Katya Knyazeva, from Novosibirsk, Russia, is a historian and a journalist whose work focuses on urban form, heritage preservation and the Russian diaspora in Shanghai. She is the author of the two-volume history and photographic atlas Shanghai Old Town – Topography of a Phantom City (Suzhou Creek Press, 2015 and 2018). Katya’s articles on history and architecture appear in international media and in her blog http://avezink.livejournal.com. She is currently a research fellow at the University of Eastern Piedmont, Italy.

The birth of Shanghai is usually pinned to the year 1291, when a market town located near the confluence of two waterways, Huangpu and Wusong, was promoted to the status of a county, subordinate to the prefecture city of Songjiang. For the next 250 years Shanghai grew in size and population, but remained shapeless, until an invasion of coastal pirates, in spring 1553, prompted the construction of the defence wall around the city. The pirates, locally referred to as the ‘Japanese,’ were contraband traders and adventurers of various racial origins, who sailed the coast of China in defiance of Ming proscription, attacking rich settlements like Shanghai.[i]

According to the local gazetteers, it only took three months to build the wall and dig the defence moat next to it. The wall was between eight and ten meters high, made of tamped earth, flat on the top, and faced with black bricks on the outer side. There were 3,600 embrasures on the top edge, interspersed with several lookout platforms facing the bend of the Huangpu River, to allow early sighting of pirate ships. The moat was six meters deep and up to twenty meters wide in some places; it connected to the Huangpu River and the city waterways, and the drawbridges across it could be lifted at any moment.

After these fortifications were built, no force could take Shanghai by surprise. Any invader would have to raft across the moat or cross a drawbridge near one of the six city gates in full view of the armed soldiers stationed there. At eight in the evening, guards locked the city gates with huge wooden bolts. City dwellers who lingered in the riverside markets and failed to get back before curfew had to bribe the guards to crack open the gates or wait outside until sunrise, in the grim company of bamboo cages containing the decapitated heads of executed criminals, hanging from the embrasures.

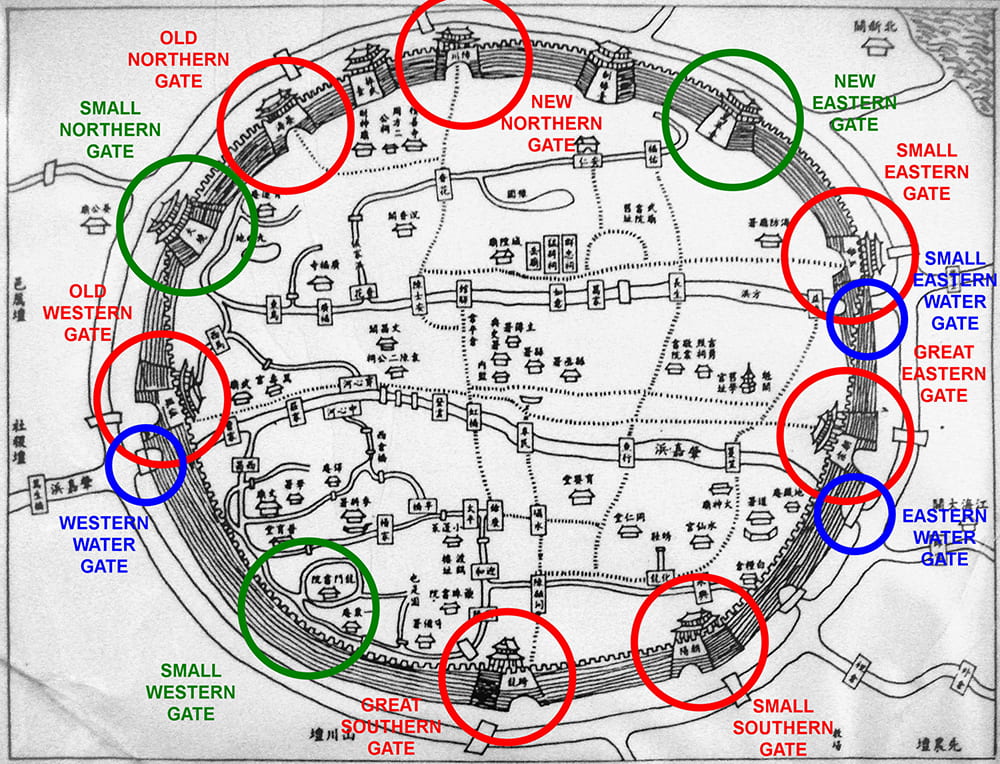

Plan of Shanghai, c.1860, showing old gates in red, new gates in green, and water gates in blue. The Huangpu River is at the top right. Source: Wikipedia.

