Dr Helena F. S. Lopes is currently a Senior Research Associate in the History of Hong Kong and a Lecturer in Modern Chinese History at the University of Bristol. She holds a DPhil in History from the University of Oxford. Her research interests include transnational encounters in South China during the Second World War.

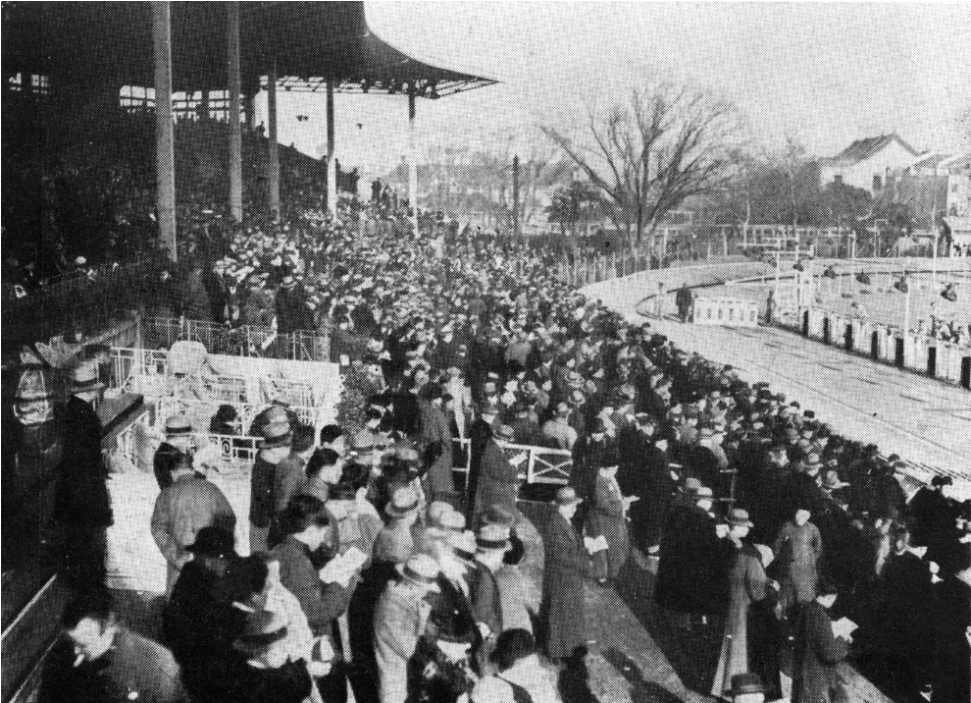

Found between images of refugees and nurses, the photographs of women sewing clothes in 1937 Shanghai (here and here) are hardly the most obvious when discussing a global war. This seemingly banal activity is one that goes on in peacetime as well during conflicts. Yet, times of crisis make clear how much of an essential service this is, everywhere in the world. The current COVID-19 crisis is of course no exception. In accounts of the Second World War in China, making clothes is sometimes mentioned as one of the key activities through which women – this was an activity made mostly by women – supported the war effort. Sewing by hand or with the help of machines, women made uniforms for those serving in the frontline (including, of course, health workers as well as soldiers) and clothes for the destitute, and continued to make garments for everyday use. These images of resilience have obvious transnational parallels and perhaps it was a sense of familiarity that drew the attention of the American photographer Malcolm Rosholt who took those photographs. War is often dominated by dramatic shots of military operations or their devastating effects in humans and the environment but these photographs suggest something of the constructive activities done by those left in the shadows, often lacking recognition for their wartime contribution.

If histories of the Second World War were until fairly recently (and one could argue, still are to a large extent) marked by male-centred narratives, they were also dominated by Eurocentric and American-centric perspectives. However, in recent years, new studies challenging some of the ways in which the conflict had previously been presented in English have begun to enter mainstream discussion. For example, the three volumes of the Cambridge History of the Second World War, published in 2015, have several chapters covering East Asia.

