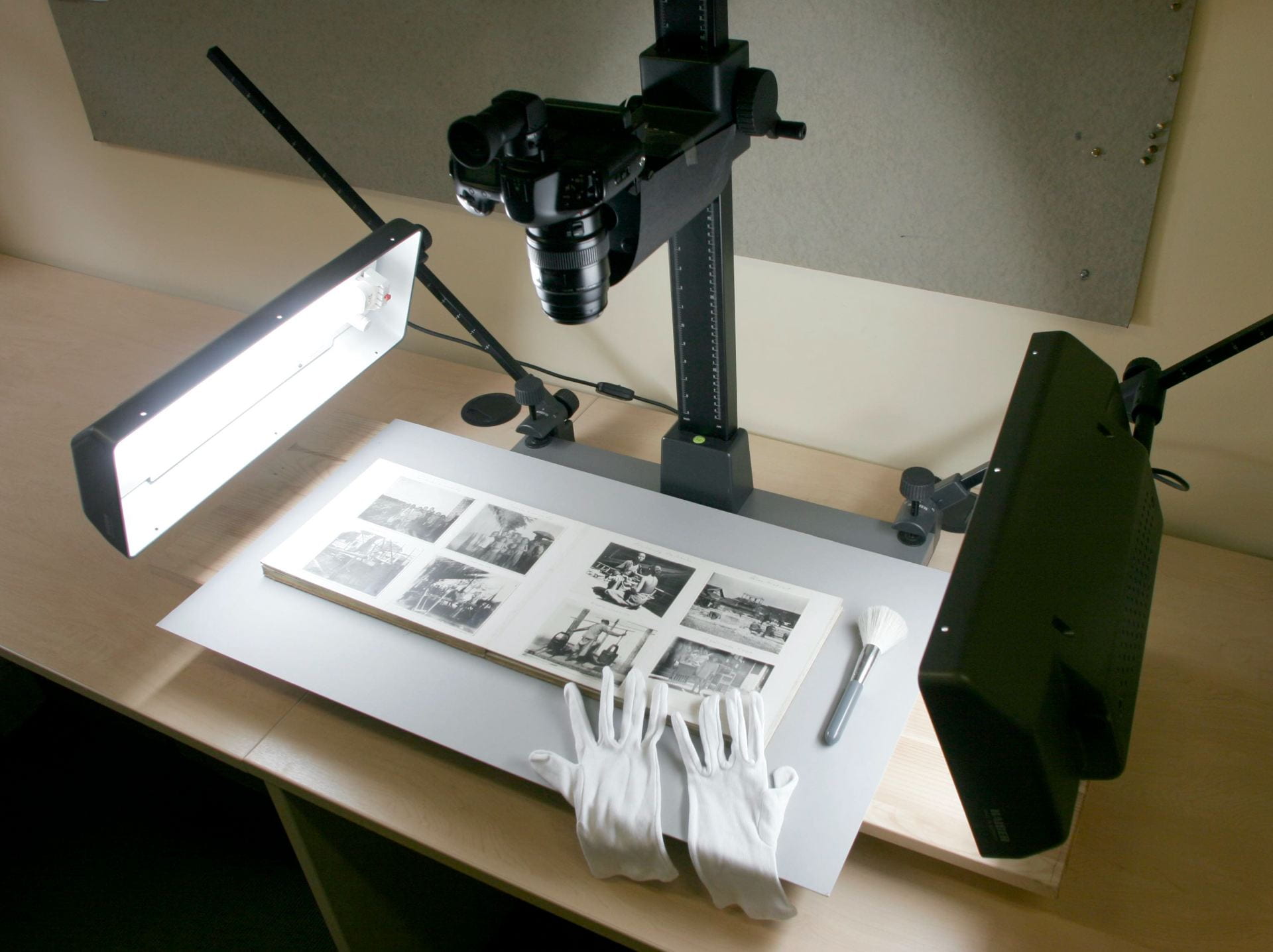

It is 15 years since the launch of Historical Photographs of China. In that decade and a half we have copied about 170 mostly privately-held collections of photographs, which has generated just over 62,000 unique images in our databank, and published over 22,000 of them on our platform (and its mirror site in China), under a Creative Commons license which allows non-commercial reuse (with attribution). While something like 7000 came to us digitally, in the main we have taken loose prints, photograph albums, negatives, magic lantern slides, real photo postcards and transparencies (35mm slides), ranging in date from the late 1850s to the late 1960s, and copied them here in Bristol, or on site.

In recent months we have been preparing our digital holdings for transfer into the University of Bristol’s new Digital Assets Management System (DAMS), which will ensure very long term preservation of these records of China’s history. This has always been our long-term goal.