One of Shanghai nobles, Fan Lian, who partially sponsored the construction of the city wall, described its efficacy in 1556, when ‘Japanese’ pirates tried to rob Shanghai again:

During the day and into the night, the pirates hid at the foot of the wall. Then they put up ladders to come over. Fortunately, a brave, Yang Tian, shouted. One pirate, who had already climbed the wall, killed Yang Tian. Some of the local troops vigorously attacked, stabbing the invaders and sending them falling to the ground. The crowd picked up bricks and pushed stones over to drop on them and crush them. Then the tide came in and the pirates fled. Sixty-seven were drowned in the moat of the wall. As a result, the siege was broken. To this day sacrifices are offered in Shanghai to Yang Tian.[ii]

Initially, the city wall had six gates – four big and two small – to allow the passage of pedestrians and boats in and out of the city. In 1860, an extra north-facing gate was constructed to ease the access to the foreign settlements growing to the north of the Chinese City. In 1906, inner city creeks began to be filled and three new gates were cut through the wall, but they only lasted a few years, because in 1912 the wall started to be torn down, and the moat was filled and paved.

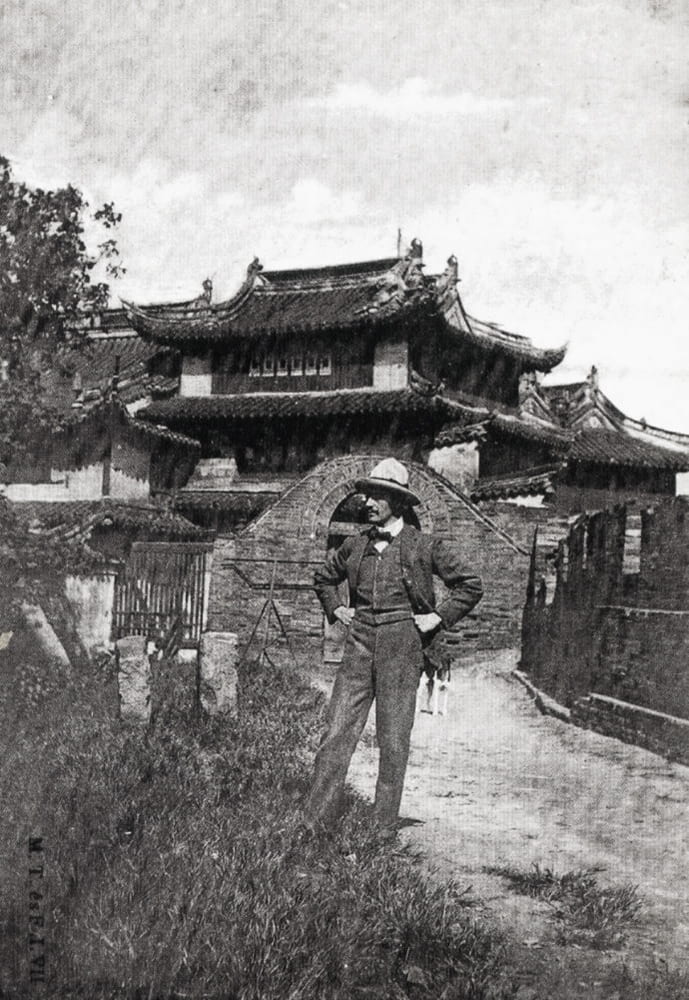

Foreigner on the city wall next to Phoenix Tower, Shanghai. Source unknown.

