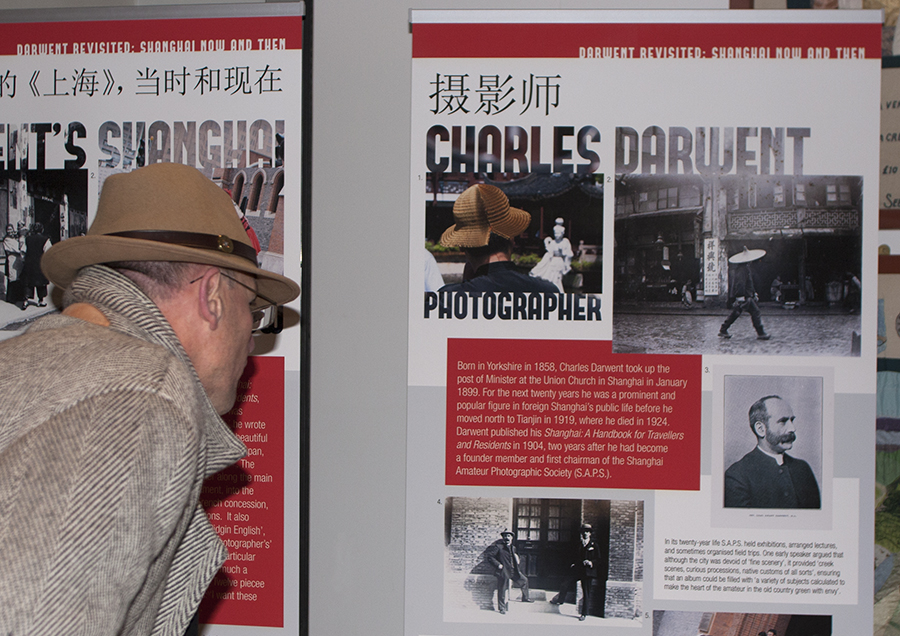

Photography is the context, subtext and pretext for an exhibition that opens today. The exhibition includes new photographs by Jamie Carstairs inspired by the text of Shanghai: A Handbook for Travellers and Residents, a guidebook to the city by Revd. Charles Darwent, first published in 1904.

Darwent was a Minister at the Union Church in Shanghai, and a founder member and first chairman of the Shanghai Amateur Photographic Society (S.A.P.S.). His guidebook includes useful phrases in ‘Pidgin English’, including some for use ‘At a Photographer’s’ which hint at the guide book’s particular flavour, for this book was very much a photographer’s companion. ‘Twelve pieces wanchee wallop’, it begins: ‘I want these twelve plates developing’.

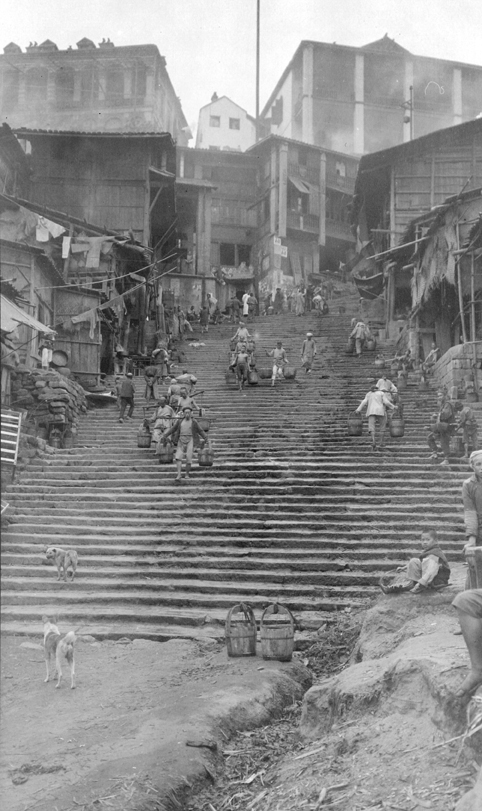

Serendipity brought a carefully annotated album of Darwent’s original photographs to the ‘Historical Photographs of China’ team in 2009, and many of the prints were originals of those reproduced in his guide. In 2011, inspired by the album, photographer Jamie Carstairs set off to revisit Darwent’s Shanghai, following Darwent’s guidebook instructions, and seeking to recapture the spirit of the book.

