In the second of his two posts, Dr Andrew Hillier traces the history of the 1st Chinese Regiment, from its performance in the relief of Tianjin to its disbandment six years later.

Despite its record at Tianjin, to the dismay of both officers and men, the 1st Chinese Regiment was not actively engaged in the relief of Peking by the China Expeditionary Force that took place in August 1900. Instead, it was assigned to civilian tasks, mainly tending to the wounded and clearing the dead from the streets. Whilst this was partly because reinforcements had arrived from India, it was, its commanding officer, Major Barnes believed, mainly because westerners could not accept that any Chinese could be trusted to serve the allied cause.

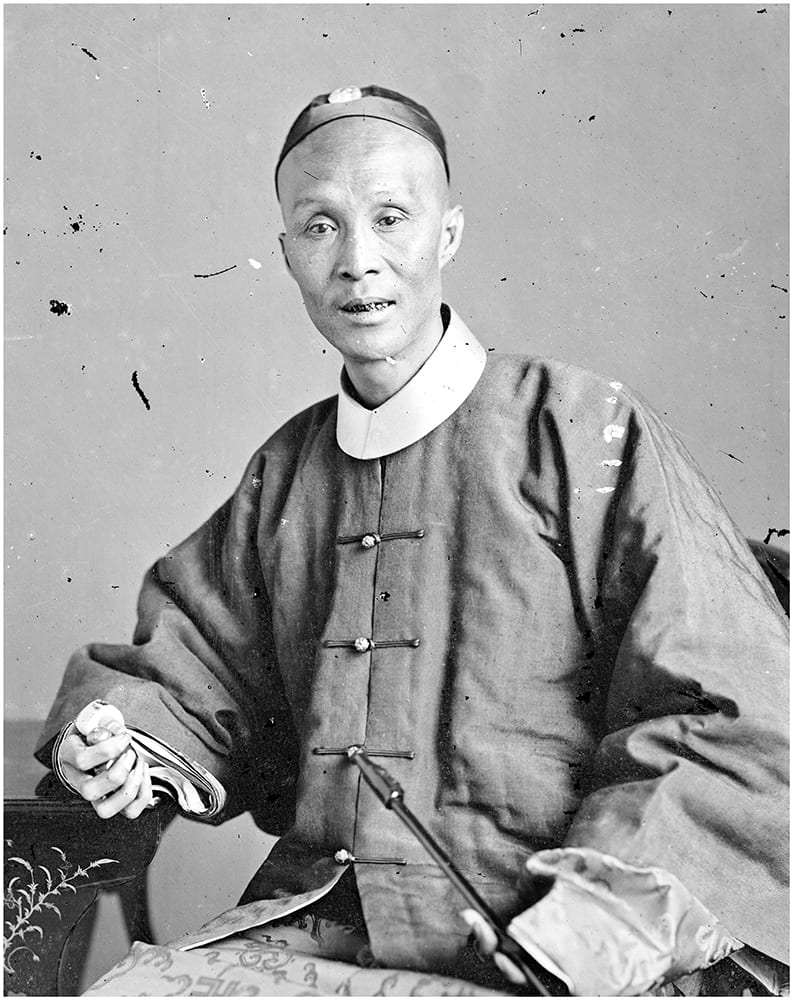

Rolling bandages for the wounded, Weihaiwei, 1900. Since some of the wounded were from the 1st Chinese Regiment, this was, albeit no doubt unintentionally, a moment of common cause between the two communities. Historical Photographs of China ref: Ca01-056.