While the city wall was still standing, many western travellers found it a fascinating structure, and the photographs in the collection of Historical Photographs of China are a great way to explore it. Taking a suggestion from Rev. C. E. Darwent, who proposed a walking route on top of the city wall in his Shanghai: a handbook for travellers and residents to the chief objects of interest in and around the foreign settlement and native city (1904), we begin at the Old North Gate and go clockwise around the city. The whole route, about 4 km long, would take about one hour – or ‘two hours and a half, if the temples en route are to be visited.’[iii]

The photograph below shows the Old North Gate (formally, Yanhaimen 宴海门) when it was Shanghai’s only north-facing gate. Built in 1553, it opened to a marshy and unpopulated country, dotted with graves. One of the few people brave enough to try living here was the young intellectual Wang Tao, who moved to Shanghai in 1848 and spent a few months in a cottage north of the city wall, where the endless ‘stretch of desolate grave mounds’ came close to his doorstep and ‘a dense clump of trees added to the eeriness of the place.’[iv] The photograph from 1858, below, shows this somber landscape; the decrepit pavilion perched on the city wall is one of the lookout towers, known as Zhenwutai (振武台):

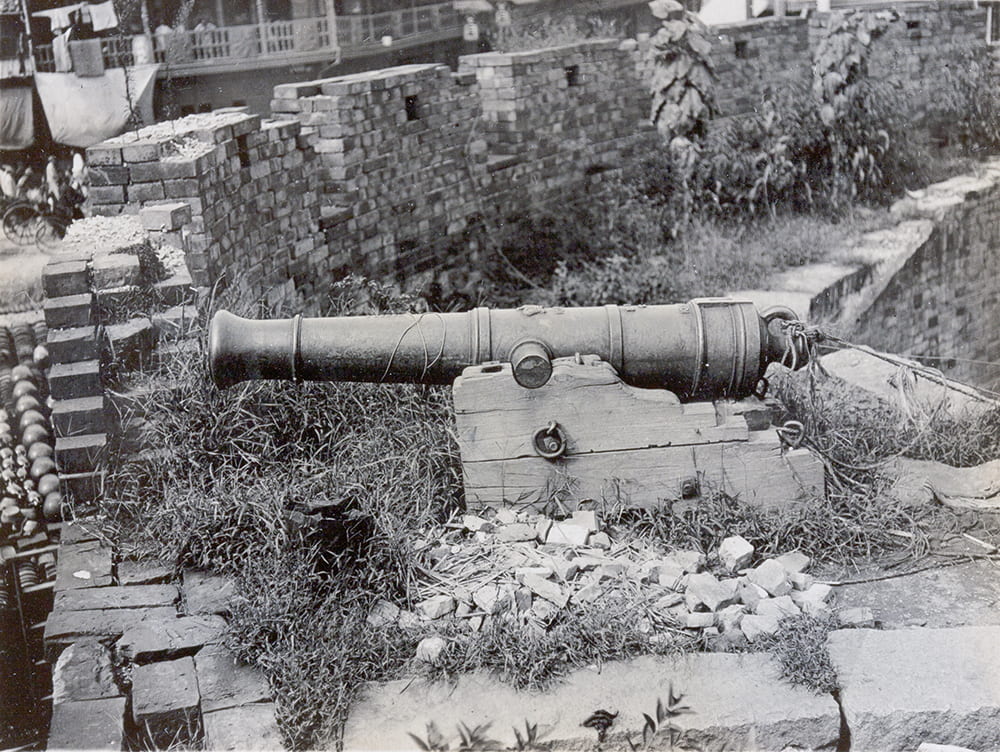

By the turn of the twentieth century, the French Concession to the north of the walled city was growing fast and a number of its streets ended at the edge of the moat, which acted as the boundary between the two territories. Continuing to walk on top of the wall in the clockwise direction and passing the Zhenwutai fortress, one would stumble on an old British cannon – a reminder of the 1850s, when the city was preparing to reflect an attack by the Taipings.

The next gate on the itinerary is the New North Gate – formally called Zhangchuanmen (障川门) – which was added in 1860. Several years earlier, the French artillery had damaged the wall while trying to oust the Small Swords rebels, who had barricaded themselves inside the city. The New North Gate – or Porte Montauban – was the main portal between the Chinese City and the French Concession, always in heavy use. Darwent pointed out that

the entrances to the [gates] are very interesting – always crowded, always dirty, always littered up with lepers and with beggars advertising their self-made sores, always sloppy with the water spilt by the water-carriers, a wild jostle of coolies, silk-arrayed gentlemen, sedan-chairs, hobbling women, melancholy dogs, and all the flotsam and jetsam of a Chinese crowd. The photographer and seeker after the picturesque errs greatly if he misses these city gates.