Fifteen years is a very long time for a standalone project to run, and the time has now come for a change. Although we have over that period been awarded something like half a million pounds of funding from a range of public and private sponsors – the British Academy, AHRC, ESRC, JISC, Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation, John Swire & Sons – as well as a great deal of tangible in-kind support from the University of Bristol (not least the DAMS), it has never been easy to secure funding for a resource-building project like this.

From this month onwards, as our digital holdings are moved into the DAMS, which is hosted within the University Library’s Special Collections and Archives, ‘Historical Photographs of China’ has become one amongst other notable individual collections held within Special Collections. It will no longer have that separate identity as an active project, and will no longer be looking for new materials to digitize. The project has ended, but the collection will last.

My key ‘asset’ as project director has always been the project’s manager, Jamie Carstairs, who joined it in February 2006, and who has himself copied the greater part of our collection, added and checked a great deal of metadata, arranged the collection and return of materials, handled requests for publication and reuse, and spotted coincidences and connections across the materials (most wonderfully the fact that we had two photographers who actually stood side by side as they photographed the same group, and that we had shots across three separate collections of an impromptu football kickabout in the Jiangsu countryside). Jamie has over that period been supported by, in particular, Shannon Smith, and Alejandro Acin, and by others who worked on discrete collections or initiatives, by colleagues in the University of Bristol’s Research IT team who have worked our platform, and by Christian Henriot and Gerald Foliot who first provided a home for the project ‘in’ France.

Jamie has now moved to join the library’s Special Collections team full time, working on that team’s work. When time allows, we hope to publish new collections from our backlog, and some work continues on creating metadata for our unpublished holdings to support this. Queries about reuse of project materials will now be handled through the Special Collections mailbox. Over the years we have had several collections of original material donated to us, and these have been transferred from the project to Special Collections, and this remains an option for those who might be wishing to find a long-term home for such materials.

Green boxes of HPC materials in the Special Collections stacks, University of Bristol Arts and Social Sciences Library

As director, I am immensely grateful to Jamie for his work across the past decade and a half, which has taken him across the country, and of course to China, and during which he has learned a great deal more about the historical cityscapes and landscapes of China than he ever expected to back in 2006. Give Jamie an uncaptioned photograph of a bridge in Sichuan, and likely as not he’ll know where it is, or where to look to confirm a hunch. Without Jamie, none of what the project has achieved would have been possible, and that also includes our own exhibitions in London, Bristol, Bath and Durham, Nanjing, Chongqing, and Beijing, and contributions to other exhibitions and museum collections across China and Hong Kong, as well as our own publications — including this blog.

I am of course hugely grateful to all those who allowed us to copy their albums and photographs and to share them with the world. Mostly, people have proactively sought us out, having heard about us by word of mouth or having listened to the BBC Radio 4 programme about the project, or who have found us through internet searches. This is very much a project that has thrived because of the generosity and kindness of our community of donors, who have entrusted us with their albums and documents. We have had material sent to us from Asia, Australia, north America, the European continent, and of course from across Britain. In addition we have benefitted from partnerships with SOAS, the Cadbury Research Library (University of Birmingham), The National Archives, John Swire & Sons Ltd, the Needham Research Institute, Special Collections and Archives at Queen’s University Belfast, the Bath Royal Literary & Scientific Institute, and Harvard-Yenching Library: these have helped enrich the collections enormously.

I am also grateful for the warm support (and corrections, and other details) that we have received from supporters of our work, which we know is widely used in teaching and in research presentations, and which has an audience of researchers, learners, family historians and the simply just interested, across the globe, and to colleagues at the University of Bristol (including the Dean who, in 2006, asked, ‘so, there are a lot of photographs out there: when will you know when to stop’). We are currently in the midst of refreshing the platform itself (for technical reasons due to the looming end of life of its underlying software) but it will not be vanishing, and we hope in the not-too-distant future to be able to publish a wonderful collection from a family who lived and worked in Hong Kong and in Shanghai, and a little later something quite different: a large collection from the heart of revolutionary China during the Second World War. More on those anon.

In the meantime, many thanks again for all your support, and please, keep using the photographs: that’s what they’re there for.

Robert Bickers

Director, Historical Photographs of China project

Fu Bingchang, with camera: Fu Bingchang Collection Fu-n174 © 2007 C. H. Foo and Y. W. Foo

As the caption says, that’s Fu Bingchang, whose photography has kept us busy: we copied some 2,500 photographs he took in China, the USSR (when ambassador there), and western Europe, with some 550 available on HPC. This was one of the early collections that we copied.