James Carter is the author of the forthcoming Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai (W.W. Norton), which uses the events of 12 November 1941 at the Shanghai Race Club to tell the story of China on the eve of World War II. He has written two previous books on Chinese history, and contributed to the Times Literary Supplement, the LA Review of Books, ChinaFile, and the Washington Post Monkey Cage blog, among other venues. He is Professor of History and Director of the Nealis Program in Asian Studies at Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, USA.

Covid19 has fueled a fascination with apocalypses. The end of fictional worlds dominate our media choices: Contagion, 2012, Train to Busan, Deep Impact … we can fill our socially isolated nights with demise of worlds that never were. But worlds end all the time, and not just in fiction, and perhaps it is a good time to look back at some one of them. Historical Photographs of China provides us glimpses of what those moments of impending doom.

Perched at what seems like the end — if not the end of the world, at least the end of the world we have been living in up to now — I’m thrown back to think about when worlds ended before.

I’ve been immersed for some time in Shanghai as it toppled into World War II. I focused my research on a single day — Champions Day, 12 November 1941 — chosen precisely because it was on the margins between one world — old Shanghai, with all its cosmopolitanism and cruelty — and what would follow. It would not re-emerge, at least not as it had been.

Shanghai had existed as unique enclave since the 1840s. It looked like a colony, swam like a colony, and quacked like a colony … but officially, at least, it was not a colony. The International Settlement and French Concession, though, were unique spaces, insulated from most of the trials that swept across China in the last decades of the Qing dynasty, a revolution that overthrew it, and the turmoil that followed.

By the 1930s, the autonomy of these concessions was well established, but their future was increasingly hazy. The 1932 ‘Shanghai War,’ sparked by nationalist tensions and the death of a Japanese monk, killed more than 10,000 people in and around the city as Japanese and Chinese forces fought one another. For the ‘Shanghailanders’ — white (mainly British) inhabitants of the International Settlement — the fighting caused concern, but little real disruption to their lives. Consideration was even given to postponing Champions Day, the holiday in the Settlement when life paused for the running of the Champions’ Stakes, and crowds of 20,000 or more would see one of the city’s fastest horses crowned ‘King of the Turf,’ but in the end, a delay was not necessary. A ceasefire took hold in March, and life in Shanghai quickly recovered. Even the city’s two Chinese-owned and operated racetracks, which had been damaged in the fighting, quickly re-opened and began hosting races once again. Shanghai had survived the end of the world … for now.