The conflict in China is still more commonly known as the Second Sino-Japanese War, or, in China itself, as the War of Resistance Against Japan (抗日戰爭 KangRi zhanzheng), but many studies of the social, military, political, and diplomatic dimensions of the war in China published in the last few decades engage directly with that conflict’s place in a global Second World War. For a representative list of these studies, see the bibliography below.

The start of a global World War Two continues, to a considerable extent, to be placed in Europe in September 1939, but when looking beyond the standard starting point in central Europe – for example, to China, Ethiopia or Spain – other possibilities make sense as well.[1] One of them is 1937, when an all-out war began between China and Japan. Others may argue that was a mere regional conflict which did not lead to the start of a conflict engulfing the whole world. But neither did that happen with the war in Europe in 1939 – only in 1941.

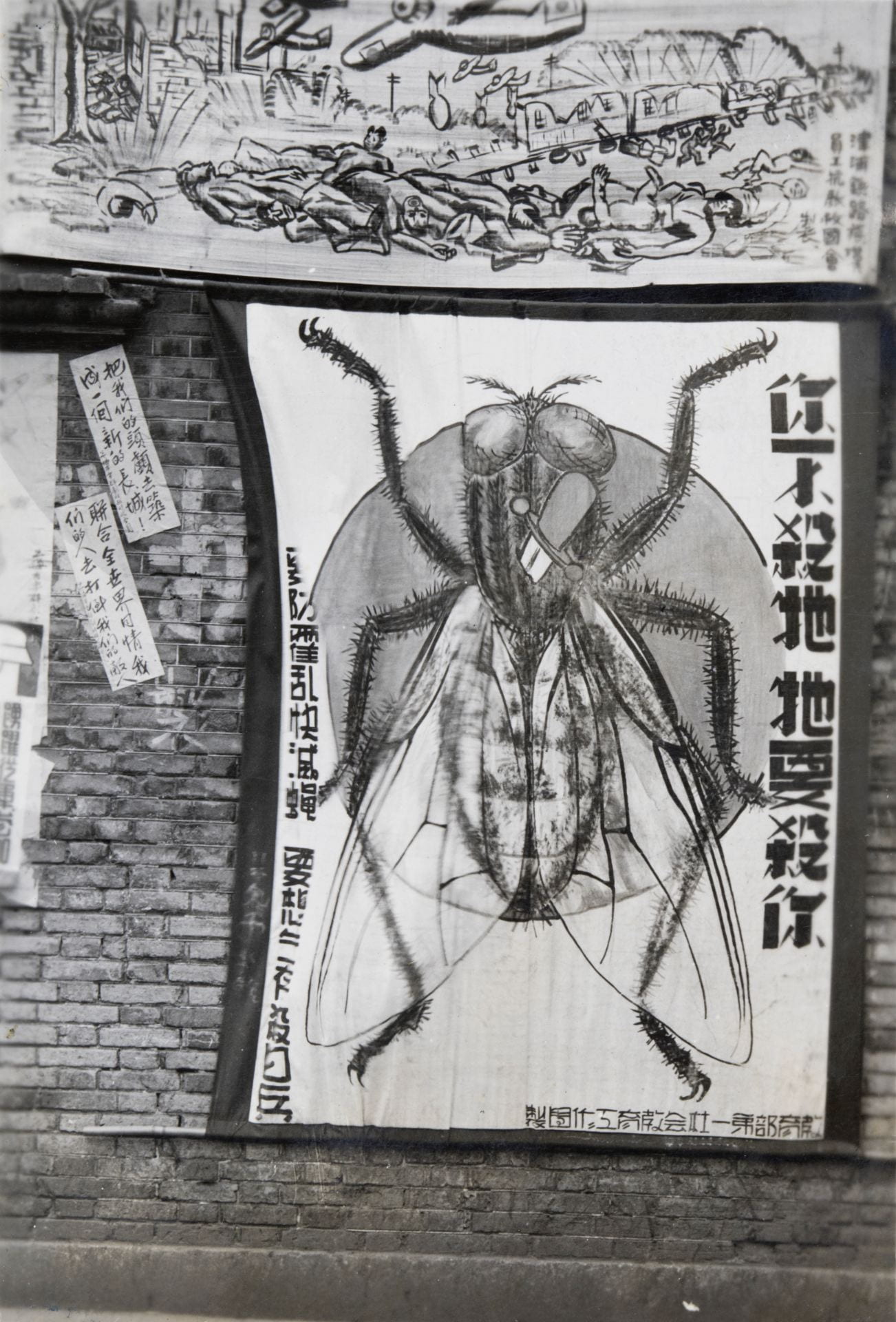

The conflict in China was extensively covered by the overseas press at the time, including by photographers and documentary film makers, but would come to be overshadowed by the onset of the conflict in Europe. The official start of war in China is now 1931, not 1937, the opening salvo of the Sino-Japanese conflict being placed in the Manchuria Crisis, which started with the Japanese military invasion of the Chinese Northeastern provinces and led to the gradual occupation of parts of North China. The start of a continuous state of warfare in July 1937 surely marked a crucial turning point, though it is important to note that a culture of resistance, with a dimension of transnational mobilisation, existed long before.

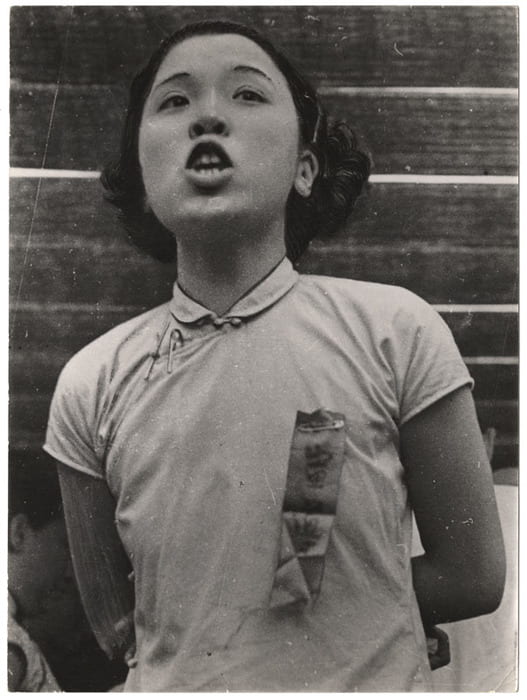

A woman speaking at a parade commemorating the thirteenth anniversary of Sun Yat-sen’s death and the first anniversary of the Sino-Japanese War, Hankou, China. Photograph by Robert Capa. © Cornell Capa.