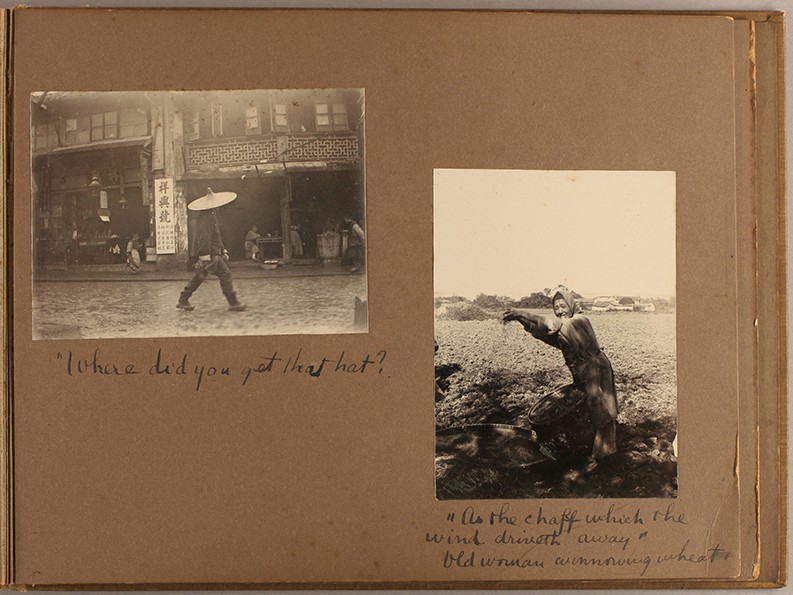

Like the Brazilian photographer Sebastiao Salgado, the words of the Bible must have been the ‘soundtrack of Darwent’s life’ – it is marvellous that some of his original photographs have survived, for time is not kind to pieces of photographic paper “As the chaff which the wind driveth away” (Psalms 1:4, King James Bible ‘Authorised version’. In his album, Darwent captioned his photograph of a woman winnowing wheat with this biblical quotation – see below).

Darwent Revisited: Shanghai now and then is part of the University of Bristol’s InsideArts festival and was funded by the AHRC and the British Academy. The exhibition features photographs by Jamie Carstairs, Charles Darwent and other images from the Historical Photographs of China collections. It is on at The Island, Bridewell Street, Bristol BS1 2LE, until Friday 22nd November, 10am to 6pm.

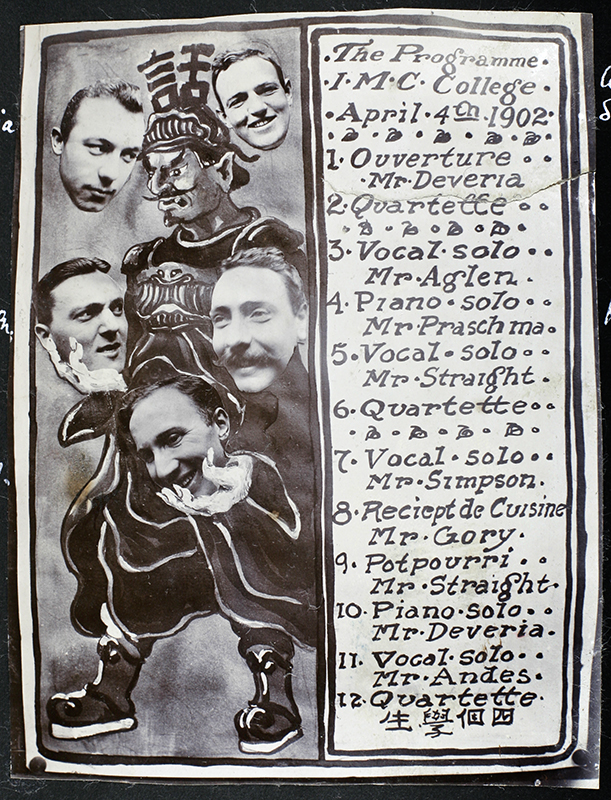

A page from an album of photographs given by Revd. Charles Darwent to H. Wilcockson.

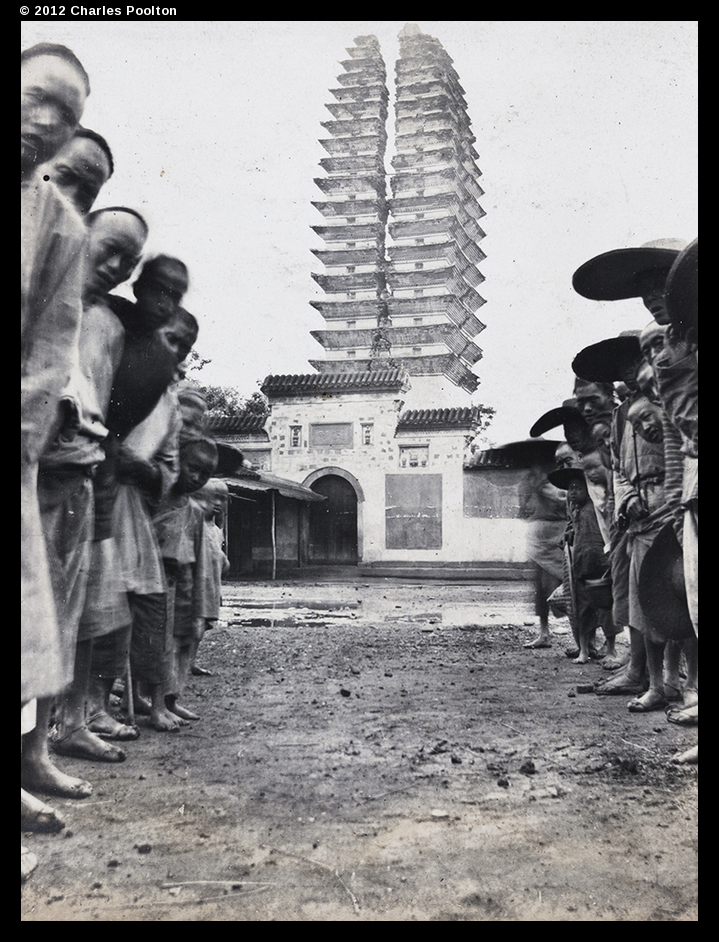

‘Where did you get that hat?’ Photographs by Charles Darwent. © 2009 Jane Hayward.