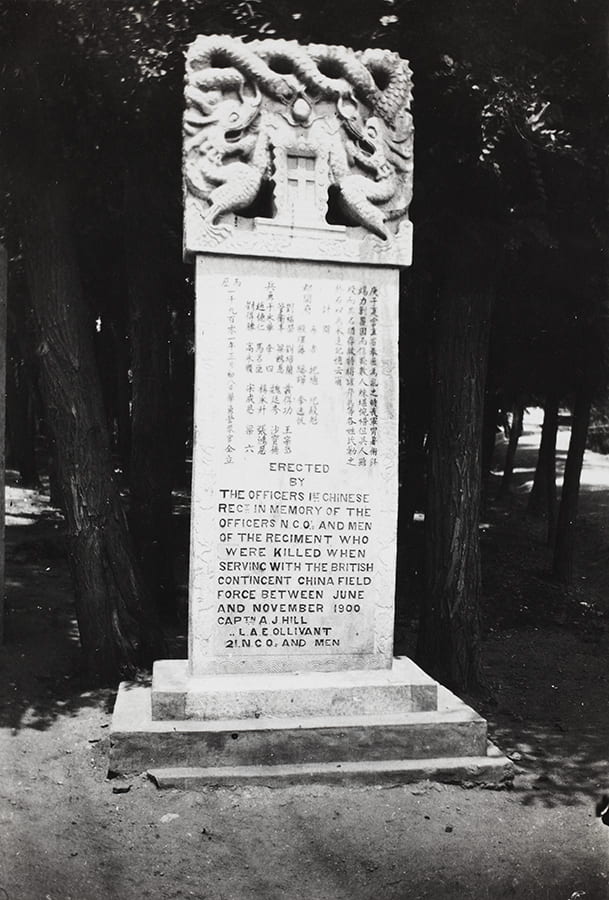

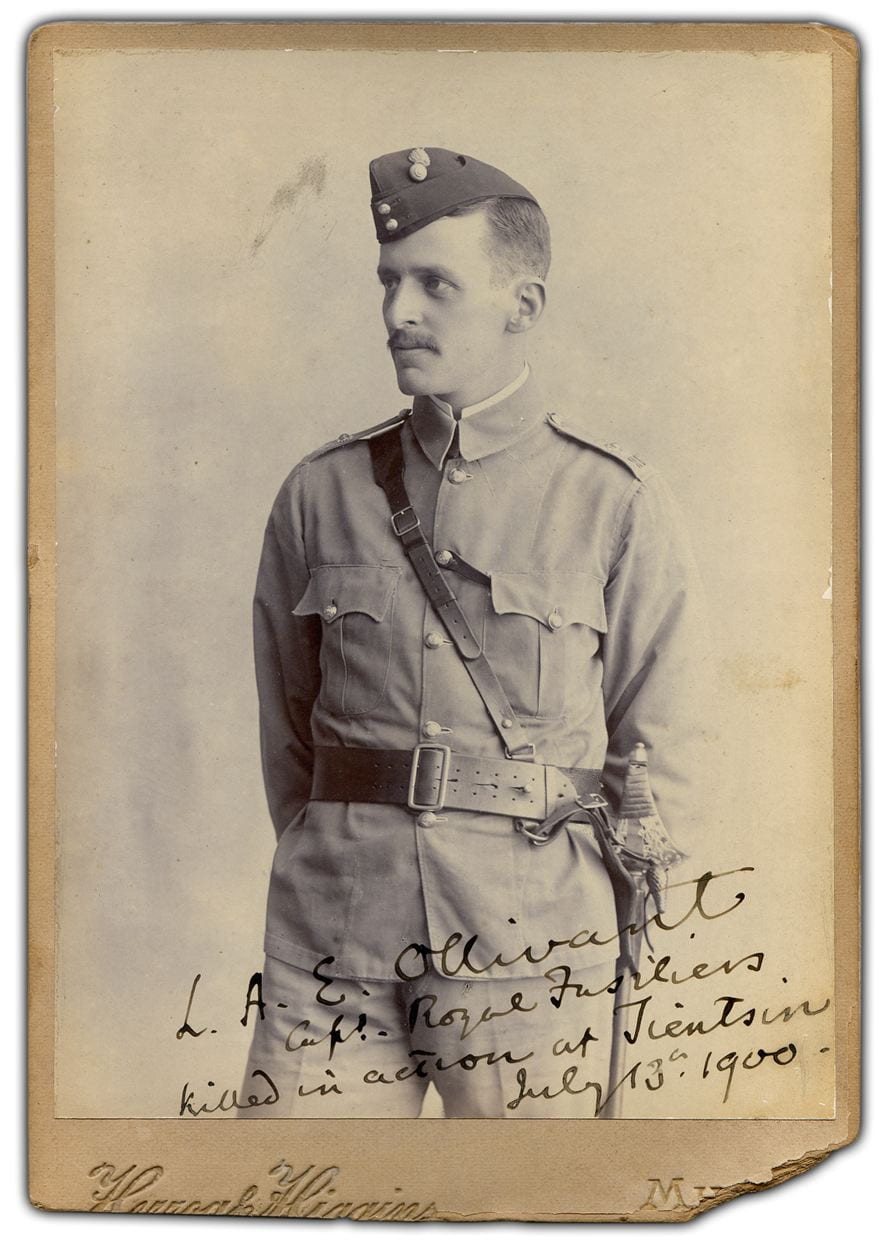

This ignominy was all the more bitter given the Regiment’s casualty rate. In total, it lost two officers and twenty-one men, although nine of these, including Captain Hill, died as a result of an accidental explosion, that occurred on 15 September 1900, when they were disposing of gunpowder seized from the Boxers.

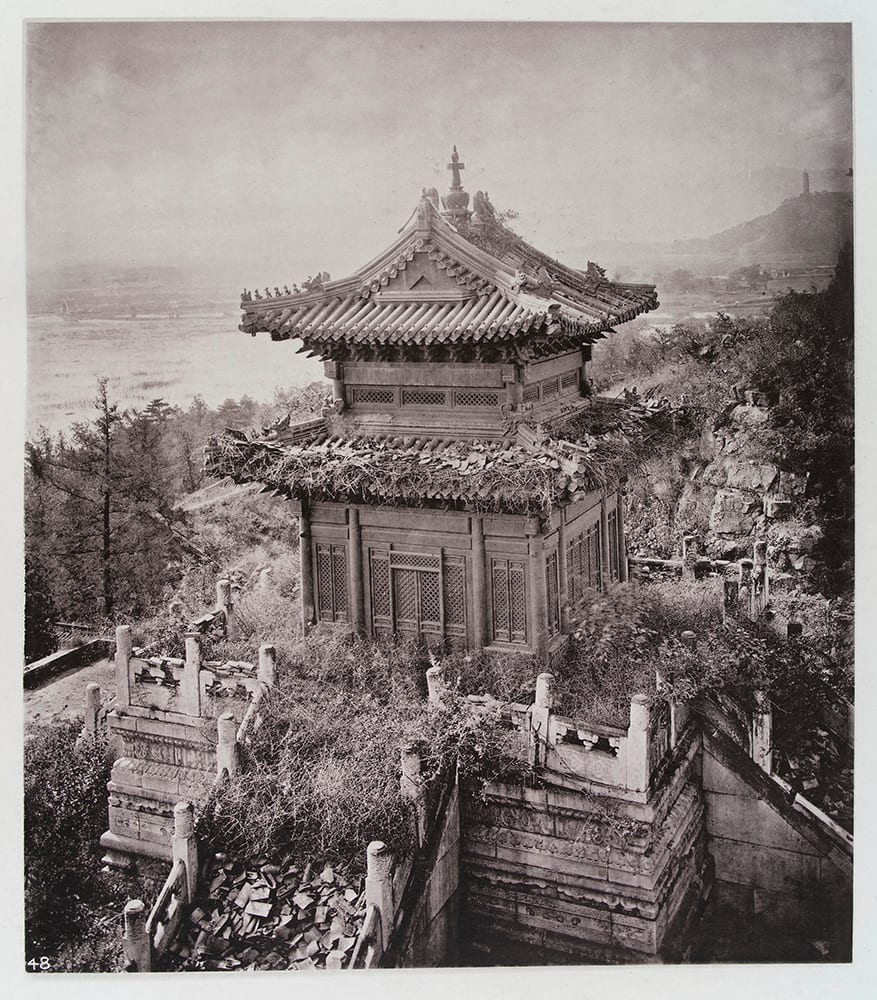

The regimental memorial on the road leading to the regimental barracks at Matou, Weihaiwei, commemorating both British officers and Chinese rank and file. Historical Photographs of China ref: BL04-73.