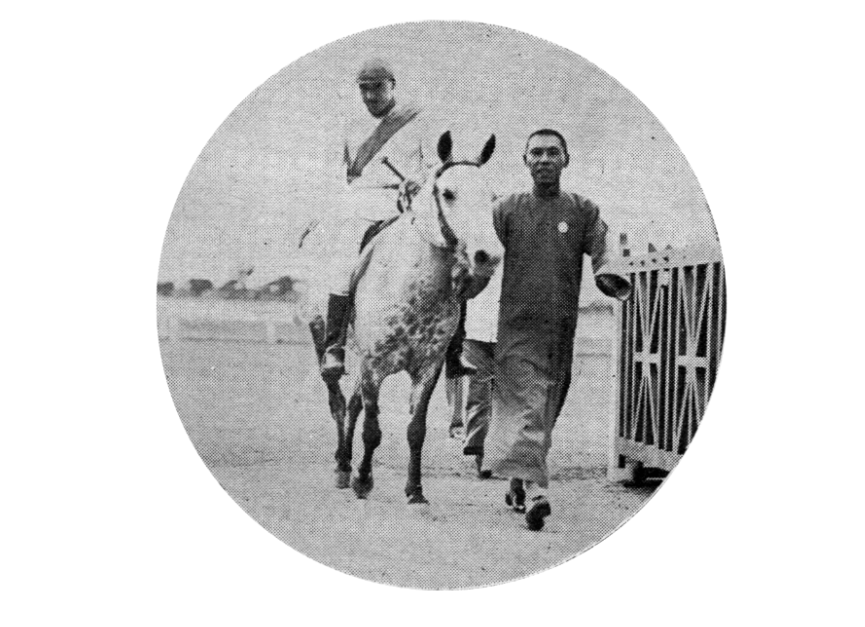

For many in the 1930s, the war being fought in China had clear connections to those being fought in Spain or in Ethiopia. In other words, at least for some people, this was understood as a transnational conflict from early on. And whilst there were patches of nominal neutrality in the early phases of the Sino-Japanese War, notably concessions and colonies under foreign rule, even these were marked by global interactions connected to different dimensions of the conflict, including legal and illegal commercial activities.

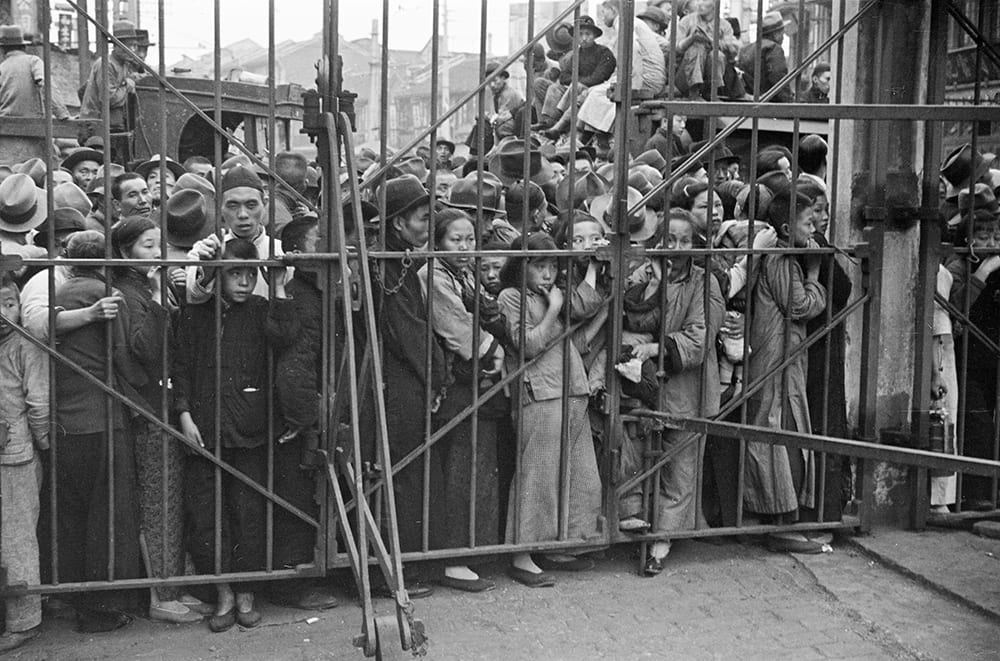

The Historical Photographs of China Project (HPC) holds numerous images where we can find concrete visual traces of a global Second World War in China. The collection of Malcolm Rosholt photographs shows Shanghai in the early stages of the war in the summer of 1937. We see the physical markers of a divided metropolis, between Chinese Municipality grappling with a Japanese invasion and the supposedly neutral International Settlement and French Concession. But his photographs also show how the momentous impact of the conflict transcended those divisions in different ways and forged new connections, even if unintendedly. Rosholt’s photographs chronicle old and new faces of a global city at war. We find, amongst others, Chinese and Japanese soldiers, Sikh policemen, the French Jesuit missionary Robert Jacquinot de Besange who headed the Shanghai Safety Zone, and refugees fleeing the violence of the war and seeking shelter across the borders that had been drawn around zones of foreign residence and power, and sanctuary, in the city.

