A guest blog from Jon Chappell, who recently secured his PhD at the University of Bristol, on ‘Foreign Intervention In China: Empires And International Law In The Taiping Civil War, 1853-64’. Jon is currently working on a British Inter-university China Centre Cultural Exchange Partnership with the Transform Drug Policy Foundation, and from August will be teaching for a year at NYU Shanghai.

Sometimes the revolution is a tea party. This seemingly festive photograph represents the culmination of a radical campaign to rid China of opium. In 1906 the Qing dynasty and Britain agreed on a deal to enforce full prohibition of the drug’s use within ten years. The British would end imports of opium from British India if the Qing state could end the harvesting of opium poppies in China. Although the Qing fell in 1911, the agreement was maintained. By 1919, the last warehoused stocks of opium were being destroyed in Shanghai. This photograph, taken at the Nanning customs house, possibly records a similar event, or it may record the destruction of opium confiscated by the customs service as it was smuggled around the country. Either way, the destruction of opium was an event to be recorded, as the rows of onlookers, seated in front of the confiscated cache, suggest. In fact, the picture is a more sedate version of the opium burning celebrations held at the start of the suppression campaign.

The popular and government support for the suppression of opium was not just linked to the drug’s troubled history within the Qing empire. Although the Qing had initially resisted foreign opium imports, sparking an ‘opium’ war between Britain and China, by the early twentieth century it had become a dependable source of revenue for an otherwise faltering state. Between 1900 and 1906, when the suppression campaign began, duties on opium imports accounted for between 40-45% of customs revenues at Fujianese ports. The decision to prohibit the drug was, therefore, not an easy one. China’s problem with opium was partly an image problem. The Shanghai newspaper Shenbao proclaimed in 1906 ‘Since most of our countrymen wreck themselves by smoking opium, they represent our nation – a listless nation.’ Educated, mobile and nationalistic Chinese elites were only too aware that for many abroad, this image was China.

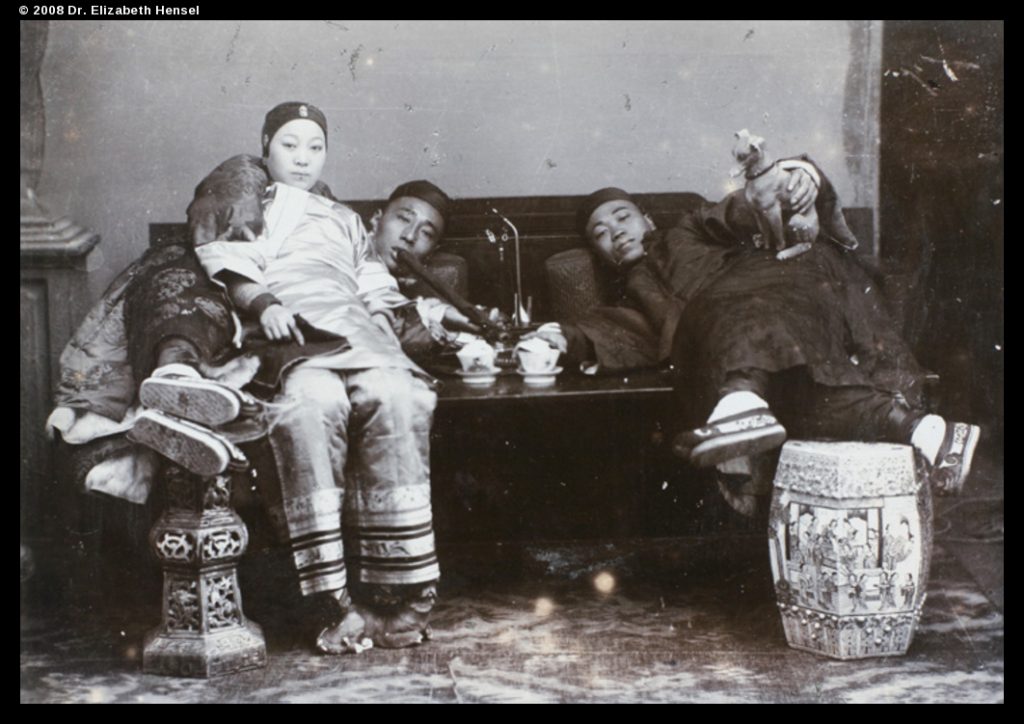

The image above, a posed photograph of an imagined typical scene in an opium den where men lay down to enjoy their pipes with prostitutes represented for many abroad why China was weak and could not be taken seriously internationally. Chinese nationalists internalised this message. The result was the prohibition campaign, launched despite the revenue derived from opium. The reality of opium smoking in China may, however, have been far more prosaic. The below image of scholars at their pipes contravenes many of the myths that circulated about opium addiction. The man in the front left is hardly a starved addict, while the scrolls on the back wall suggest that these men were part of an educated elite which took to the pipe as much as the poor. Recent scholarship has, in fact, suggested that the majority of opium smokers were harmless recreational users of the drug, particularly as smoking is a far less potent way to consume opiates than the pills or syringes now in use.

The Nanning opium burning marked a watershed. By 1920 central government authority had already splintered and within 10 years local warlords were deriving as much as 25% of their income from opium taxes. This income both attracted warlords to power and sustained their internecine conflict. Similarly, the prohibition of opium led to high prices and, this led to increasingly organised criminal networks with the power, and revenue, to corrupt governments. It is just possible that the effects of the cure were worse than the disease.