Looking from the top of the New North Gate toward the French Concession, one saw crowded streets and endless rows of shops. Rickshaw drivers waited at the end of the bridge across the moat, ready to take passengers into the settlements. Manoeuvrable as they were, these vehicles could not navigate the narrow streets and stepped bridges of the Chinese City. By the late nineteenth century, even the most old-fashioned of residents usually needed to pass through the city gates at least twice a day, so the gate-closing curfew time was changed, to start at a later time of ten o’clock in the evening.

Shops, rickshaws and wheelbarrows outside the New North Gate, Shanghai, c.1890-1900. HPC ref: Wr-s019.

Continuing eastward on the wall, one approached a large pavilion – the Phoenix Tower (Danfenglou 丹凤楼) – built in 1584 on the initiative of the Imperial Censor Qin Jiaji who converted one of the lookout towers into a three-story temple dedicated to the goddess Tianhou and various Taoist gods. When the temple was consecrated, Qin bestowed an antique plaque spelling “Phoenix Tower” salvaged from the Temple of the Smooth Passage (Shunjimiao 顺济庙), which had occupied the same spot two centuries earlier. The plaque was hung over the entrance to the new temple, and couplets by the poet Yang Weizhen were inscribed on vertical strips by the door: “Past twelve bamboo curtains and one hundred steps, the phoenix rises to heaven…”[v]

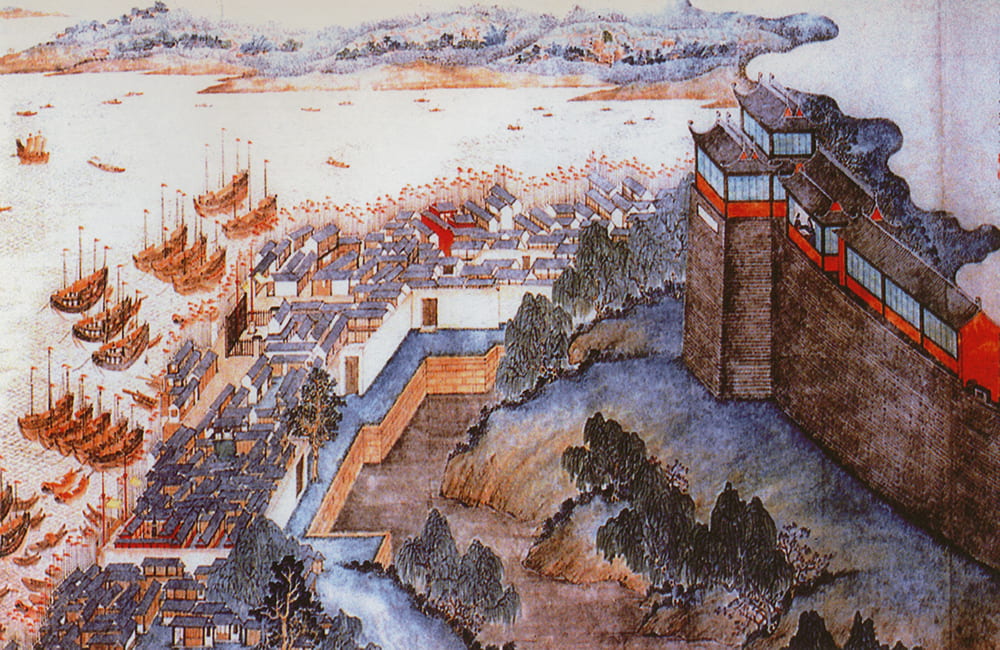

The Phoenix Tower was the tallest structure in Ming and Qing Shanghai, offering spectacular panoramic views of the city within the walls and the bustling neighbourhood between the city and the river. The painter Cao Shiting depicted the Phoenix Tower (below) sometime after 1820, and his painting became the best-known image of Shanghai before the concession era.

View of the Phoenix Tower (上海丹凤楼胜景图), Shanghai, by Cao Shiting (曹史亭). Source: Shanghai Library Archive.

The riverside suburb east of the city was set on fire and mostly destroyed in 1855, while joint Chinese and French forces were ousting out the Small Swords. Because of this accidental clearance, the photograph below shows an uninterrupted view north past the Phoenix Tower, all the way to the English Bund and the twin flagpoles of the Custom House.

Phoenix Tower on the east wall of Chinese City, looking towards the Bund, Shanghai, 1850s. Photograph by Robert Sillar. HPC ref: VH02-120.

