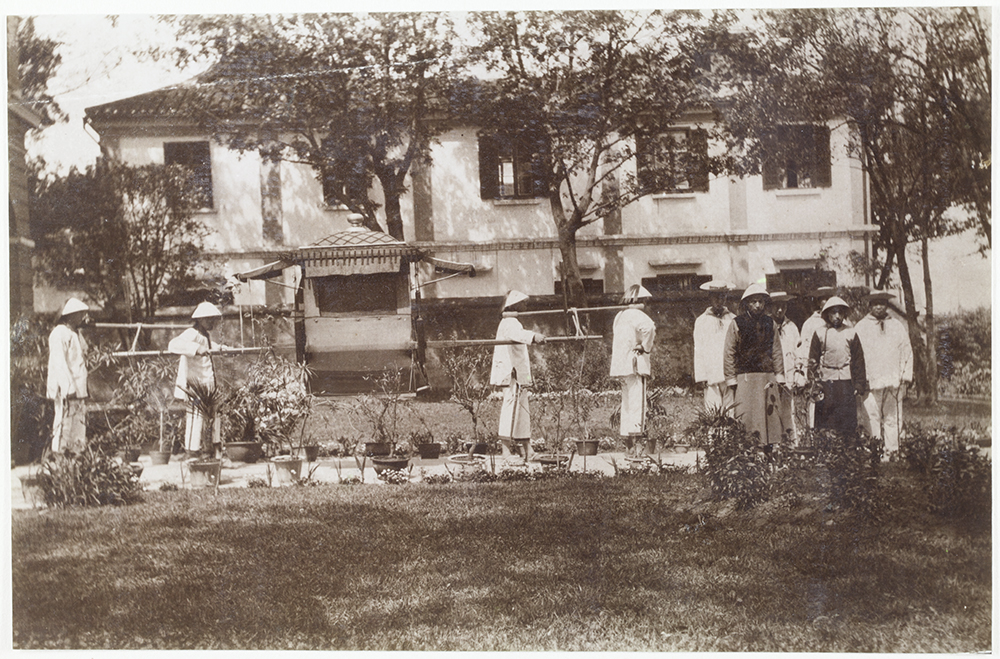

4. Kiukiang, 1904. ‘My official chair and bearers with official servants waiting in the garden for me to go on a round of official calls. The building at the back is the Chinese Post Office of which I am Postmaster’.

A keen photographer, Harry may well have taken this picture himself and, if so, his ‘official servants’ will have been asked to pose for the Commissioner.

