Our latest post is from Sarah Yu, a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Pennsylvania. She is writing her dissertation on hygiene and daily life in Republican China. You can see some of the archival highlights of her research on her blog site, Chinese Must Wash Their Hands Before Returning To Work.

While we do not often associate Republican China with much political cohesion, Chinese people were actually united throughout much of the early twentieth century in their ongoing war against the humble house fly. Cholera – the disease most intimately linked to the filth of the common fly – tangoed with its vector in water sources, kitchens, and toilets. Naturally, these spaces became the earliest targets of some authorities’ sanitation measures. The Shanghai Municipal Council had established the practice of conducting regular inspections of slaughterhouses and market stalls before the turn of the century, and completed a new ‘state-of-the-art’ water supply and sewage system by 1883.[1] In addition, the Municipal Council’s Nuisance Department, established in 1867, employed street cleaners who would clear the public streets of night soil and waste and sell the former to local farmers for fertiliser.[2] Cholera education campaigns, often large-scale parades through city streets demonstrating effective fly traps and sanitary cooking methods often also provided onlookers with combined cholera and typhoid vaccinations.

Chinese woman being inoculated in the street, Shanghai, c.1937. Photograph by Malcolm Rosholt. HPC ref: Ro-n0781.

My recent research on Republican hygiene education has led me to investigate the proliferation of ‘fly elimination campaigns’: group efforts launched by cities, schools, and other communities that required mass participation to kill as many flies as possible. The goal of these campaigns was ostensibly to curb outbreaks of gastrointestinal disease – something needed to be done to eliminate those fatal flying pests that could bring a swift death almost silently, to anyone.

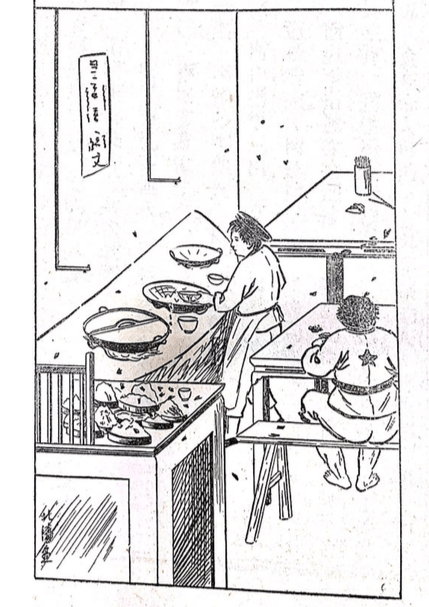

“Cooking food can kill germs, but flies can still come to infect uncovered, cooked food.” Source: “Weisheng Tushu [Health-Picture Talks]”, Council on Health Education References Books no. 32 (Shanghai, Kunshan Garden no. 4), n.d. Yale University Countway Library of Medicine (New Haven, CT).

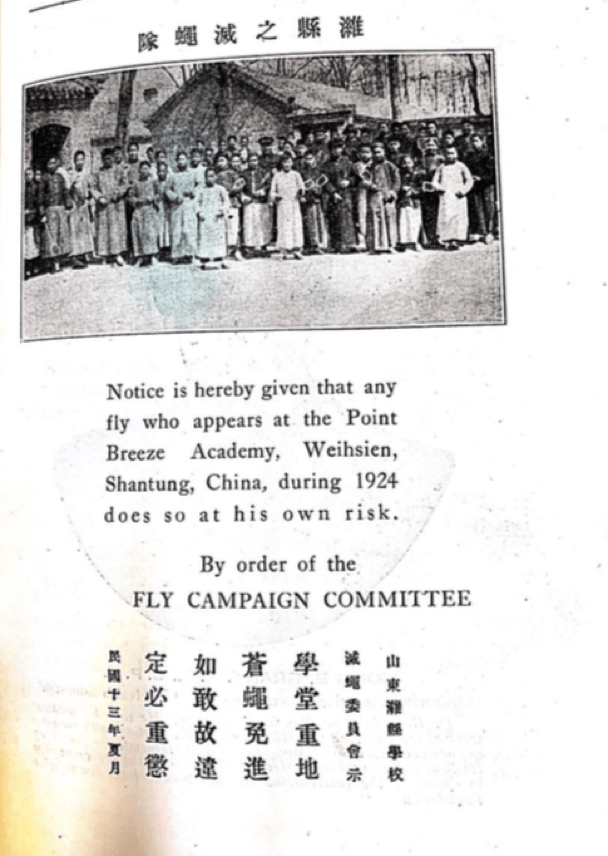

Fly Campaign Committee notice. Source: Health 1, no. 1 (Shanghai: YMCA Press, 1924).