On the northern wall, east of the New North Gate, looking east, toward the Huangpu River and French Concession, Shanghai, c.1902-1911. HPC ref: WG01-106

To the south of the Phoenix Tower, in 1909, the New East Gate, or Fuyoumen (福佑门), was carved through the city wall; it only had a few years of life. The next gate on the route – the Little East Gate, formally called Treasure Belt Gate (Baodaimen 宝带门) – was popular with travellers, who were attracted to the vibrancy of this neighbourhood. The Little East Gate was the primary passage between the walled city and the port – the source of Shanghai’s wealth and its reason to be.

Little East Gate, Shanghai, c.1910. Source: Shanghai Library Archive.

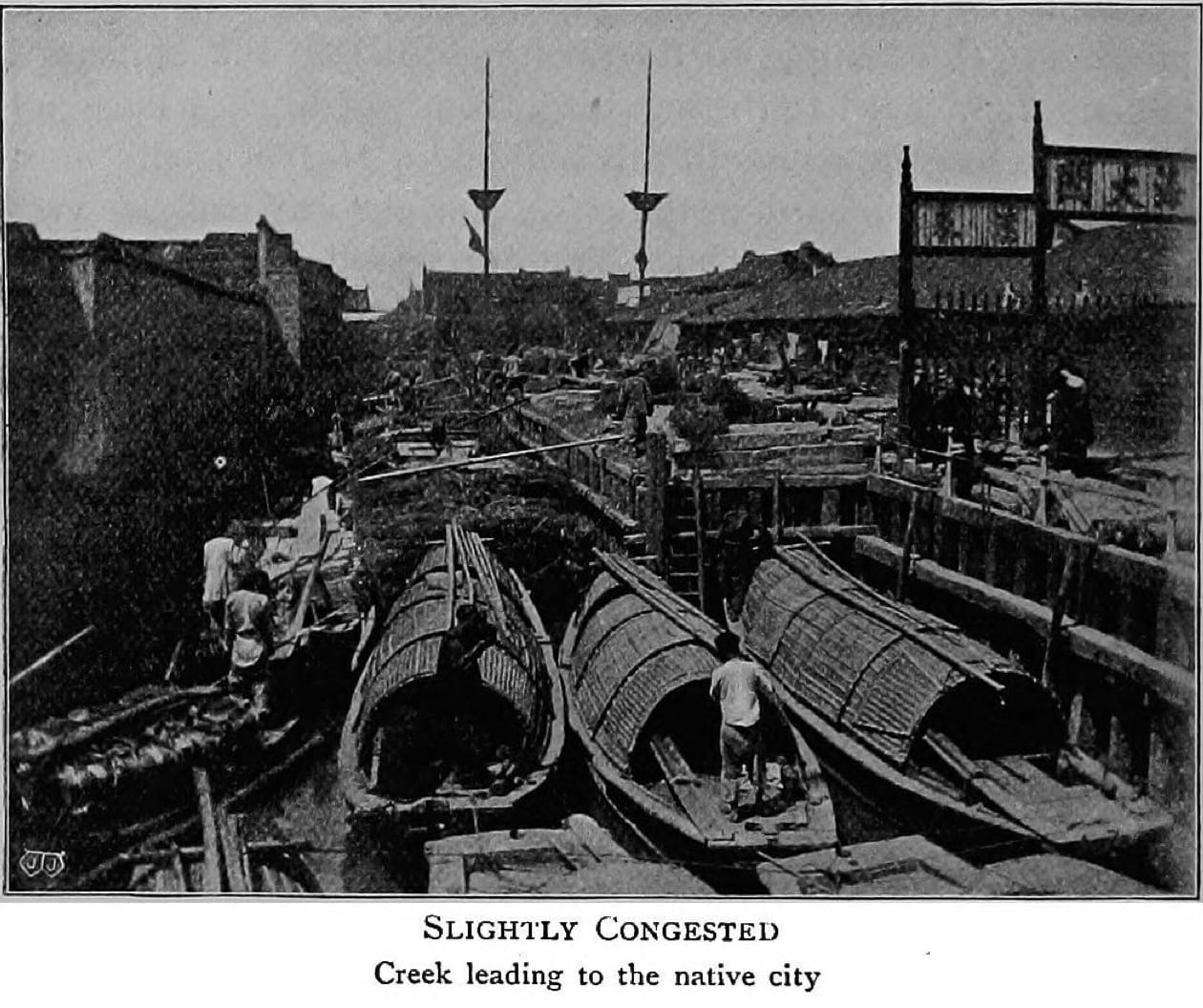

Travelling down the wall in the southern direction, one came next to the Big East Gate, or Chaozongmen (朝宗门). This had a water gate next to it, under which Zhaojia Creek passed into the city. The creek was always so crowded with stationary boats and barges that navigation was virtually impossible, and those travelling inland from the port avoided the walled city and its waterways. The illustration from Darwent’s Guide to Shanghai (below) portrays this congestion. A local gazetteer also observed that “in search of small profits, rich people build up the embankments and narrow the creeks. As a result, droughts make common folk cry from thirst, heavy rainfall overfills the gutters. Dirty water is one problem, fire hazard is another.”[vi]

Illustration from ‘Shanghai: a handbook for travellers and residents to the chief objects of interest in and around the foreign settlement and native city’ by C. E. Darwent (1904), p. 124.