Some images provide subtle reminders of the many global connections coming together in wartime China. See for example, the photographs of Chinese Boy Scouts standing in front of a banner for a ‘Red Cross Society of the Republic of China’ hospital. These are two different symbols of an internationalised Nationalist China that gained new life during the conflict.

Boy scouts outside Shanghai Stock Brokerage Corporation office (serving as a Red Cross hospital), Shanghai. Photograph by Malcolm Rosholt. HPC ref: Ro-n0156.

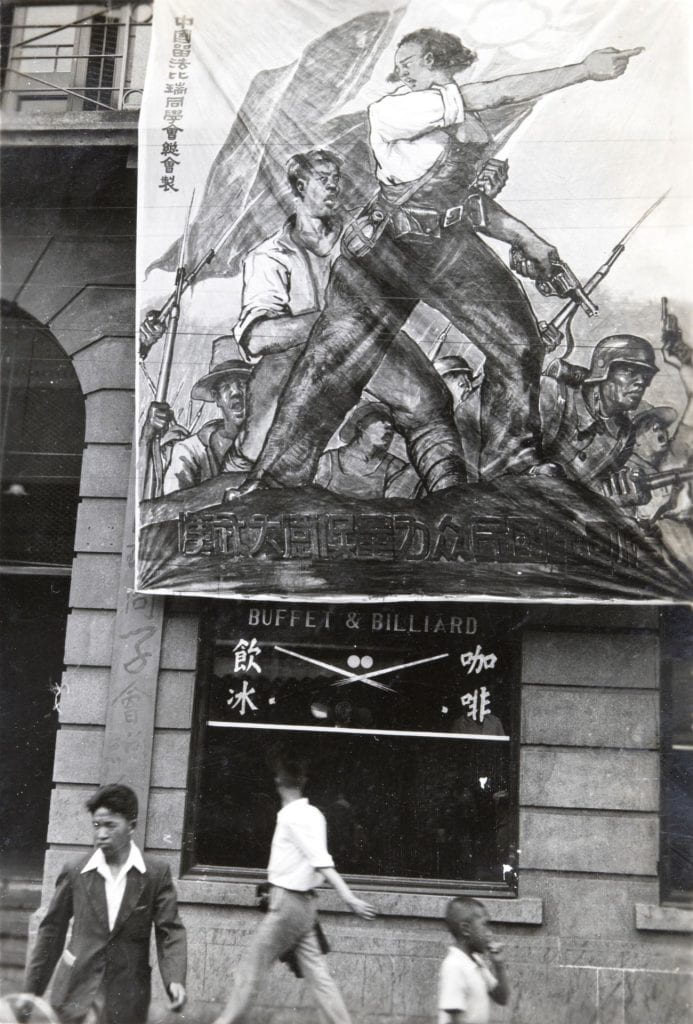

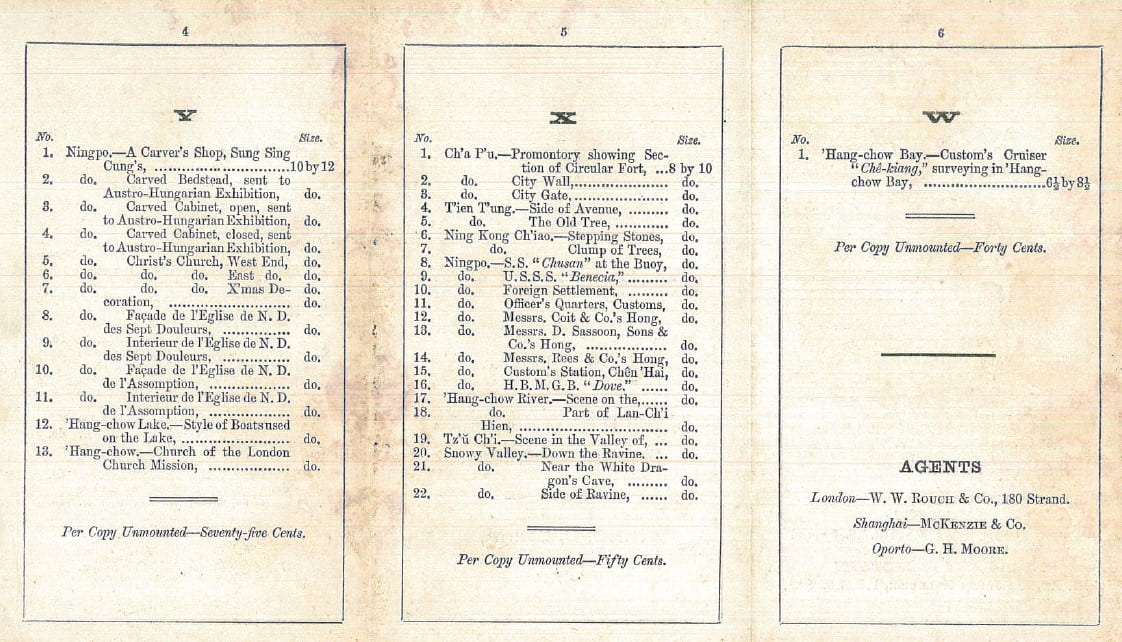

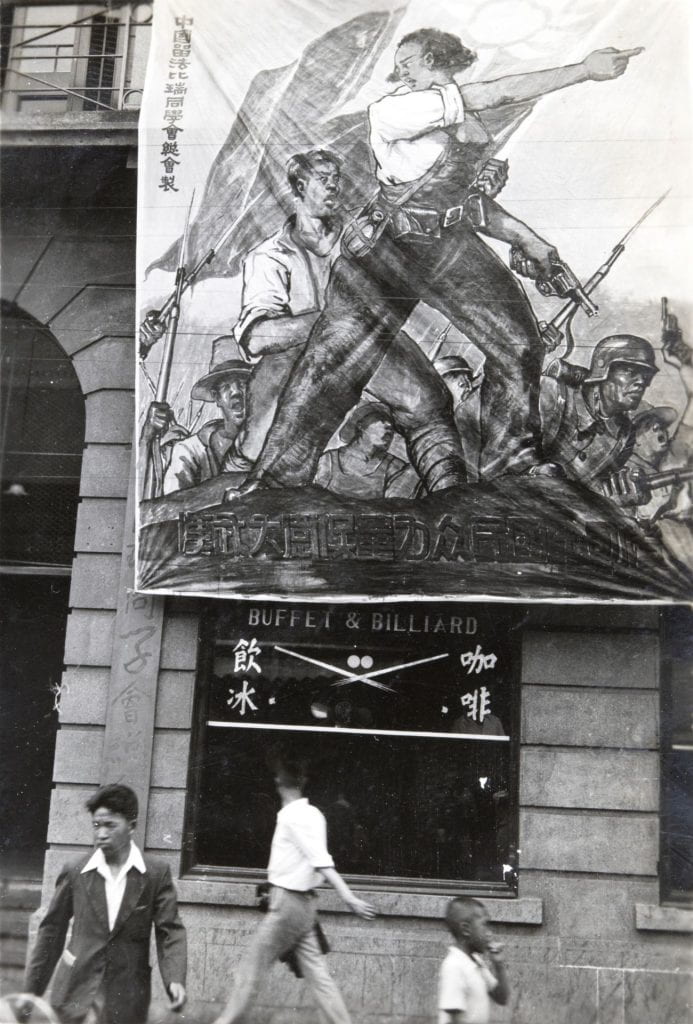

Other traces of China’s position in a global World War Two can be found in some of the Wuhan photographs among the HPC holdings, which have merited other posts in this blog. It is the case of this pro-resistance banner outside the headquarters of the France, Belgium and Switzerland Returned Students Association (L’Association des Etudiants Chinois de Retour de FBS) – the location from where Robert Capa took one of his iconic photographs of wartime China. Capa was one of many – including the Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens with whom he had come to the country – to draw parallels between the Spanish Civil War and the Sino-Japanese conflict. The role of Chinese communities overseas, including, but definitely not limited to, students is an important dimension when studying transnational connections in China during the war.