Throughout Republican China, fly elimination campaigns quickly became a norm for cities, schools and workplaces, even more so as China headed into war. Flies had been a national enemy for all the unsanitary havoc they had unleashed on the Chinese people, but now there was another urgent enemy – the Japanese.

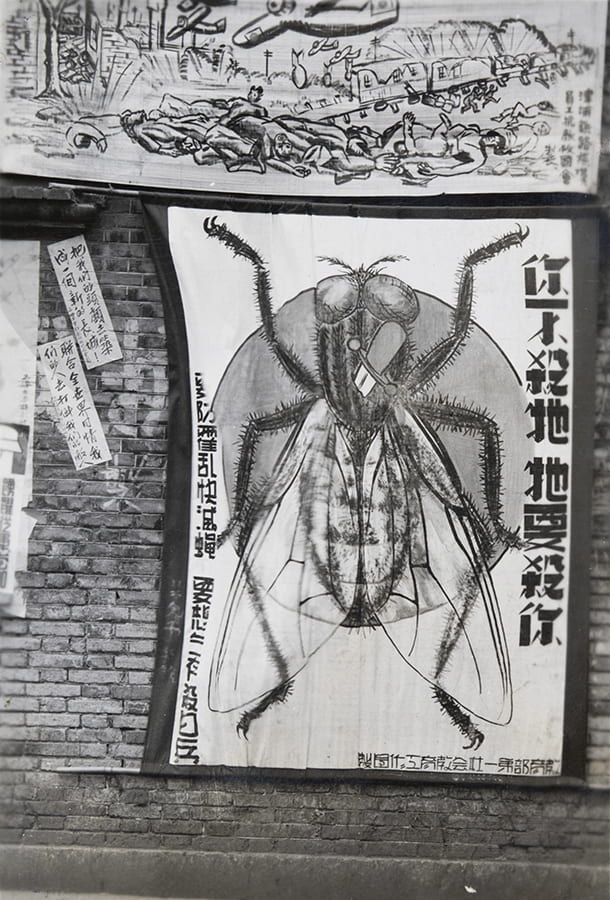

Posters, like the one above, creatively ensured that viewers’ fears of both flies and the Japanese were top of mind, and intertwined. This one depicts a fly with a Japanese Rising Sun emblem, with slogans on the side reading ‘If you don’t kill it, it will kill you … we need to prevent cholera and kill flies: and if you want to survive, kill the Japanese soldiers’. In another image, a fly is depicted as a fighter jet that drops bombs labelled ‘cholera’ onto a crowd of people. Numerous other flies are lined up behind the first.[6] Chongqing’s population, already sensitive to bombing attacks from Japanese forces, were now presented with a picture of two missiles heading towards a populated city, with the caption ‘Air raids are scary, cholera is more scary!’.[7]

While cholera prevention rarely makes headlines anymore, efforts against other epidemic disease still do. Some reforms still eerily resonate with their historical counterparts. As early as the 1910s, representatives from the Rockefeller Foundation reported that China’s mines and industrial sites should consider implementing 50-foot-deep bore-hole ‘Java style latrines’ for better prevention of cholera and hookworm infections. China watchers today may find it interesting to read the intermittent news reports about Xi Jinping’s ‘toilet revolution’ – a national initiative to improve the overall sanitation levels of facilities in tourist destinations and cities around the country. Since its launch in 2015, the central government has spent over 21 billion yuan to clean, refurbish, and rebuild over 68,000 bathrooms. But the campaign has left the country with some unexpected, and some undesired, results. Caixin also reported that even in 2019, villages were still unsure about how the funding from the central government would be distributed to pay for individual toilets.