The next gate on the route was the Little South Gate, made up of a big water gate and a small one for pedestrians; both connected the city with the bustling commercial suburb of Dongjiadu. These passages were well known to the American and French missionaries, who lived in this area and referred to it as Tunkadoo. After passing the ‘flourishing mission of the American Southern Presbyterians’ outside the city wall, one arrived at Shanghai’s southernmost gate – Big South Gate. It was the terminus of the only wide and straight avenue inside the walled city, which started at the magistrate’s yamen.

The county magistrate could assign punishments of great cruelty, but the death penalty required a special edict from the Imperial Board of Punishments and had to be carried out with byzantine official ceremony. On the day an execution was scheduled, a formal procession of officials from the office of the magistrate would parade on horseback and leave the walled city through the Big South Gate. The cavalcade would ride on a drawbridge across the defence moat, and the bridge would be immediately lifted behind them. By the testimony of W. MacFarlane, who attended an execution in the 1870s, ‘the mandarins and military officers […] generally number about twenty, all mounted on ponies, and they ride round in a circle making as much noise as they can by clattering of hoofs and tinkling of bells, until some small crackers are set off, at which signal the executioner cuts off the head of the prisoner with one fell swoop of his sword.’[vii]

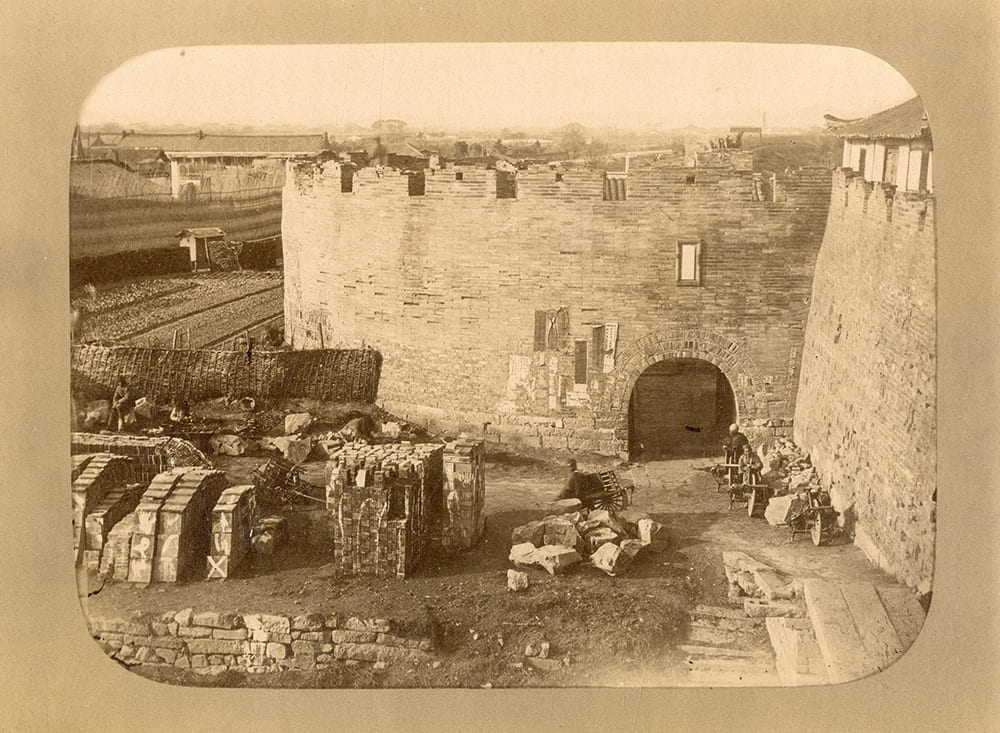

Having walked around the southern curve of the city, one started a northward journey along the western wall. After 1909, one would pass over the Little West Gate, or Culture-Oriented Gate (Shangwenmen 尚文门), named thus for its proximity to the Confucian Temple (Wenmiao 文庙). The photograph below was taken from the city wall for, or by, the British officers temporarily stationed in the temple in 1863 in preparation for the Taiping invasion; the Confucian Temple is in the middle distance.

