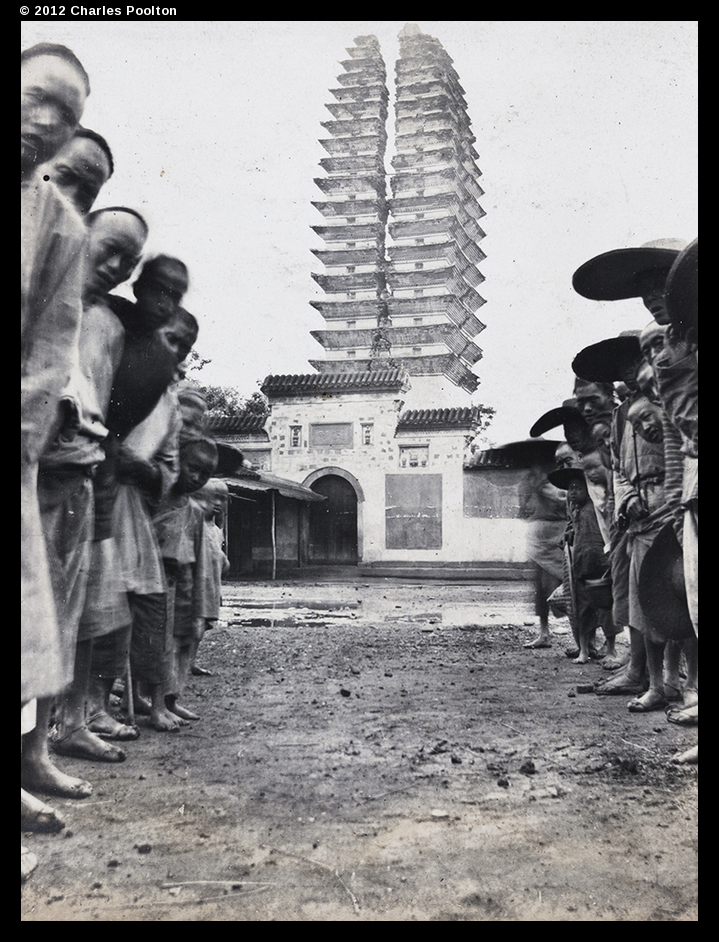

Cracked pagoda: Oliver Hulme collection, OH02-27, © 2012 Charles Poolton.

A guest blog from Dr Tehyun Ma: This rather magical photo, taken by postal official Oliver Hulme around the turn of the century, is one of my favourites.

Looking at the structure, which was probably in the vicinity of Hebei, you can’t help but be struck by a sense of the supernatural: that perhaps it was the presence of these peasants, lined up in an almost ritualistic fashion, that’s holding up this holy and ancient edifice, after it had been mortally wounded by an earthquake. And maybe – just maybe – their devotion could also make it heal … just like Xian’s Little Wild Goose.

The Little Wild Goose Pagoda, built in the eighth century, suffered a similar calamity at some point in its long lifetime: a long crack down its spine which went unattended until the 1960s. Since its completion, Little Wild Goose has not only withstood more than 70 earthquakes over 4.0 magitude, but has also healed itself time and time again. The crack, legends have it, becomes smaller to the point of disappearing until the next big quake, when the cycle restarts. Healing lore of this kind also surround Dali’s Three Pagodas and others pagoda of this style in the region.

Though the veracity of the pagoda’s self-healing powers remains unconfirmed, the ability of some split pagodas to withstand collapse has intrigued scientists. The long-standing theory of a wok-base foundation, which some suggest gave the structure a ‘Budaowen’ (or roly-poly) quality, has recently given way to a new hypothesis about the ‘stepped’ or stair-like foundation. This building technique, drawn from old Chinese tomb construction, lessens the impact of the quakes and may allow the two halves of the structure to collapse gently back onto each other.

This particular pagoda was not so fortunate. Attempts to track down its precise location have thus far drawn a blank, and at some point, it seems likely that it collapsed without being rebuilt. We’d be keen to hear from anyone who might be able to help identify it.

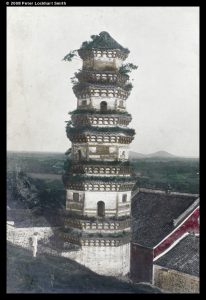

UPDATE November 2013, Mystery solved: In Spring 1913 American Luther Knight (1879-1913) took at least two photographs of the pagoda, which are reproduced (without the mesmerising audience) in Looking back at Chengdu: Through the Lens of an American Photographer in the early Twentieth Century (回眸历史:20世纪初一个美国人镜头中的成都), just published by China Travel and Tourism Press. The site was the Longxing Temple, in Pengxian county (now Pengzhou city, north of Chengdu), Sichuan province (四川省彭县城龙兴寺) and –magically the pagoda, much altered, still stands.