Barnes names all twenty-one of the Chinese casualties in his account of the conflict and the circumstances in which each of them lost their lives, beginning with No. 593, Private Yu yung-hua, who ‘died of wounds received in action at Tientsin railway station, 4th July 1900’, an attention to detail which reflected the good relationships and respect that had built up in the Regiment.[1] Although there were interpreters on hand, a number of the officers had learnt to speak Chinese, including one NCO, Sergeant Purdon, who became particularly proficient. This goodwill translated into the peace-keeping work that the Regiment carried out along the Peiho river in the aftermath of the Uprising.

However, there continued to be an ambiguous relationship between the rank and file and the local Chinese people. Reluctantly or not, ten Chinese members of the regiment took part in the triumphal procession that marched through the Forbidden City on 28 August 1900. Recorded in photographs distributed across the world, they were complicit in a display designed to inflict maximum humiliation on the Chinese. [2] And, although, according to Barnes, the Regiment had taken no part in the mass looting of Tianjin, Peking was a different story and ‘the unavoidable necessity being recognised, organised parties were, for a time, sent out to collect stuff from unoccupied houses, which was sold at auctions under the supervision of a prize committee’.[3] This provided a handsome dividend and many of the Chinese were able to leave the Regiment on the strength of the proceeds shortly afterwards.

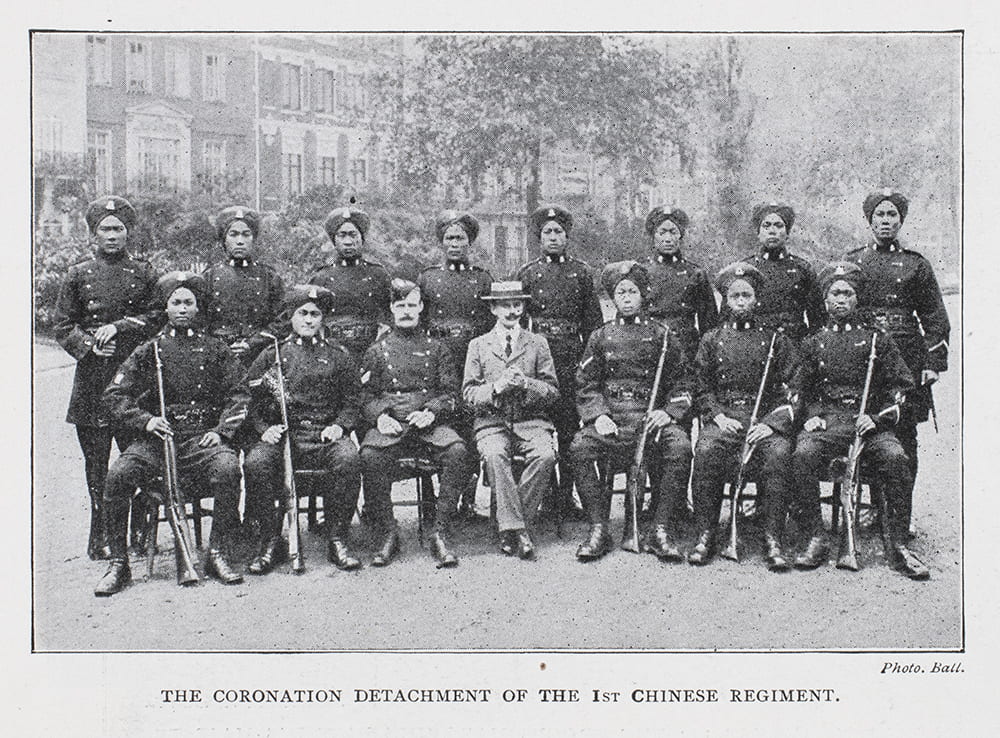

Members of the 1st Chinese Regiment attending the Coronation of King Edward VII, Illustrated London News, 16 August 1902, p.10.

However, it continued to attract recruits. By September 1901, numbering over 1300 men, it had become emblematic of the British presence in Weihai, sending a deputation to Edward VII’s coronation and frequently required to parade on ceremonial occasions attended by the Civil Commissioner, Sir James Stewart Lockhart (1902-1920).