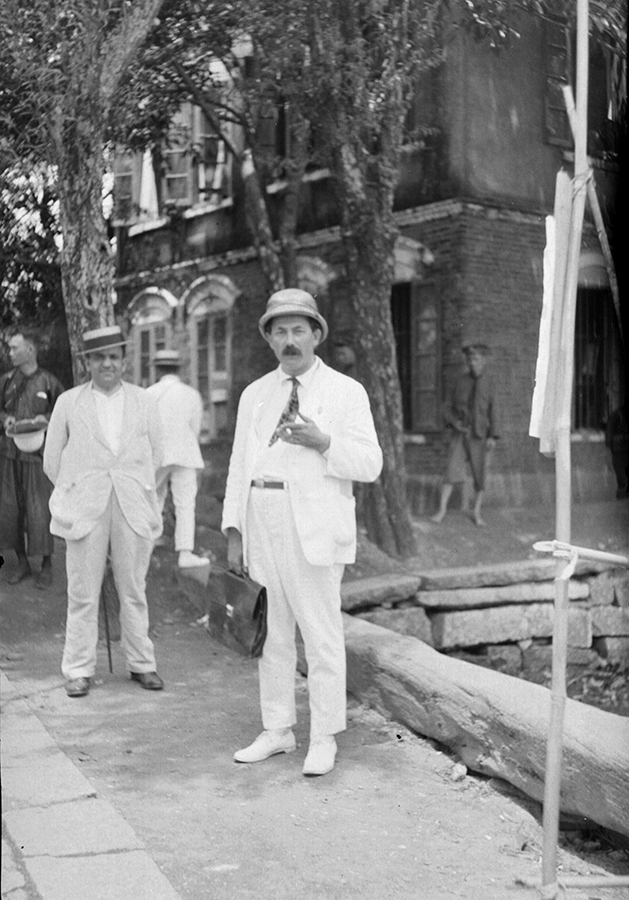

Guy Hillier followed his two brothers to China and, after various false starts, was taken on by the Hongkong Bank in 1883, largely because of his ability to speak Chinese. Eight years later, he was appointed the Bank’s first Agent of its Peking branch. The picture at plate 5 must have been taken at this time. With his floppy cap, one hand holding a cigarette and the other in his pocket, he exudes a certain nonchalance tinged with an impatience to get going.

5. Guy Hillier with Bank staff, c. 1891.

A few years later (Plate 6), with the success of the Peking agency, the setting is more formal.

6. Guy Hillier, centre, with Bank staff, c. 1896.

The three Hillier brothers were extremely close but only once worked in the same city when all three were in Peking in 1908, when Walter was a Political Adviser to China (plate 7).

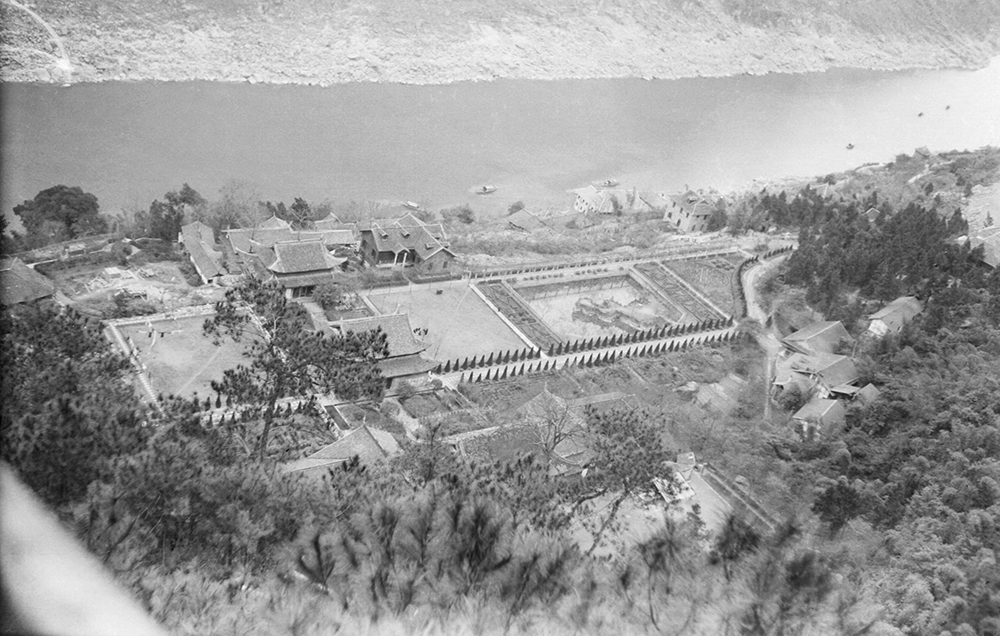

7. Pali-chuang Temple, c. 1908, where Guy had his own ‘suite’ of rooms provided by the Buddhist monks for his week-end retreat. From left, Harry, Guy, Walter.

The three brothers experienced very different marriages. Having lost his first wife, Lydie, Walter re-married. In Plate 8, we see his second wife, Clare, and Harry’s first wife, Annie. The picture was taken in England when Harry was assigned to the London office and Walter was on long leave. In due course, Hart would take a shine to Clare, and, as his diary shows, enjoy a modestly flirtatious relationship with her. Her marriage to Walter ended in divorce and Harry’s wife died from typhoid, her health badly affected following the birth of their only child, Eddie.