Continuing to walk along the western edge of the city, one saw few residences and many gardens. Darwent (1904) explained: ‘Walled cities always had to have open spaces in them, to grow as much food as possible in times of siege.’ George Smith, who had himself carried along the wall in a sedan chair in the late 1840s, found that the west of the walled city ‘presented a rural aspect, forming one succession of pleasant gardens, with only a few houses interspersed,’ and that ‘outside the wall there was scarcely a house to be seen.’[viii] Half a century later, the intramural area was still undeveloped, but the French Concession all around the walled city was built up with terraced houses (lilong). The image below shows the gardens in the walled city and the densely built French Concession beyond the wall.

View from the Dajing Pavilion over the western part of the walled city, Shanghai, c.1900. Source: Shanghai Library Archive.

With most of the population living in the city’s east, a single west-facing gate was sufficient. Officially named Ceremonial Phoenix Gate (Yifengmen 仪凤门), it was built in 1553, and according to existing photographs, it was quite substantial. As Macfarlane (1881) described it: ‘We pass through the first archway, the outer gate, and then are within the circular tower, with the sky for a roof, which is seen at all the city gates. In front of us is the watchmen’s house, and the guard […] is standing in the open front of the house, but not standing as a sentinel or watchman ought to stand; his favourite position most probably is lying down, with a hubble-bubble tobacco pipe to console himself and wile away the time.’[ix]

View from the city wall towards the West Gate, Shanghai. Photograph attributed to William Saunders or John Reddie Black. Published by John Reddie Black in ‘Far East’, January 1877.

After 1909, the next landmark on the route would be the Little North Gate, or Gongchenmen (拱辰门). The postcard below shows that this section of the city wall was much lower than the eastern and southern sections, which were reinforced and augmented in different years. One instance was the disastrous flood in August 1680, when after a nightlong rainstorm, the rising waves from the Huangpu simply washed away the southern section of the city wall, toppling houses underneath it and killing several residents. The whole county was submerged in five feet of water, and ‘boats were crisscrossing Shanghai as if it was a lake.’[x] Such occasions prompted wealthy citizens to offer funds for the restoration and earn respectful nicknames, like ‘Half-the-City Pan.’

Next stop on the itinerary is the Dajing Pavilion (Dajingge 大境阁, or Guandimiao 关帝庙), known as ‘Piece-Goods Temple’ to the westerners who had noticed that ‘Chinese merchants who deal in Manchester piece-goods’ used it.[xi] Darwent’s introduction was: ‘After a quarter of a mile’s walk, we come to the Da Ching, once a guard-house or castle, now a temple. It is a very beautiful and picturesque building, and makes a splendid photograph from any point of view. Gardens and open spaces surround it; at one corner there is a pool. From that side, with the pool in the foreground, it makes a very beautiful picture.’ The photographer of the image here must have taken these instructions literally.