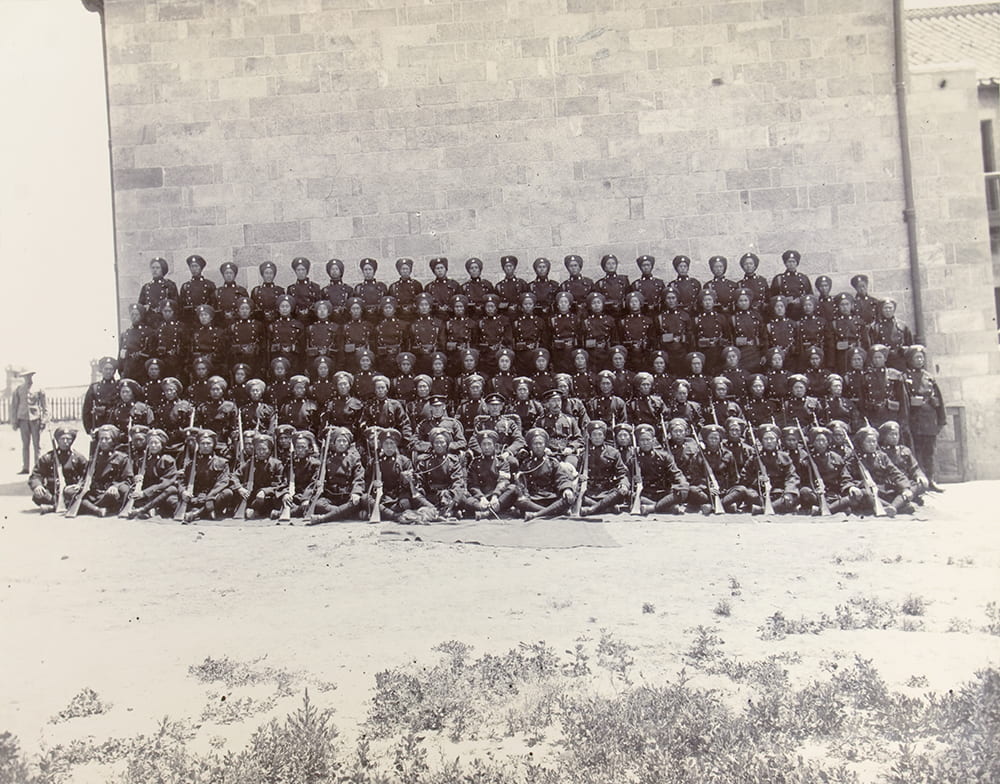

Review of 1st Chinese Regiment on Coronation Day, Weihaiwei, 9 August 1902. This photograph formed part of the Settlement’s annual report to the Colonial Office for 1903 (CO 1069/431. CHINA 11. Weihaiwei). Image © The National Archives, London, England. Historical Photographs of China ref: NA08-092.

Company of 1st British Chinese Regiment. The photograph formed part of the Settlement’s annual report to the Colonial Office for 1903, CO 1069/431. CHINA 11. Image © The National Archives, London, England. Historical Photographs of China ref: NA08-104.

