Our latest blog comes from Dr Yang Chan, Shanghai Jiaotong University. A graduate of Hunan University, Dr Yang was awarded her PhD at the University of Bristol in 2014, and then worked at Wuhan University, before moving in 2017 to Shanghai Jiaotong University where she is now Associate Professorship in the Department of History in 2017. A historian of wartime and post China, her first book, World War Two Legacies in East Asia, China Remembers the War, was published by Routledge in 2017.

The Yellow Crane Tower (Huanghelou 黄鹤楼) is probably the most famous landmark in Wuhan. Located at the confluence of Yangzi and Han rivers, it was built originally as a military watch tower during the Three Kingdoms period in 223 AD. In the course of history, it gradually became a well-known scenic spot. The Yellow Crane Tower has been destroyed many times and rebuilt, repeatedly, across the centuries. The present version is based on a Qing Dynasty reconstruction, which was destroyed by fire in 1884. The photograph below was taken by a studio owner in Wuhan, just before this 1884 disaster).

The Yellow Crane Tower (黄鹤楼), Wuchang (Wuhan). Photograph by Pow Kee, whose studio was to the right of the pagoda. A scan of a magic lantern slide © 2019 Royal Asiatic Society. Historical Photographs of China ref: RA-m122.

Numerous men of letters visited the Yellow Crane Tower, and composed poems which are still on everybody’s lips today. The verse of Tang Dynasty poet Cui Hao 崔颢 provides one example (translated by Peter Harris) :

Long ago someone rode away on a yellow crane;

All that’s left here, pointlessly, is Yellow Crane Tower.

Once a yellow crane has gone it won’t come back again –

The white clouds will be empty, endless, for a thousand year.

Across the river in the sun are the trees of Hanyang in rows,

And scented grass on Parrot Island growing thick and lush.

But whereabout is my home village, in the evening light?

Seeing the misty waves on the river I grow disconsolate.

Other renowned authors include Cui Hao’s contemporary, the poet Li Bai, the national hero General Yue Fei from Song Dynasty, and Chairman Mao Zedong. These literary and artistic works had transformed the Yellow Crane Tower into a cultural symbol of Wuhan and even China as a whole.

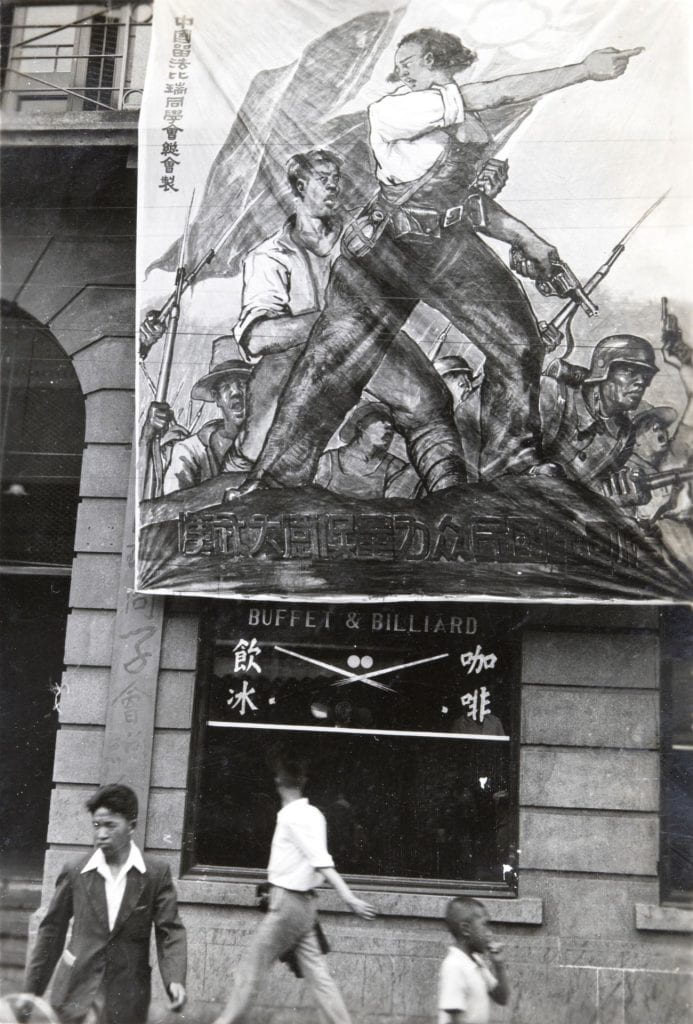

During the second Sino-Japanese War, Wuhan became the centre of Chinese resistance between 1937 and 1938, as the Nationalist government and people from the Japanese occupied areas took refugee there. In these days, the Yellow Crane Tower was the centre of China’s war mobilization effort. In front of it, politician’s speeches were given, demonstrators were assembled, battlefield news was broadcast, and ‘anti-Japanese’ murals were painted on the walls.

An anti-Japanese banner, Wuhan, 1938, during the Sino-Japanese War. Historical Photographs of China ref: Bi-s162.

After the fall of Wuhan, peculiarly, the Yellow Crane Tower was protected by the Japanese Imperial Army and its puppet Wuhan municipal government. It was lauded as the symbol of the shared culture of China and Japan, and the ‘Greater East Asian Prosperity Sphere’. As Tang Dynasty poems were beloved by the Japanese for centuries, the Yellow Crane Tower was well-known in Japan; and thanks to the travel notes of Wuhan written by Japanese writers from the Meiji Restoration onwards, Japanese people were further fascinated by it. Nevertheless, for the war-torn Chinese people who never yield to neither the cultural hegemony nor the military strength of imperial Japan, the Yellow Crane Tower had nothing to do with Japan at all. Imperial Japan’s plan of changing the symbolic meaning of the tower eventually failed.

Due to the coronavirus outbreak, Wuhan is suffering a different, but equally serious war at the moment. We despair at hearing bad news and tragedies daily, but at the same time, we are also touched by many other stories showing the glory of human nature. For instance, a Tang Dynasty verse was written on parcels of medical supplies donated by Japan: ⼭川异域 风⽉同天 (Although the mountains and rivers are different, we share the same wind and moon). Most Chinese people are moved by the beauty of the language and the heart of their neighbours in the East. This kind of human nature – compassion and selfless assistance to those in need – can definitely serve the Sino-Japanese friendship much better than the ‘constructed’ Yellow Crane Tower.

Finally, the Yellow Crane Tower has experienced and overcome countless difficulties in its history. Just as with this long-surviving landmark, we’re sure that, with the resilience of Wuhan people and the assistance from their compatriots and the international society, Wuhan will resist the virus heroically and recover from this disaster soon.

Reference: Zhao Huang, ‘Reconstruction of Power Around Yellow Crane Tower during the War of Resistance Against Japan’, Urban History Research 2017 (2) 赵煌 : ‘抗战时期中⽇围绕黄鹤楼的 记忆之争与权⼒重构’, <城市史研究>2017 (2).