Josepha Richard is a PhD candidate at the University of Sheffield, specialised in Modern China and the gardens of 19th century Guangzhou. She holds an MA in Chinese studies (Leeds University) and Art History (Sorbonne Paris IV) and was recently a Summer fellow at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C.. She regularly tweets about historical pictorial sources of China at @GardensOfChina.

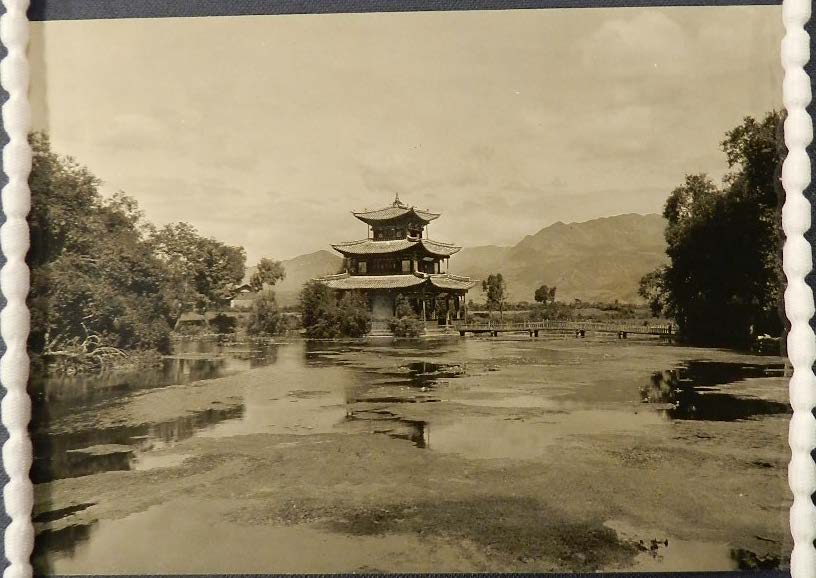

Photograph 1: Photograph 486, Joseph Rock Collection, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Photo: J. Richard

As any person who ever had a garden knows, it takes constant care and careful know-how to prevent greenery from returning to a state best described as ‘Sleeping Beauty’s castle thorns’. By essence, gardens are ephemeral, thus difficult to document consistently and systematically. The gardens of China are no exception to this rule: as a result, it can be difficult to study any specimen built earlier than the late Qing dynasty. To research the gardens of China, the specialist needs to collect a combination of sources such as written descriptions, paintings and photographs.

One of the most revealing types of primary sources is that of early photographs of China. These are typically scattered across a number of private and public collections, as well as auction houses: obtaining good quality items with reliable captions, attributions and dates is an arduous task. One example I have come across during my research is that of Austrian-American explorer Joseph Rock, who travelled to the Black Dragon Pool in Lijiang, Yunnan, and took at least two photographs of the garden there. Those two shots are kept in two different institutions across the globe: the Arnold Arboretum image provides us with the date of 1922, while the photograph kept in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh in Edinburgh (Photograph 1) is accompanied by matching diaries written by Rock during that year and kept in the same archive.

This ideal case of matching collections is rare, and individual, incompletely documented photographs are much more common. Indeed, the number of 19th century Chinese gardens ever visited by a photographer represent a small minority, and therefore, it is crucial that museums, archives and private collectors continue to make their collections available online. Furthermore, initiatives such as the ‘Historical Photographs of China’ project are much needed to uncover precious private collections that are the hardest for researchers, collectors and amateurs to reach.

To further complicate matters, coincidence played a primary role in the making of early photographs of gardens in China. The first cameras were taken to China at the end of the First Opium War (1838-42) at a time when Guangzhou was still the primary harbour for Western visitors, and therefore, many photographs of Cantonese gardens have survived while the original gardens have not. This precious evidence would not have existed if the camera had been invented a few decades later, when the consequences of the Second Opium War meant that Westerners progressively lost interest in Guangzhou (Canton) in favour of other Treaty Ports that had opened across the country.

Photograph 2: Howqua’s gardens, Canton. Albumen print, 1860, by Felice Beato (1832-1909). Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

During the Canton Trade or System period (1757-1842), in which all trade was confined to Guangzhou, construction of gardens around the city intensified due to the flow of wealth originating from the China Trade. Throughout the Canton Trade period, merchants wanting to do business with China were obliged to use specific intermediaries during their transactions: the Co-Hong or Hong, who profited immensely as a result (although many eventually became bankrupt). Until the 1st Opium War, Hong residences were among the only locations that Western visitors could visit in China, and apparently remained attractive for sightseeing well after the end of the Canton System. The most notable examples are residences with gardens built by Pan 潘 and Wu 伍 families, both linked with Hong merchants.

As a consequence of the Western presence in Guangzhou during the Canton System period and beyond, sources documenting Hong gardens are exceptionally abundant, especially when it comes to the amount of pictorial evidence available. The comparison of traditional and export Chinese paintings as well as photographs allows for deeper analysis of those gardens than is usually possible for such an ephemeral subject. It is, for example, very fortunate that the Frenchman Jules Itier took the earliest extant photographs in China in 1844 while visiting Macau and Guangzhou. Three of his daguerreotypes depict a garden of the Pan family, the Haishan xianguan 海山仙官. In my doctoral thesis, I compare these images with other sources – for example, the Caleb Cushing papers kept in the Library of Congress.

Photograph 3: Canton, Part of Chinese garden. Postcard produced by M.Sternberg & Co. in Hong Kong, around 1909, from earlier photograph of unknown date. Scan: J. Richard.

The gardens of Howqua – of the Wu family – are similarly documented : different views are available in several formats, for example the stereoscopic card taken by the Swiss Pierre Joseph Rossier in 1855-62 and held at the Rijksmuseum. This view, focused on one feature of the garden – a water-based kiosk – can be contrasted with a 1870s albumen of the same pond available on the Bonhams website from past sale lot 173. Interestingly, the same kiosk is found on the painted background of a series of portraits such as the “Actors in Canton” shot taken by C. R. Hager around 1896-1905 and found on the Basel Mission website. Felice Beato took a wider view of Howqua’s garden in 1860, just before the photographer accompanied Franco-British troops to Beijing (Photograph 2). An undated postcard bought online represents the garden from yet another viewpoint and gives a better insight into the layout (Photograph 3).

By cumulating these different photographs, a vivid representation of the Hong gardens can be obtained, allowing us to catch a glimpse of the colourful background of some 19th century East-West encounters.

PS: I welcome any suggestions or tips about photographs of gardens that could have been taken in 19th and early 20th century Guangzhou and the surrounding areas.