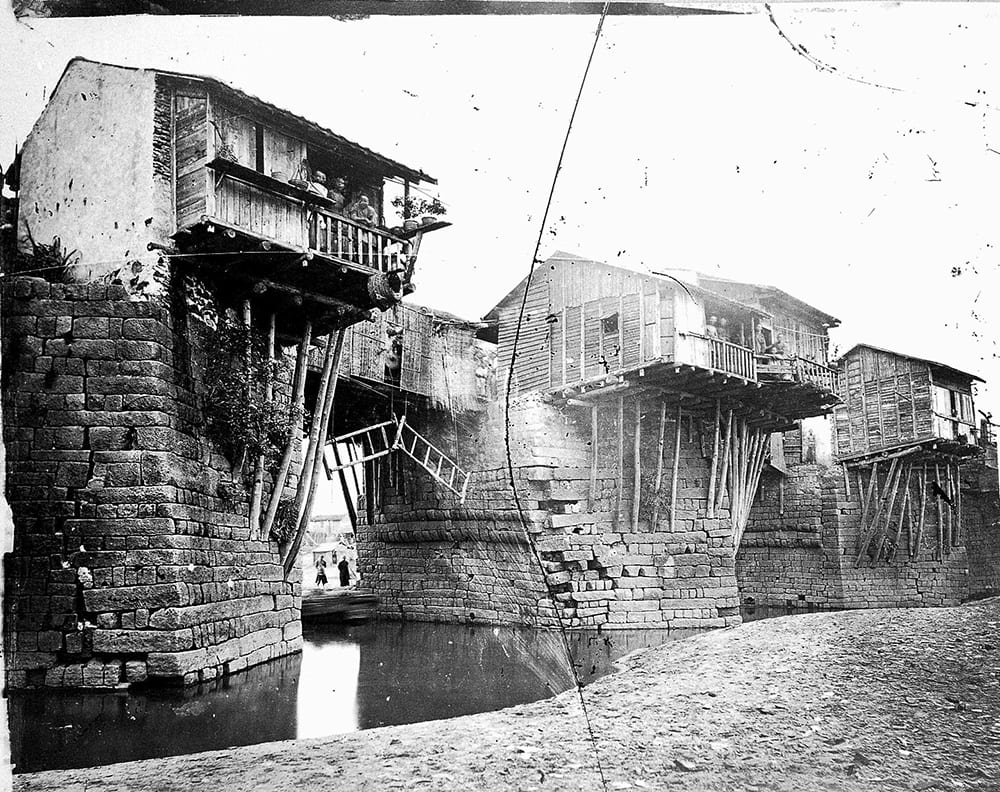

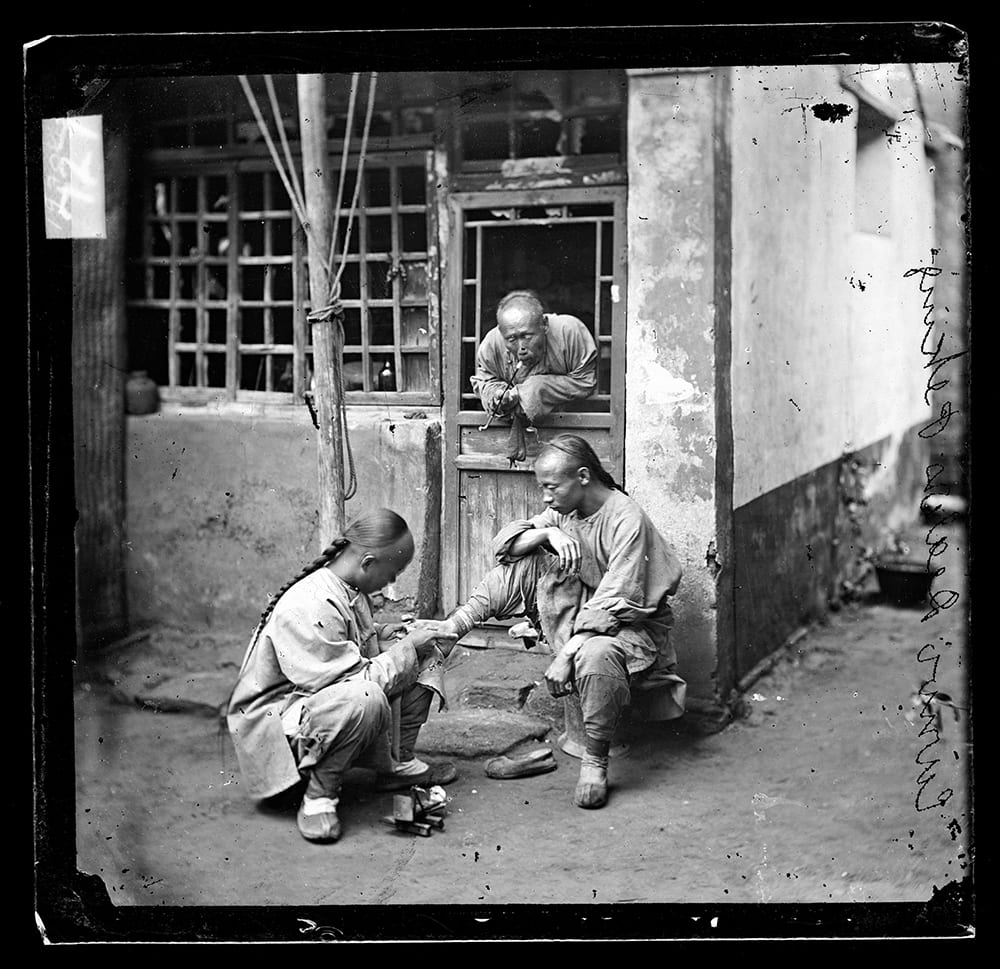

With Chinese photographers also setting up in business in the Settlement, a wealth of images of the regiment and its interaction with the local people were sent home to England and became part of family and military memory. [4]

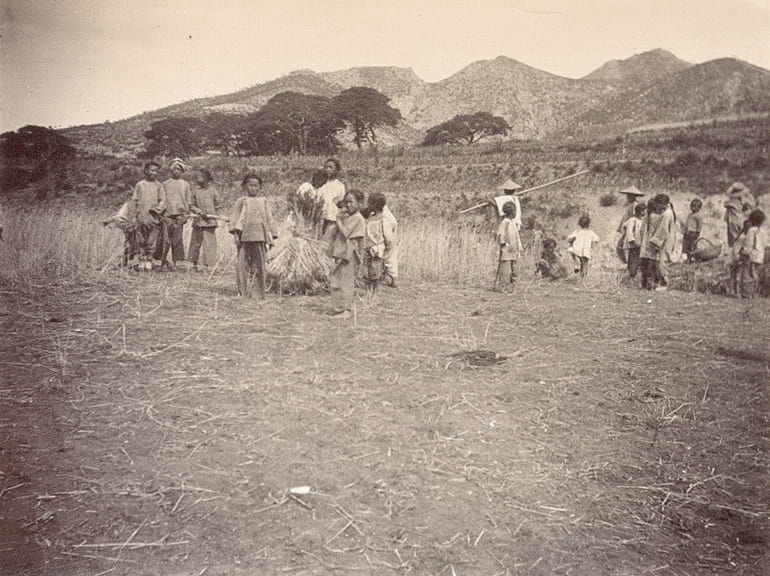

‘Harvesting’, from an album of fifty-two photographs taken and compiled by Captain C. D. Bruce (West Riding Regiment). According to the caption, the photograph was taken just outside Bruce’s house, Weihaiwei. NAM 1983-05-42-30. Image © National Army Museum.

‘Instruction of Recruits’, 1st Chinese Regiment, Weihaiwei. An example of an image that might have been sent home. Historical Photographs of China ref: Ru01-013.

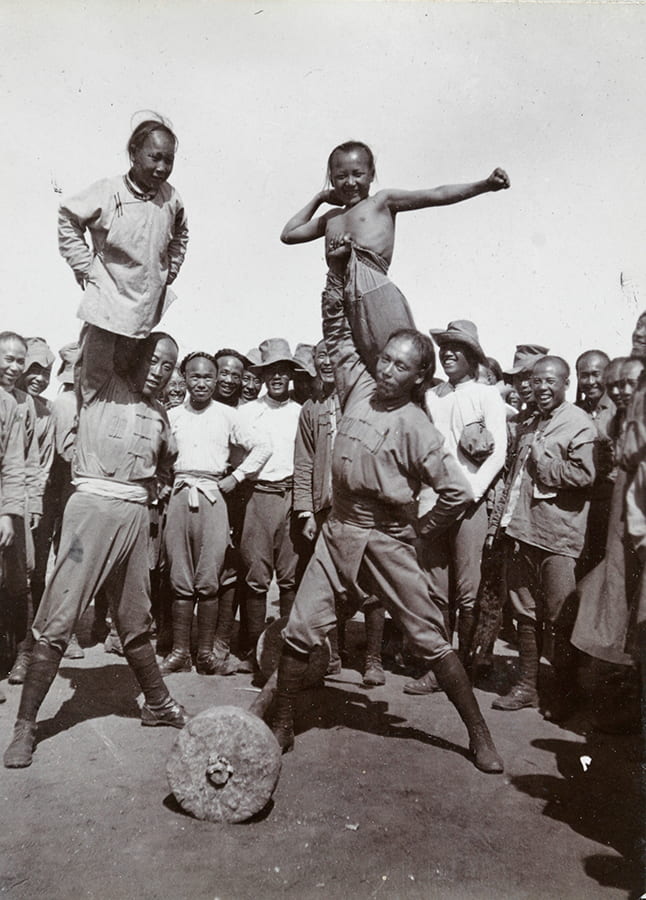

‘Feats of Strength by Soldiers’, 1st Chinese Regiment, Weihaiwei. Another example of an image that might have been sent home. Historical Photographs of China ref: Ru01-017.