Banner outside the headquarters of “L’Association des Etudiants Chinois de Retour de FBS”, Wuhan. HPC ref: Bi-s162.

The visual record of China’s global war is made of many anonymous faces, but it also includes prominent individuals, both men and women. One of them, which had featured prominently in Iven’s 1938 documentary The 400 Million – in whose production Capa had worked – was Soong Ching-ling [Song Qingling]. The widow of Sun Yat-set and the sister of Madame Chiang Kai-shek, Soong Ching-ling founded the China Defence League and was at the forefront of transnational networks of support for China’s resistance. Amongst others, she was photographed by Cecil Beaton, a British photographer who visited China as part of his wartime work for the Ministry of Information. Beaton also documented the conflict in other parts of the world. Many of his wartime photographs can be found at the Imperial War Museum, London.

Half length portrait of Madame Sun Yat-sen, in Chongqing. Photograph by Cecil Beaton. © IWM IB 3459C.

There were multiple forms of Sino-foreign cooperation in the war, both civilian and military. From formal alliances to shadow diplomacy, from transnational institutions to personal relations, these left traces in different types of sources and attest to the variety of ways in which China was connected to the world and how the war in East Asia was connected to other theatres of the Second World War. HPC includes images of some of these various encounters, including of Sino-British intelligence cooperation in the 1940s evident in the photographs of the Stanfield Family Collection.

This collection also includes several photographs of the official ceremony of Japanese surrender in Beijing. Such events, often understood from national frameworks, were actually quite global: they had international consequences and drew observers and participants from different nations, in this case including Hankou-born John E. Stanfield, who served in the Special Operations Executive Far East Force 136 and signed the surrender documents of the Japanese forces in North China on behalf of the British Army.

Important international connections framed experiences of resistance but these were also present around practices of collaboration. A window into this can be found in the images of foreign diplomats attached to the collaborationist Reorganised National Government which, amongst others, were recently made available by Stanford University in cooperation with the Cultures of Occupation in Twentieth Century Asia Project at Nottingham.

No reference to China’s role in a global World War Two would be complete without mentioning its main wartime capital, Chongqing, which became a major political, diplomatic and cultural centre during the war. The Fu Bingchang Collection holds a series of incredible images of life in the city. The image below, of a party accompanying Fu at the San Hua Ba airport in Chongqing as he left to take up the post of Ambassador to the Soviet Union is one of the many images in his collection that provide a visual record of the rich history of Republican China’s wartime diplomacy. Chongqing also features in other images. The Joseph Needham Collection offers photographic evidence of knowledge exchange taking place in the 1940s through the Sino-British Science Co-operation Office which Needham directed in the city.

Even though important new work has been appearing recently on China’s wartime experience, several of its global connections remain unexplored and should keep historians busy for many years to come. The HPC collections will no doubt provide useful material for those of us interested in the complex history of the conflict in China and its many transnational links.

[1] Even for Allied War Crimes teams investigating cases in China, the definition of the conflict was set by the German invasion of Poland: Robert Bickers, Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai (London: Allen Lane, 2003), pp. 326-27.

