Our guest writer today is Nadine Attewell, Associate Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies atSimon Fraser University, and director of the undergraduate program in Global Asia. She is the author of Better Britons: Reproduction, National Identity, and the Afterlife of Empire (2014), and is currently at work on a second book entitled Archives of Intimacy: Racial Mixing and Asian Lives in the Colonial Port City.

Hong Kong Aida Rosie Weiwing-lox(?) Annie’ng(?) Ssǔ-hing(?) R.F.C.H. A. Gardiner: R.F.C. Hedgland Collection He02-017 © 2007 SOAS

Taken in the aftermath of some sumptuous meal, the photograph is badly cropped and over-exposed. Of the people in it, only one, the Chinese woman leaning forward with her head in her hand, emerges with any clarity: she looks pensive, or perhaps bored. The clean-shaven white man who can just barely be seen around the other side of the table, hand casually draped over his neighbour’s shoulder, is Chinese Maritime Customs employee Reginald Hedgeland, who preserved the photograph for posterity. According to the caption, which dates the photograph to 1920, the dinner took place in Hong Kong, where Hedgeland often traveled for work and pleasure from his post in Nanning. Hedgeland recedes into the background of the photograph, and he is likewise not my focus here. In my work on Chinese practices of interracial intimacy and multiracial community under British colonial rule, photographs have consistently opened up perspectives not usually prioritized by the colonial archive. This photograph functions similarly: I have learned so much through allowing myself to wonder about the Chinese women who feature in it.

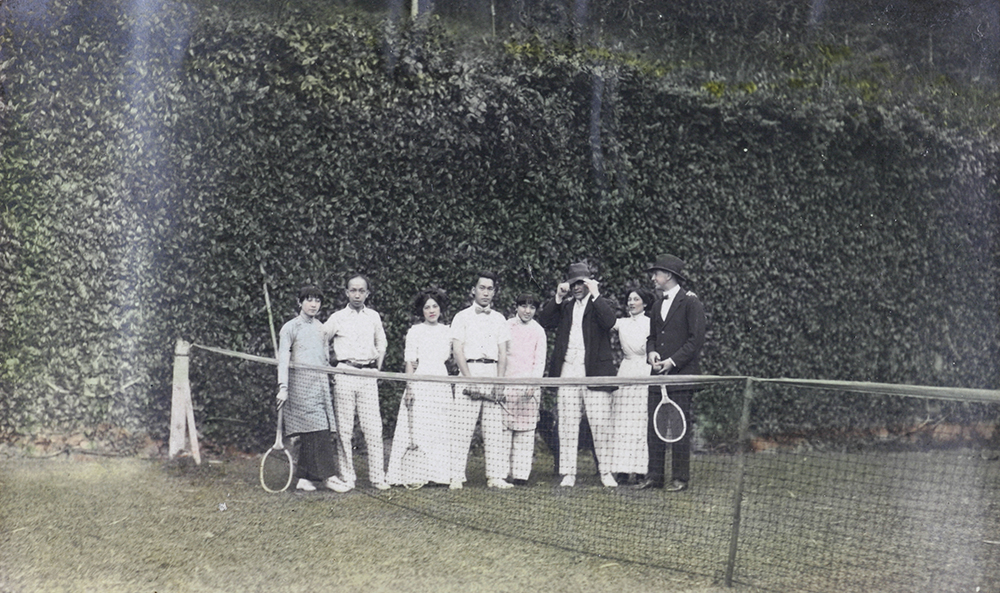

Tennis at Hong Kong, Oct., 1920. Annie / Aida / Rosie / Weiwing-Lox / R.F.C.H. / Barbara / Mr. Chan / Sir William Shenton: R.F.C. Hedgland Collection He02-018 © 2007 SOAS

Although Hedgeland did not usually identify his Chinese photographic subjects, the wealthy men and women with whom he socialized in Hong Kong are another story. Hedgeland’s captions tell us that he was joined at dinner by A. F. Gardiner, banker and tennis star Wei Wing-lok, Wei’s wife Annie (née Ng Quinn), and her sisters Ada and Rosie. Annie, Ada, Rosie, and Wei also feature in another of Hedgeland’s photographs, of a tennis party Hedgeland attended during the same trip. As the son of Wei Yuk, a businessmen who served on Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, Wei Wing-lok was born into the ranks of Hong Kong’s Chinese élite. Unlike his British-educated father, however, Wing-lok studied engineering at MIT, joining a cadre of American-educated ethnic Chinese men born in and around the Pacific who played important roles in early-twentieth-century Chinese politics and economic development, like Ada Ng Quinn’s engineer husband Morrison Yung; Rosie Ng Quinn’s husband Bang How, who was friends with Mei-ling and T. V. Soong; and Bang How’s brother-in-law (and future Chinese finance minister) Huang Han-liang.[1]

I tracked down much of this information on websites devoted to genealogical research and university alumni history; as well as in recent scholarship about Chinese students and their transpacific itineraries. In this way, the photographs reward a methodology that attends to the intersections between the archives of (informal) empire and Chinese migration. But they also unsettle the androcentrism of such materials and accounts. I haven’t been able to learn much about the educational careers or professional aspirations of the Chinese Australian Ng Quinn sisters, who linked Wei Wing-lok, Morrison Yung, and Huang Han-liang as kin. Nevertheless, the looks, touches, and convivial fixtures that animate photographs like Hedgeland’s testify to their relational labour (and that of the absented staff on whom they relied). As one of my graduate students recently observed, the genealogical gossip historians encounter in the archive isn’t just a source of useful information about people in the past; it is also a trace of the gendered, racialized, and classed labour of social reproduction.[2]