This was encouraged by Lockhart, himself, who took a keen interest in photography. Establishing a good rapport with local officials, he believed that sending photographs home to England would evoke ‘a better understanding and sympathy for China’.[5]

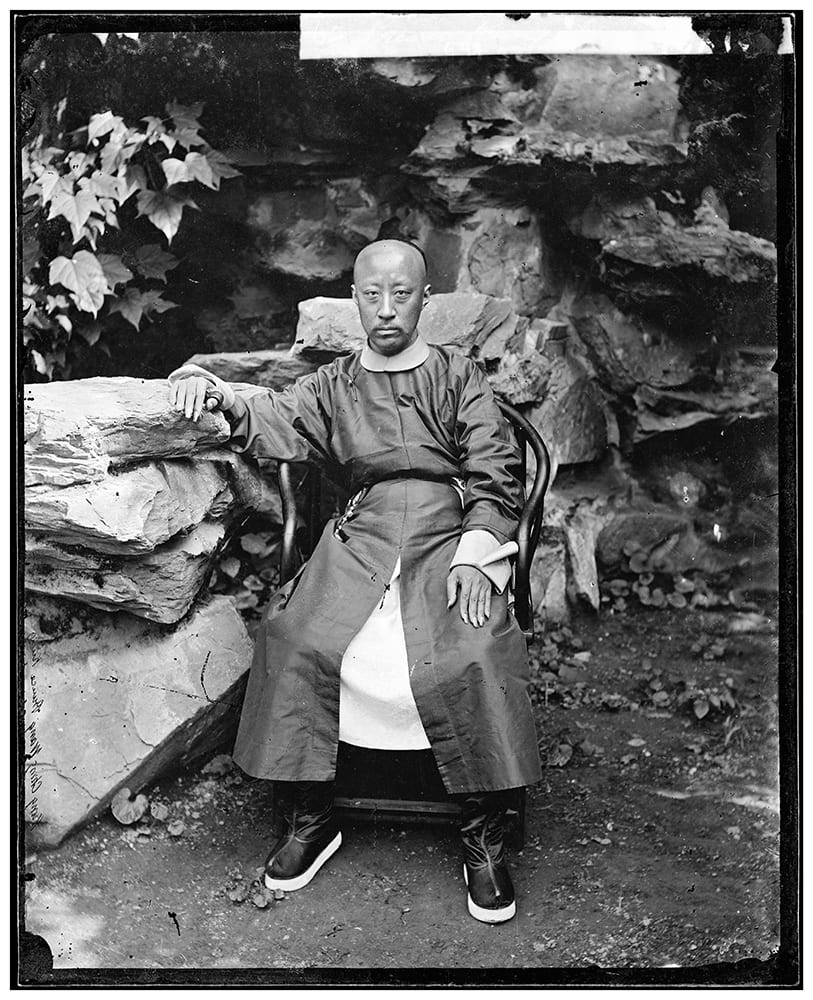

Left to right: Captain Barnes, Sir James Lockhart, and the Governor of Shandong, Tsi Nan Fu. From an album, CO 1069/432, CHINA 12. Shantung and Kiaochou: photographs of a tour in 1903. Image © The National Archives, London, England. Historical Photographs of China ref: NA07-047. See also NA07-050.

It was becoming clear, however, that there was little justification for the naval base at Weihai, let alone for maintaining a regiment there, given the expense involved. Over the next few years, its numbers were run down, some leaving to join the Chinese army, some to join the Shanghai Municipal Police and some to return to their farms. It was finally disbanded by Order in 1906.

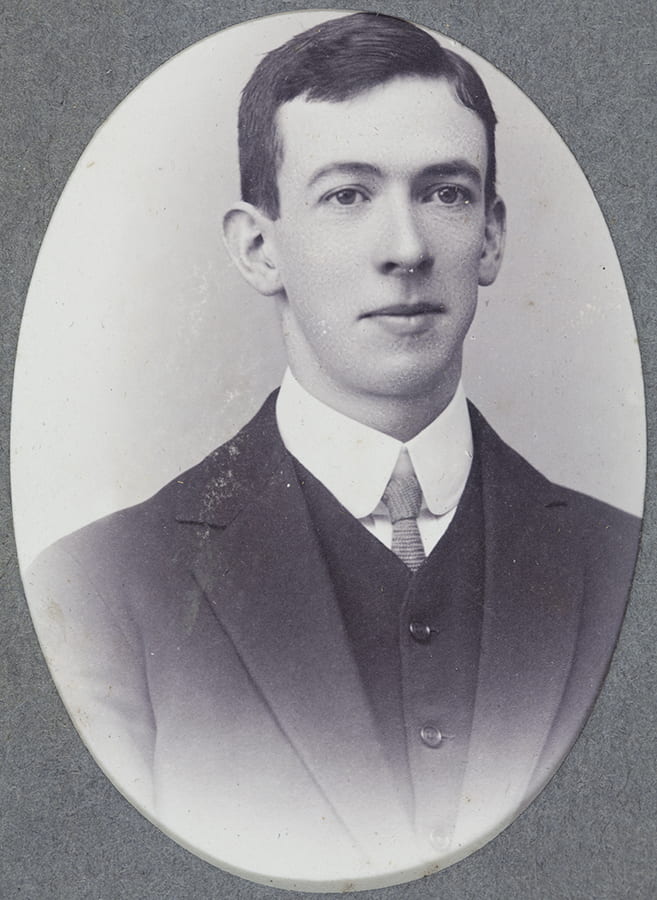

Most of the British officers returned to their home regiments, many later serving in the First World War. However, a number had developed a considerable interest in China, its language and culture and some of these stayed on: Colonel R.M. C. Ruxton, who had been seconded from the Essex Regiment in November 1901, went on to serve in China’s administration, Captain Barnes was appointed Commandant of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps and Major Bruce became Chief of the Shanghai Municipal Police. Perhaps, the most well-known of these was Captain G.E. Pereira, who, save for the war-time period, would spend the rest of his life in China, initially as Britain’s Military Attaché and later as an intrepid traveller. We will come to his adventurous life in the next post.