A few reading suggestions on China in a global war:

- Christian Henriot and Wen-hsin Yeh (eds), In the Shadow of the Rising Sun: Shanghai Under Japanese Occupation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004)

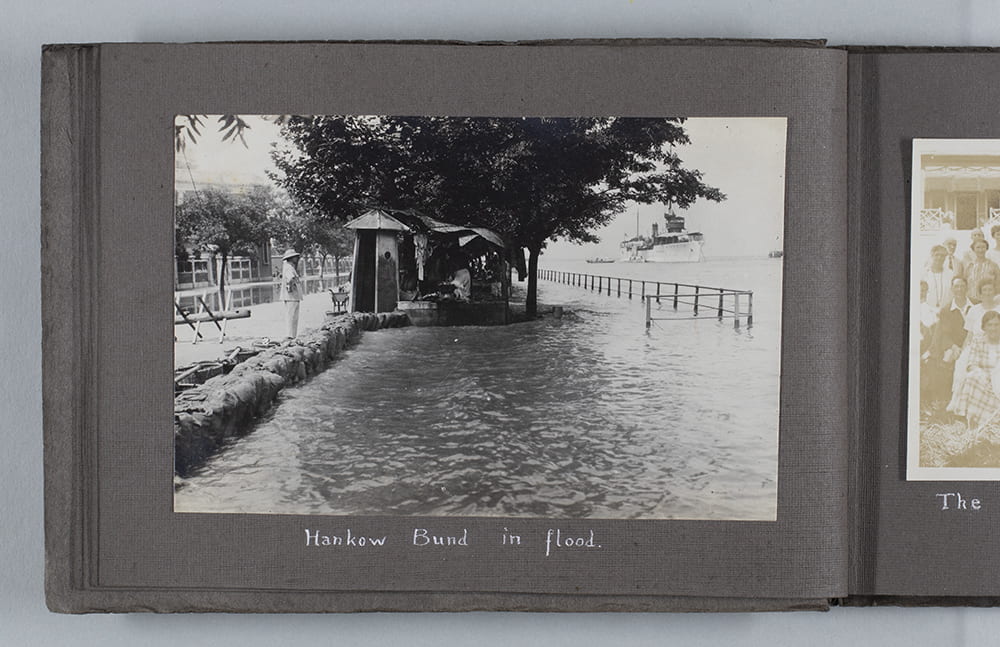

- Stephen R. MacKinnon, Wuhan 1938: War, Refugees, and the Making of Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

- Rana Mitter, China’s War with Japan 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival (London: Allen Lane, 2013)

- Aaron William Moore, Writing War: Soldiers Record the Japanese Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013)

- Marcia R. Ristaino, The Jacquinot Safety Zone: Wartime Refugees in Shanghai (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008)

- Hans van de Ven, China at War: Triumph and Tragedy in the Emergence of the New China 1937-1952 (London: Profile Books, 2017)

- Hans van de Ven, Diana Lary, and Stephen R. MacKinnon (eds), China’s Destiny in World War II (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014)

- Shuge Wei, News Under Fire: China’s Propaganda Against Japan in the English-Language Press, 1928-1941 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2017)

- Wen-hsin Yeh (ed), Wartime Shanghai (London: Routledge, 1998)

- Pingchao Zhu, Wartime Culture in Guilin, 1938-1944: A City at War (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015)

- Journal of Modern Chinese History, 13:1 (2019) – special issue ‘Wartime Everydayness in China during the Second World War’

- Modern Asian Studies, 45:2 (2011) – special issue ‘China in World War II, 1937-1945: Experience, Memory, and Legacy’

On photography:

- Shana J. Brown, ‘Sha Fei, the Jin-Cha Pictorial, and the Documentary Style of Chinese Wartime Photojournalism’, in Christian Henriot and Wen-hsin Yeh (eds.), History in Images: Pictures and Public Space in Modern China (Berkeley, 2012), pp. 55-80

- Christian Henriot, ‘Wartime Shanghai Refugees: Chaos, Exclusion, and Indignity. Do Images Make up for the Lack of Memory?’, in Henriot and Yeh (eds.), History in Images, pp. 12-54

- Jeremy Taylor, ‘The “Occupied Lens” in Wartime China: Portrait Photography in the Service of Chinese “Collaboration”, 1939-1945’, History of Photography (2019)