Certainly, genealogical gossip can work to shore up heteropatriarchical power. Still, we shouldn’t assume that the relation work of élite women like the Ng Quinns always served the interests of their male kin, or of the white men who came to their homes to be entertained. In the photograph of the tennis party, the woman on the right side-eyes the camera, lips parted, posture confident, her arms stretched casually, almost possessively, around Hedgeland and his companion. This could be the “Barbara” Hedgeland names in his caption, but I want to explore another possibility. Around this time, the eldest Ng Quinn sister, Violet Lucy Chan, moved into a large house on Po Shan Road with extensive grounds that could well have accommodated a lawn tennis match or two. Violet’s life trajectory followed that of her sisters, at least up to a point. Like them, she married into a transpacific Chinese family, the Chans (or Chuns) of Hawai‘i, who accumulated enormous wealth and political power in both Hawai‘i and Guangdong, where Violet’s husband’s uncle Chun Chik-yu briefly served as governor.[3] During the 1910s, however, she left Chan and re-established herself in Hong Kong as a vibrant figure about town. In his autobiography, Percy Chen, the son of Sun Yat-sen’s Chinese Trinidadian ally Eugene Chen, recalls Violet Chan regularly holding court at the Hong Kong Hotel during the 1930s, when he worked as a barrister in the colony.[4] Might Violet Chan have hosted the tennis party? Could she be the woman Hedgeland identifies as “Barbara”?

According to Violet’s great-nephew Michael Ng-Quinn, after the breakdown of her marriage, Violet became intimately involved with a British lawyer who sponsored not only her lavish residence but her younger brother Sydney’s entry into the legal profession as well.[5] Whatever the truth of this piece of genealogical gossip, she appears to have been close to British solicitor George Hall Brutton, who was Sydney’s employer when he qualified as a solicitor in 1935[6]: in 1943, British intelligence sources reported that Brutton had been released from the civilian internment camp at Stanley – on guarantees provided by one Violet Chan.[7] The intelligence report containing this nugget jocularly describes Violet as “Auntie V of ARP fame,” a reference to her role in Wing-Commander Horace Steele-Perkins’s colony-wide plans for air-raid precautions, which became mired in allegations of corruption. During a public enquiry in late 1941, Steele-Perkins explained that he and his wife had recruited Violet, whom he visited regularly at 6 Po Shan Road, to assist with ARP outreach amongst Chinese Hong Kongers.[8] Although Steele-Perkins’s relationship with Mrs. Chan attracted less salacious attention than some of his other entanglements, it was tarred with the same insinuating brush.

Violet’s relationships with men like Brutton or Steele-Perkins may or may not have adhered to norms of respectable Chinese femininity; neither she nor her sisters need rescuing from such insinuations and the expectations that undergirded them, which they likely also confronted in everyday life. What matters is that Violet found ways of using such relationships to pursue the projects that mattered to her – and vice versa. Her kin remember Auntie Vi with appreciation, testifying to the care that her wealth and connections enabled her to provide for them, including during the Second World War, when several of Violet’s siblings and their children took shelter at the property on Po Shan Road.[9] After the war, recalls Michael Ng-Quinn, she permitted refugees from the Chinese mainland to settle there too.

My account here is speculative. Still, the broader point stands: how would our accounts of early-twentieth-century Chinese social and political landscapes change if we attended to the labour not just of white men (like Hedgeland), entrepreneurial Chinese middlemen (like Wei Yuk), or their credentialed sons (like Wei Wing-lok), but of the Asian women, including amahs, mistresses, and sex workers as well as wives, aunties, sisters, and daughters, alongside whom they lived, worked, and played? What political possibilities might inhere in Rosie Ng Quinn’s bored, offstage stare or the jaunty confidence of “Barbara’s” embrace?

[1] For more on the connections between the Ng Quinn, Bang, and Huang families, including a photograph of Rosie’s wedding to Bang How, see https://www.huangquest.com/marriage-to-mo-li-how.html.

[2] I am grateful to Adrianna Michell for her thoughtful reflections on genealogical gossip, a term used by Esselyn/Chumash writer Deborah Miranda in her family memoir Bad Indians (Heyday, 2013), 67.

[3] For more on Violet’s marriage to Chun Wing-on, see Robert Dye, “Merchant Prince: Chun Afong in Hawai‘i, 1849-90,” Chinese America: History & Perspectives (2010): 33.

[4] Percy Chen, China Called Me: My Life Inside the Chinese Revolution (Little, Brown, 1979), 277.

[5] Interview with Michael Ng-Quinn, September – November 2010, sponsored by the Research and Educational Center for China Studies and Cross Taiwan-Strait Relations, Department of Political Science, National Taiwan University, http://www.china-studies.taipei/act02.php.

[6] “New Local Solicitor: Mr. Sydney Ng Quinn,” Hongkong Telegraph, August 23 1936.

[7] Kweilin Intelligence Report No. 27, December 30 1943, PR82/068 Box 10 Folder 7, Lindsay Tasman Ride Collection, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

[8] “Queries on Construction of Stores for ARP Dept.,” Hongkong Telegraph, September 30 1941.

[9] Loretta NgQuinn Slaton, We Walked to Freedom (iUniverse, 2007), 3-5; interview with Michael Ng-Quinn.