First World War memorial, Weihaiwei. The inscription on the front reads: “TO THE MEMORY OF ALL THOSE WHO FORMERLY RESIDED IN THIS TERRITORY WHETHER STATIONED OR AT SCHOOL OR OTHERWISE WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918”. Historical Photographs of China ref: BL04-71.

The members of the 1st Chinese Regiment who gave their lives in the First World War are named on the side of the war memorial in Weihaiwei (see BL04-71 above). Historical Photographs of China ref: Ru-s087.

[1] Arthur Alison Stuart Barnes, On active service with the Chinese Regiment: a record of the operations of the first Chinese Regiment in North China from March to October 1900 (London: Grant Richards, 1902), pp.146-149 ; for details of medals and awards, see A.J. Harfield, British and Indian Armies on the China Coast 1840 – 1985 (London: A & J Partnership, 1990), pp. 255-259.

[2] See James Hevia, English Lessons, pp.204-205. The Chinese are named by Barnes, On Active Service, pp. 146-149.

[3] Barnes, On Active Service, p.139.

[4] For photographs of Brooke, see NAM, 1983-05-42; for Bruce, see NAM, 1983-05-42; for Ruxton, see https://www.hpcbristol.net/collections/ruxton-family.

[5] Lockhart’s photographic collection can now be seen in the National Gallery of Scotland (George Watson’s College); see also Sara Stevenson, ‘The Empire Looks Back, Subverting the Imperial Gaze’, History of Photography, 35 (2011) pp. 142-156 and Shiona Airlie, The Thistle and Bamboo: the life and times of Sir James Stewart Lockhart (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1989).