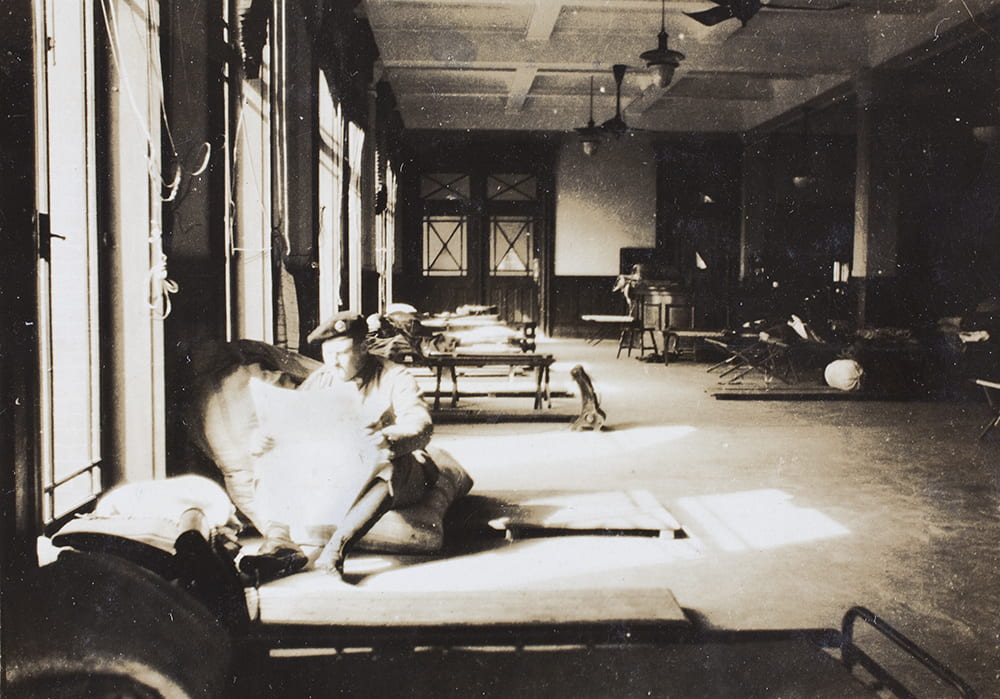

Shanghai Volunteer Corps billet in Racecourse grandstand, Shanghai, 1932. Photograph attributed to Jack Ephgrave. HPC ref: Ep01-291.

The world would end again in the summer of 1937. If 1932 hinted that the world of Old Shanghai might not be permanent, 1937 shouted it. The hostilities that broke out between Japan and China at the Marco Polo Bridge near Peiping (as Peking was then officially known) in July spread to Shanghai later that summer. ‘Black’ or ‘Bloody Saturday’ — 14 August 1937 — was an accident. Chinese pilots mistakenly dropped bombs over the International Settlement, which was supposedly neutral in the conflict at the time, but the effect was no less deadly for having been inadvertent. Thousands died, including many refugees fleeing the fighting all around, and also the first Americans to die in World War II.

From 1937 on, Shanghai entered its Lone Island (gudao 孤岛) era. Japanese armies completed their occupation of the city — except for the foreign concessions — in November, and for four years, until Japanese armies marched onto the Bund on 8 December 1941, the Settlement at the heart of Shanghai clung to its autonomy. We might routinely describe the moment as liminal, poised between the world the ending and the one about to begin. I often think of it more as Wile E. Coyote, suspended in mid-air while the smoke cleared and revealed the abyss below.[1]

Though glimpses into the chasm were common in the Lone Island period, the cartoon coyote stayed somehow aloft. Scarcity and hoarding led to inflation. Foreign consulates advised their nationals to leave. Refugees found their way to the city, escaping the war that was brutalizing China (the atrocities of the ‘Rape of Nanking’ were less than 200 miles away). But amid this chaos, life in the Settlement went on.

Racing went on too—the Chinese-owned tracks were closed (destroyed, really) by the war, but the Shanghai Race Club at the city’s centre was soon drawing larger crowds than ever as Shanghai residents sought escape from the grim reality surrounding them.

It was not until December 1941 that the world ended again. The same offensive that Americans remember mainly for Pearl Harbor included Japanese attacks on Hong Kong, Manila, Singapore, and Shanghai. The Japanese strike on Shanghai was quick — sinking or seizing the two remaining Allied gunboats moored in the Huangpu River — but the fate of Shanghai was, as usual, slow to resolve. Although long apprehensive about its fate, Shanghai suffered less during the war than just about any city in Asia. Although there were a few arrests, it was eight months before a large number of Allied men were imprisoned, and another six months before most remaining Allied nationals were interned by the Japanese in euphemistically designed Civilian Assembly Centres.

Rev. Dr Forbes Scott Tocher, goats and staff, at the ‘farm’, Lunghua Civilian Assembly Centre, Shanghai, 1945. Photograph by Oscar Seepol. HPC ref: To-s27.

Even the race track stayed open, dominated still by British nationals into 1942, then controlled by Japanese interests who continued racing right into the summer of 1945. Just weeks before an atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, newspapers in Shanghai were still advertising the races.

Old Shanghai did not return. Racing did not restart after the Japanese surrender. Although the city’s architecture survived the war (much of it lasting to be destroyed as part of the city’s economic resurgence in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries), it was fundamentally changed, in ways that few people looking at the gathering clouds in 1932, or 1937, or 1941 could have predicted.

[1] Ed.: for those too young to catch this reference, follow this link.