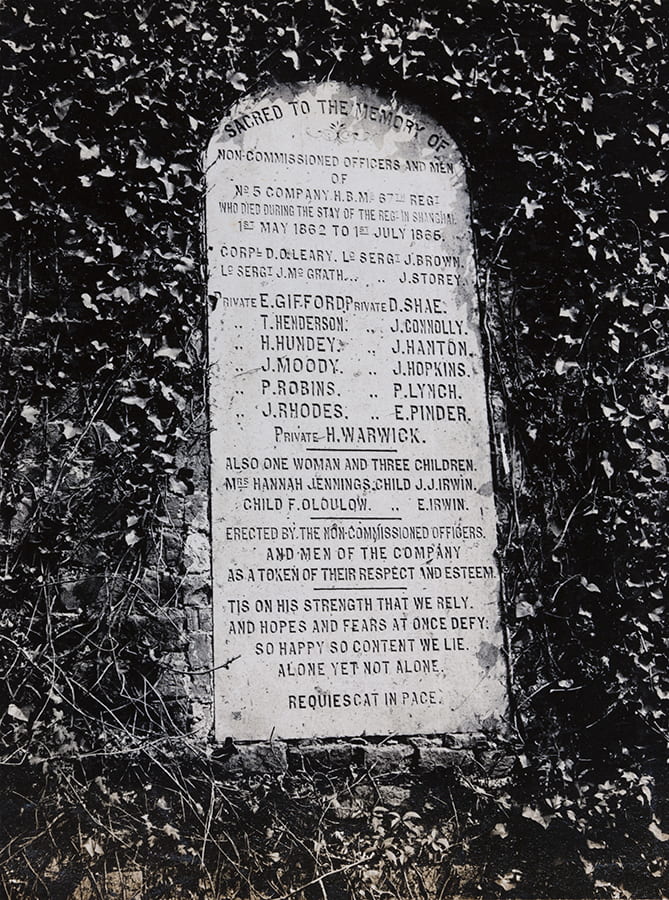

To complete the route and arrive back at the Old North Gate, one passed the Soldiers’ Cemetery on the outside of the city wall, which contained 305 graves of British nationals, who died in the 1860s during the defence of the foreign settlements from the Taiping uprising (most of these deaths were not battle casualties, but resulted from rampant cholera). Since 1887, the cemetery was virtually abandoned but three oblong memorial tablets remained embedded in the city wall until 1938, when the cemetery was finally closed and the graves relocated. The graveyard was quickly built up; new houses clung to the surviving section of the wall like barnacles and completely hid it from sight.

One of the commemorative plaques, Soldiers Cemetery, city wall, Shanghai, c.1905-1915. HPC ref OH02-15.

The city wall was torn down in the years 1912–1914, and Shanghai citizens volunteered to assist with its dismantling, salvaging the bricks to repair their houses. The earth from the rampart was used to fill the moat, and the ring road emerged in its place, with a tram running in the middle. The inner side of the ring was called Minkuo Road (Minguo Lu 民国路), and the outer, French, side was called Boulevard des deux Republiques. The subsequent editions of Darwent’s Handbook for Travellers acknowledged that the scenic walk on the rampart was no longer possible, and the temples recommended for visiting ‘have all disappeared with the walls,’ except for the picturesque Dajing Pavilion. It was rebuilt in the late 2000s to resemble the original structure and now serves as a museum of the walled city. It is surrounded by a replica wall made of black bricks, some of which were, indeed, taken from the original city wall.

Demolition of the city wall, Shanghai, c.1912. Source: Shanghai Library Archive.

The old city wall made a sudden comeback in 2006, thanks to the long-forgotten Soldiers’ Cemetery. During demolition works in this area, a seventy metre section of the original city wall was found hidden between the houses. Unwilling to change the construction agenda, the developers dismantled the discovery and only after some pressure from the municipal authorities rebuilt part of it as picaresque ruin in front of a new apartment complex.

[i] Jerry Dennerline, The Chia-ting loyalists: Confucian leadership and social change in seventeenth-century China (Yale, 1981), p. 127.

[ii] From the translation quoted in John Meskill, Gentlemanly Interests and Wealth on the Yangzi Delta (Ann Arbor, 1994), pp. 94–95.

[iii] Darwent, C. E., Shanghai: A handbook for travellers and residents… (Kelly and Walsh, 1904)

[iv] Henry McAleavy, Wang T’ao: Life and Writings of Displaced Person (London, 1953), p. 5.

[v] Yang Weizhen, Phoenix Tower Verse 丹凤楼诗 (undated).

[vi] Jiaqing Songjiang Prefecture Gazetteer 嘉庆松江府志, Vol. 10 (c. 1820).

[vii] W. Macfarlane, Sketches in the Foreign Settlements and Native City of Shanghai (Shanghai, 1881), p. 60.

[viii] George Smith, A Narrative of an Exploratory Visit to Each of the Consular Cities of China… (1847), p. 134.

[ix] Macfarlane, 1881, 28.

[x] Jiaqing Shanghai County Gazetteer 嘉庆上海县志, Vol. 19 (1814).

[xi] T. Hodgson Liddell, China, Its Marvel and Mystery (George Allen & Sons, 1909), p. 41.