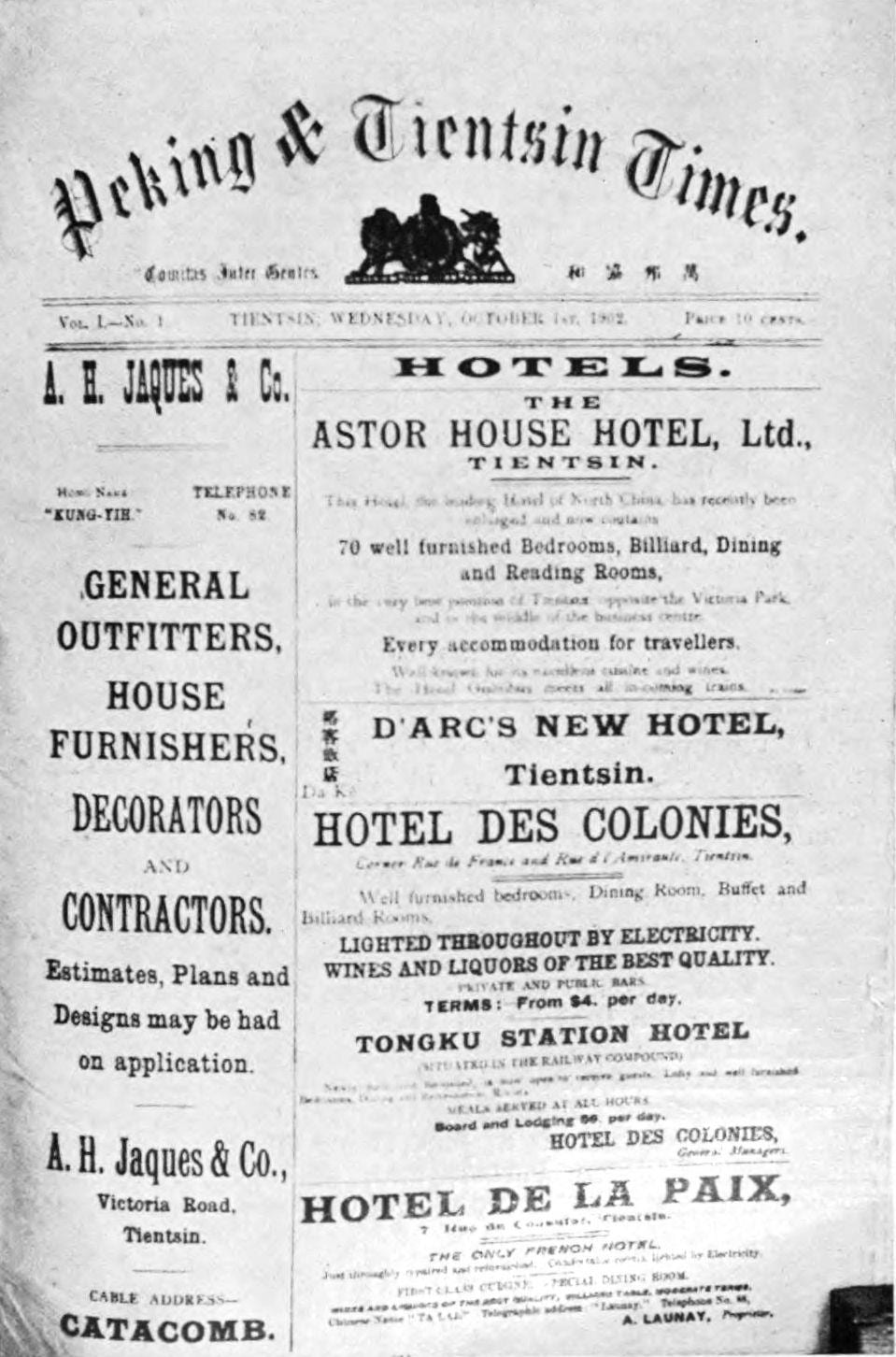

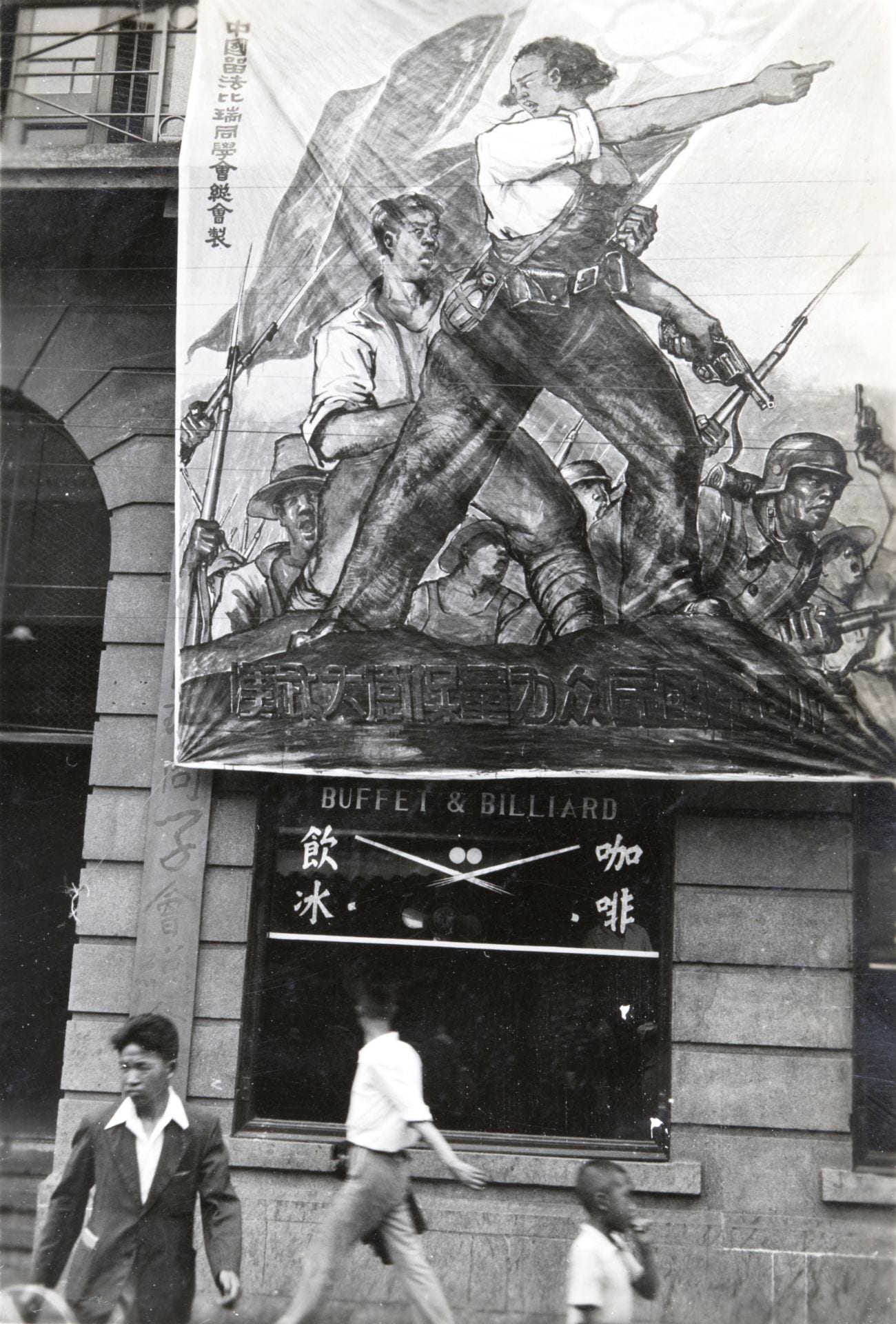

Woodhead appeared all-powerful in Tianjin between the world wars, though he did have some competition. The North China Commerce newspaper was established in 1920 as an English-run weekly but didn’t last long while the American-owned North China Star was also published in Tianjin. This was real competition – the American State Department estimated the paper’s daily circulation in 1921 as 2,500, more than double Woodhead’s Peking and Tientsin Times, but also noted that the Star was far less influential than Woodhead’s paper which to men like Woodhead was what really counted.

Woodhead appeared all-powerful in Tianjin between the world wars, though he did have some competition. The North China Commerce newspaper was established in 1920 as an English-run weekly but didn’t last long while the American-owned North China Star was also published in Tianjin. This was real competition – the American State Department estimated the paper’s daily circulation in 1921 as 2,500, more than double Woodhead’s Peking and Tientsin Times, but also noted that the Star was far less influential than Woodhead’s paper which to men like Woodhead was what really counted.

![Scots Guards & Shanghai Scottish Pipers, HPC ref AL-s04. The Scots Guards arrived in Shanghai on 2 July 1928 and were based there until 20 January 1929 as part of the British Shanghai Defence Force which was established in January 1927 following an attack on the British concession in Hankow (Hankou) and the surrender of the concession.[2] Note the Chinese on-lookers for whom this was not only a routine ceremonial but, in the highly-charged circumstances of the time, a powerful demonstration of British military capacity.](https://hpchina.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2018/11/AL-s04-25q9825.jpg)