Moreover, if toilet reform began explicitly in order to manage the control of epidemic diseases, it has proven to be insufficient for the most recent outbreaks of COVID-19. The physical toilet itself, just like the physical extermination of a few (or even 12 million) flies, is only one link in the long chain of actions for health improvement that need to be performed by different levels of government and their constituents, from sewer updates, waste management, diligent restocking of toilet paper/hand soap/cleaning supplies, to individual toilet users’ personal behaviours. An air-conditioned, glass-roofed toilet may inspire, but certainly not compel, its user to aim, flush, and properly wash hands, that some well-placed spittoons will redirect phlegm from the sidewalks and into appropriate receptacles, or even that more, accessible hospitals will lead to more people getting regular health check-ups.

The distance between infrastructure progress and individual responsibility was, and remains, a significant barrier to public health improvement. In fact, Republican China’s continued war against the humble fly was really a series of efforts to knock down this barrier. The famed example of Qiaotou Village’s fly extermination campaign in 1934, published in multiple book series including the Commercial Press’ Xiaoxuesheng Wenku, is a perfect illustration. In this small but accessible village near Shanghai, students at a local school started a fly killing campaign to address the fact that local residents did not feel safe from disease. ‘There is a child in America who has caught 121,000 flies! And there are other cities in which people don’t see any flies. Let’s make this happen here too!’ The team promoted its proposal to kill then feed the flies to livestock to keep them plump, and then to secure enough fly swatters and traps for all participants. The students on the committee were directors, promoters, and suppliers of cleaning products; the participants included many of their elders – ‘farmers, workers, businessmen, and old women’. While an elderly man dismissed the seriousness of the campaign at its start, saying ‘we can now live more than seventy years, which would be impossible if flies and mosquitoes really were so harmful’, by the campaign’s end, no villager could deny that flies were dangerous enemies and capable murderers.

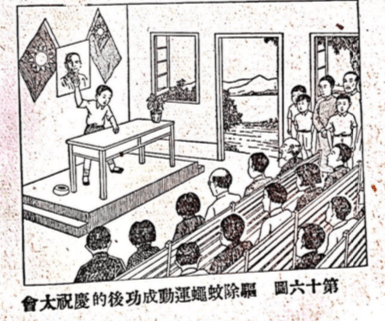

‘Meeting to celebrate the success of the Fly-Elimination Campaign’. Source: ‘Quchu Wencang Yundong [Fly-Elimination Campaign]’, Xiaoxuesheng Wenku (Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1934).

The idea for fly elimination started from the mind of a precocious schoolchild, who then explained the rational, tangible benefits of his proposed campaign, and successfully led the wider community towards solving the problem. Just as a single student could start a campaign that would change the minds of hundreds in Qiaotou, every Chinese person could start from killing a few flies to make progress, and every individual living in a COVID-19 pandemic world can begin by wearing a mask or washing his or her hands.

[1] Isabella Jackson, Shaping Modern Shanghai: Colonialism in China’s Global City (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 167—8.

[2] Yu Xinzhong, ‘The Treatment of Night Soil and Waste in Modern China’, in Angela Leung and Charlotte Furth (eds.), Health and Hygiene in Chinese East Asia: Policies and Publics in the Long Twentieth Century (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011)

[3] John B. Grant, ‘Fly and Mosquito Control in Nanjing’, 19 January 1924. Folder 348/Box 55/FA115, Series 601, RG 5, IHD, Rockefeller Archive Center (Sleepy Hollow, NY).

[4] ‘Guoli di erishier zhongxuexiao ben bu ji yi er liang fenxiao zhengjie shishi qingxing [cleanliness of the 22nd middle school and two affiliate schools]’, March 1943, Second Historical Archives of China 5/1927 (2) (Nanjing, China).

[5] John B. Grant, ‘Report of the Peking First Health Station for 1930’, 30 September 1930. Folder 471/Box 67/FA065. CMB Inc, Rockefeller Archive Center (Sleepy Hollow, NY).

[6] ‘Weishengshu yifang bibao [posters about medicine and defence]’, Kuomintang Party Archives 502/90 (Taipei, Taiwan).

[7] ‘Jiaoyubu guan yu gaohao qingjie weisheng fangfan huoluan shanghan he fenfa yimiao yaopin yu geji xuexao waiwenshu [Ministry of Education communications with various schools regarding sending cholera and typhoid medications and hygiene work]’, 1943. SHAC 5/1925(1) (Nanjing, China).

[8] ‘Quchu Wencang Yundong [Fly-Elimination Campaign]’, Xiaoxuesheng Wenku (Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1934).