9. Walter and Clare, Harry and Annie, c. September 1882, London.

Harry’s second wife, Maggie, was the daughter of the well-known Shanghai barrister, William Venn Drummond. As we see in Plate 10, the family was presided over by his wife, Christian Forbes Drummond (née Macpherson). Guy also features in the picture as he was often a guest, both at this time, 1890, and later, when Drummond built one of Shanghai’s most sumptuous mansions, Dennartt (Plate 11). Drummond’s practice was based on a substantial Chinese clientele, official and mercantile, many of whom he entertained in his home. Shorn of its sumptuous grounds, it can still be found down an alley-way leading off the Huashuan Road (formerly the Siccawei Road). Since it is now a government building, I had to evade the vigilant security guards to take the photograph at plate 12.

10. Drummond Family Portrait, 1 January 1890.

11. Tea on the Lawn, Dennartt, Shanghai, c.1906.

12. Dennartt, 2014. Author’s photograph.

Guy Hillier married Ada Everett in 1894 but, shortly after the birth of their fourth child, Tristram, in 1905, she and the children returned to England and seldom saw Guy again, a typical example of a distant empire marriage. Only one faded photograph remains of Guy and Ada together (Plate 13).

13. Guy and Ada Hillier, c. 1894.

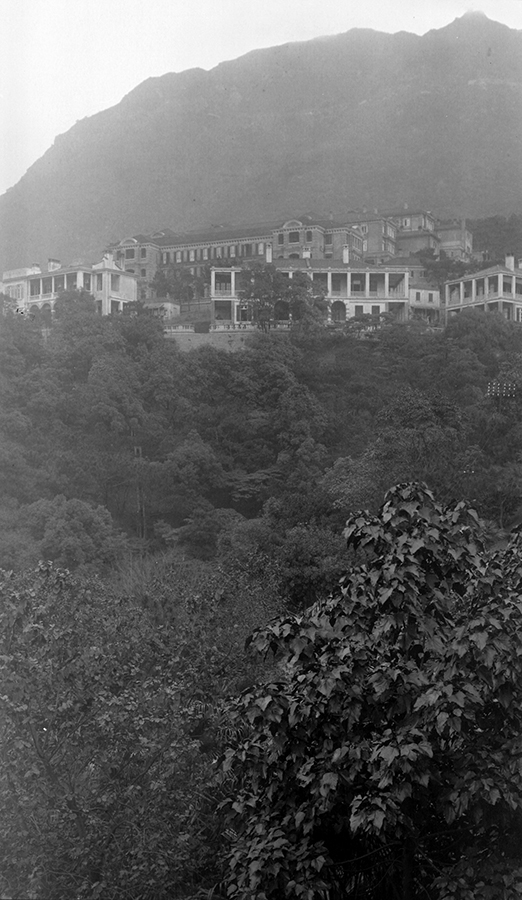

By contrast, Harry’s family always remained closely-knit, despite lengthy painful separations. During his appointment as Commissioner of Kowloon (1895-1899), they lived on the Peak in Hong Kong. The studio portrait, taken shortly before their departure, conveys a sense of family unity and an intimacy which they knew was soon to end (plate 14).

14. Harry and family: children from left: Geoff, Eddie, Harry and Dorothy.

Hong Kong, c. 1898.

After Harry’s retirement in 1910, the children would visit their home in the Sussex countryside. The picture at plate 15 was taken shortly before the outbreak of the First World War in which both Harold and Geoff fought.

