Our Guest blogger this week is Simon Drakeford, whose book about rugby in Shanghai titled It’s a Rough Game But Good Sport has just been published. More details can be found at www.treatyportsport.com

Given the importance and prevalence of the numerous sports played in the treaty port of Shanghai, there are surprisingly few photographs of sportsmen in the public photographic archive.

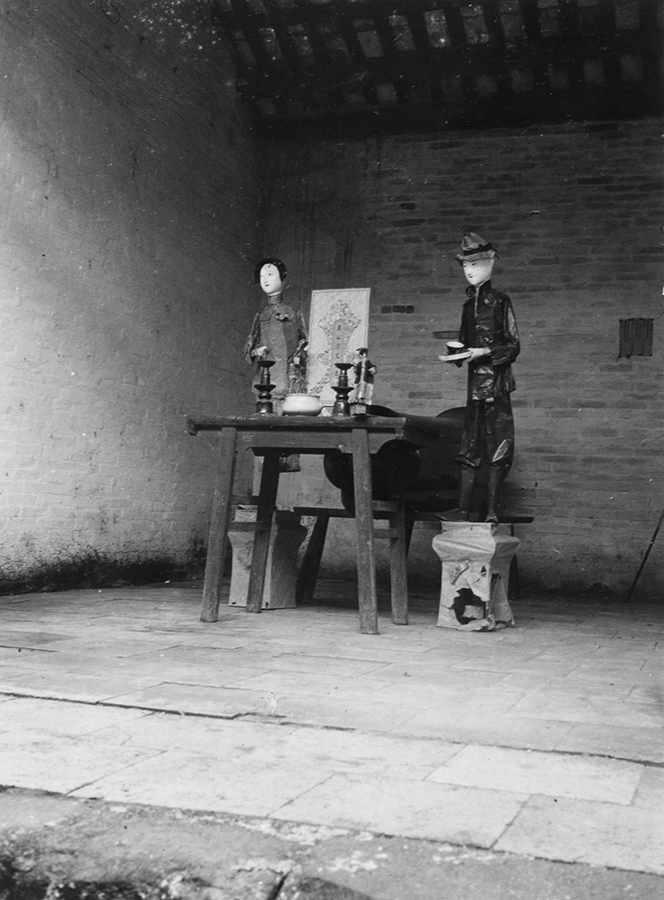

Born in 1905 in Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales, policeman Percy Poole, looking very formal in this photo, was one of the most, if not the most prolific rugby playing policeman in Shanghai in the 1930s. After leaving the Shanghai Municipal Police in 1937, he became an Usher in Shanghai’s British Supreme Court.

He is first seen in the rugby records in November 1930. Before his last game on New Year’s Eve 1938, he played in at least 80 games of rugby in Shanghai. His primary team was the Shanghai Municipal Police but he also featured in many Shanghai first XV fixtures. This included numerous matches against the U.S. Fourth Marines first XV, several against British United Services XVs, visiting Japanese teams from Meiji University and the Imperial Japanese Railways and two matches in the most important fixture of the 1930s, representing Shanghai against Hong Kong in 1934 and 1935.

Percy Poole was also a boxer of some repute. Before arriving in Shanghai he boxed for the Royal Horse Guards in London from 1924 to 1929. Amongst other famous boxers of this era, he sparred with Italian boxer Primo Carnera, nicknamed the Ambling Alp (he was 197cm tall), who became the heavyweight champion of the World in 1933.

A Percy John Poole appears on a Royal Navy list as being a volunteer in the Hong Kong Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in October 1940. Intriguingly I cannot find his name either on the casualty lists or the internment camp lists which suggest he was able to leave Hong Kong before the Japanese arrived in December 1941. Where did he go and is he the same rugby playing Shanghai Policeman? He is next traced arriving back in the UK in December accompanied by his wife, Mei Yuen and daughter.

Editor’s note: rugby football has had a renaissance in Shanghai, led by the re-establishment in 1997 of the Shanghai Ruby Football Club.

本期作客博主是Simon Drakeford,他关于上海橄榄球历史的的最新著作即将出版。关于本书的更多内容请移步:www.treatyportsport.com

上海作为五个通商口岸之一,有许多受欢迎的重点体育项目,但是公共图片档案资料中的运动员照片却寥寥无几。

这位在照片中衣冠楚楚的珀西·普尔(Percy Poole),1905年出生于威尔士蒙茅斯郡纽波特,是20世纪30年代上海橄榄球界进球数最多的警察之一。 1937年,他从上海公共租界巡捕房离职后,成为英国在华最高法院的一名引座员。

关于他的橄榄球记录始见于1930年11月,直到1938年除夕他的最后一场球赛不下80场的上海橄榄球赛事上有迹可循。他主要效力于上海公共租界巡捕房队, 但同时也活跃在许多上海队伍的首发十五人阵营中, 包括对阵美国海军四师的多场比赛、英国联合服务队的几场、来自日本明治大学和日本帝国铁路的访问队的几场对决,以及在1934和1935年的两场20世纪30年代最重要的橄榄球比赛中,代表上海对抗香港。

珀西·普尔同时也是一名小有名气的拳击手。还没来上海前的1924年至1929年间,他就为伦敦皇家骑卫队的拳击队效力。在同一时代的著名拳击手中,他曾和来自意大利的卡尼拉1940年10月的香港皇家海军志愿者名单上曾经出现“珀西·约翰·普尔”这个名字。但令人费解的是,遇难者名单或拘留营的名单上都找不到他的名字,也无法推断他是否在1941年12月日军侵华前成功离开香港。这个人去了哪儿?他是否就是那个在上海打橄榄球的警察?最后能追寻到的他的踪迹是他于12月和他的夫人袁梅(音:Mei Yuen)及其女儿回到英国。

编者寄语:1997年上海橄榄球俱乐部重建在上海引起了新热潮