15. Burnt Oak, Waldron, Sussex, c. 1913. Harold, Geoff, Dorothy, Maggie, Harry and Bertie, Dorothy’s son, in pram.

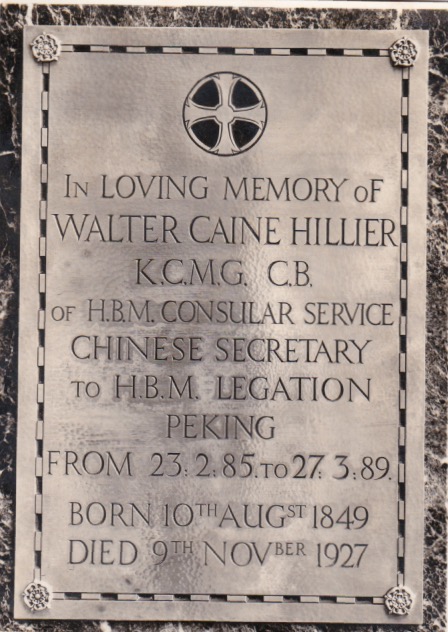

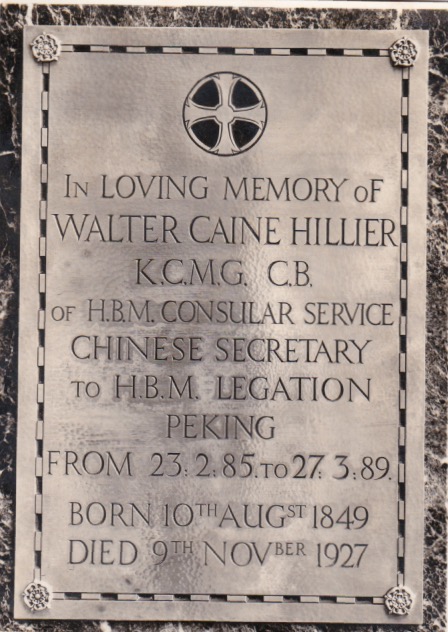

On 30 March 1918, Geoff was posted as missing in action. Harry died six years later and the simple gravestone in the churchyard of St Mary’s, Wimbledon, bears both his name and that of Geoff, but there is no reference to his service in the CMC. By contrast, two memorial plaques, one in Holy Trinity, Bracknell and one in the grounds of the Peking Legation, record Walter’s service in China (plate 16).

16. Walter Hillier, memorial plaque, British Legation, Peking.

Unlike Walter and Harry, Guy continued working until his death in 1924. And, unlike them, his funeral was a lavish affair attended by the entire officialdom of Peking, Chinese and European, along with his many friends. Initially buried in the French Jesuit cemetery at Peitang, his and all the other graves were later exhumed and the remains reinterred in Waiquiao Cemetery on the outskirts of Beijing. Whilst almost all the gravestones were then destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, including the cross surmounting Guy’s grave, the substantial granite slab survived, together with its inscription, Sans Peur et Sans Reproche (plate 17). Subject to permission, it can still be visited, surrounded by rows of uniform Chinese tombstones. His is one of a number of family graves, in both China and England, whose inscriptions memorialised and consolidated the British presence in China.

17. Gravestone of Guy Hillier, Waiqiao Cemetery, Beijing, 2014. Author’s photograph.

This collection shows how family formed an important mechanism for forging and consolidating the links that helped bind together the British world in east and south-east Asia across four generations, from the time of Walter and Betty Medhurst’s arrival in Malacca in 1817 to the departure of the last members of the family in the 1930s.

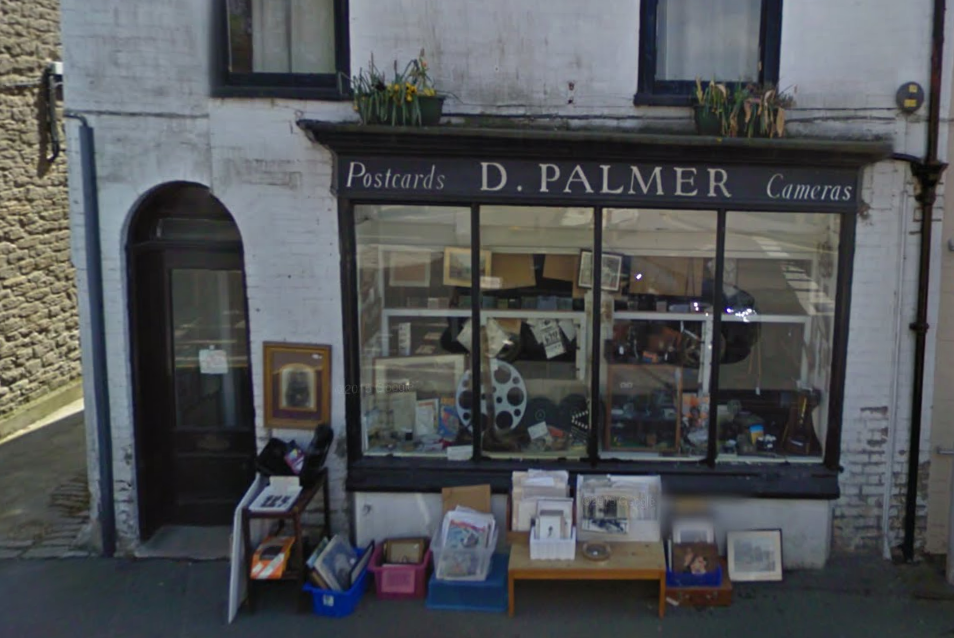

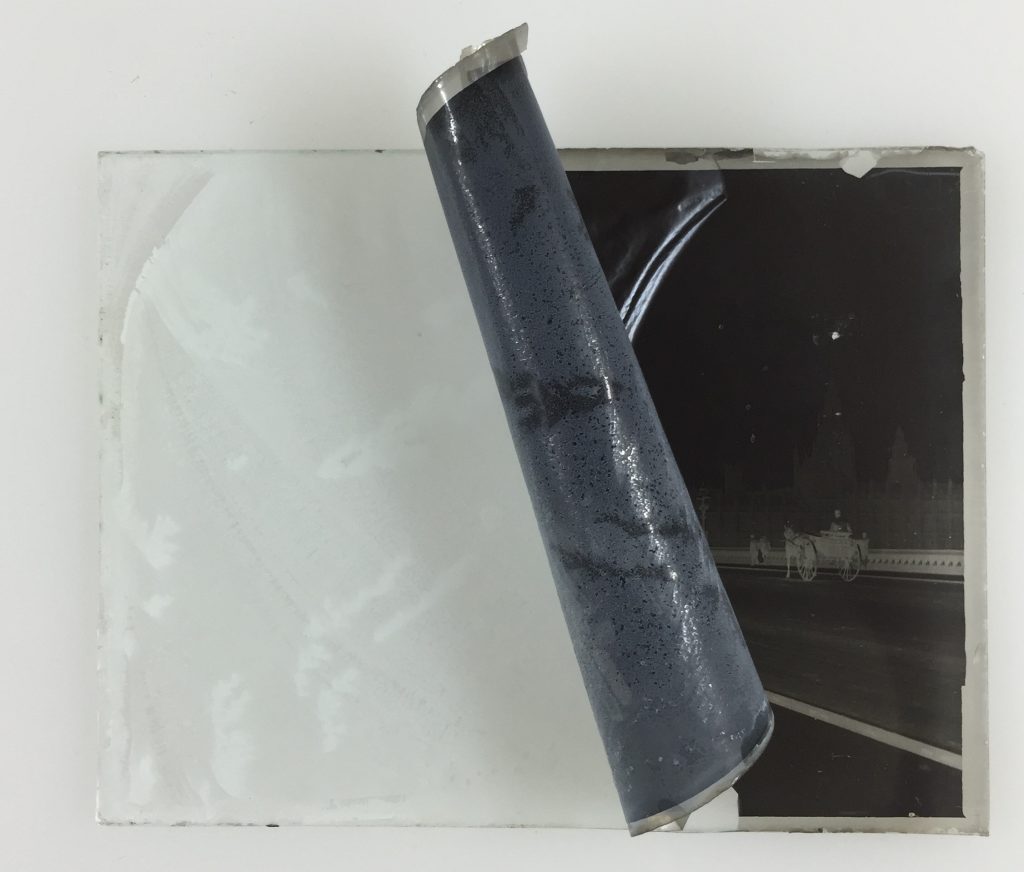

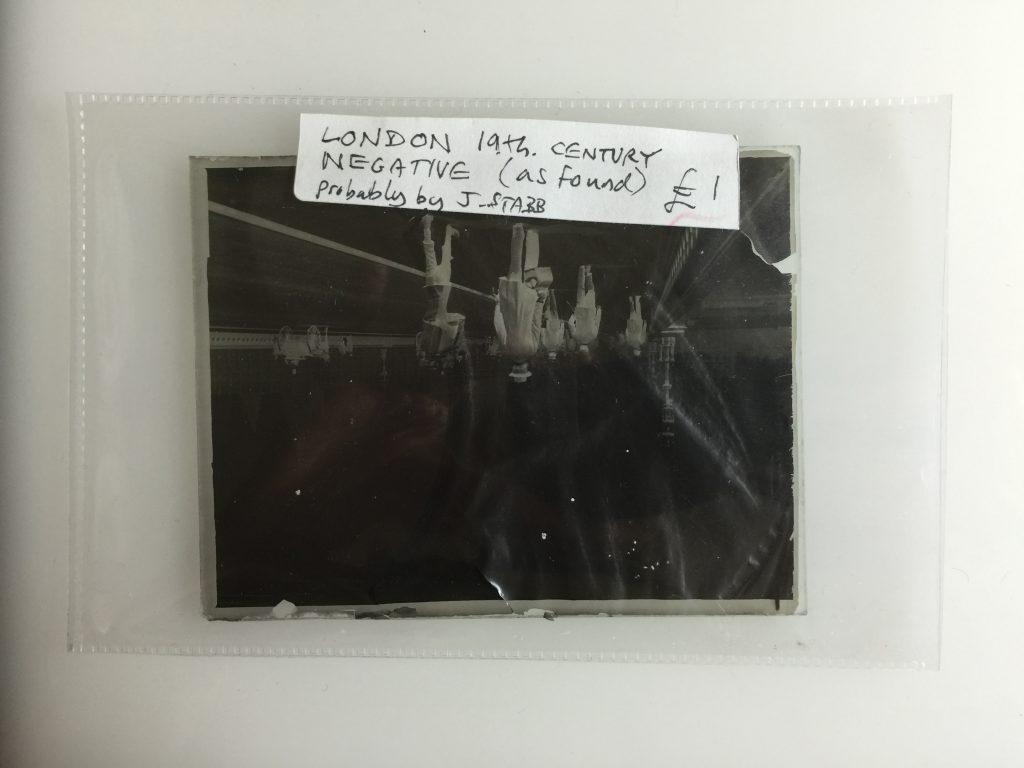

Some of the photographs and negatives we are presented with are beyond salvage, but it can be worth persevering. The following episode has no China connection, but perhaps indicates what might be done with any seemingly hopeless case. It is also an example of what might be done with a found object. A favourite shop of mine sits on West Allington on the western edge of Bridport town centre in Dorset. D. Palmer, trading online as ‘Film Is Fine’, is stuffed with old film and photographs, cameras and projectors, postcards and associated ephemera. It’s a wonderful shop.

Some of the photographs and negatives we are presented with are beyond salvage, but it can be worth persevering. The following episode has no China connection, but perhaps indicates what might be done with any seemingly hopeless case. It is also an example of what might be done with a found object. A favourite shop of mine sits on West Allington on the western edge of Bridport town centre in Dorset. D. Palmer, trading online as ‘Film Is Fine’, is stuffed with old film and photographs, cameras and projectors, postcards and associated ephemera. It’s a wonderful shop.

![Fig. 2 View of Northern Hot Springs Park from Jialing River. Source: Lang Jingshan.,Chuan zhongming sheng xuanji: Beiwenquan [Selections of Scenic spots in the middle of Sichuan Province]. Xingguang (Singapore), no.1 (1939): 36](https://hpchina.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2016/08/Fir-2.png)