Jenny Huangfu Day is the author of Qing Travelers to the Far West: Diplomacy and the Information Order in Late Imperial China(Cambridge University Press, 2018) and the editor of Letters from the Qing Legation in London [Wanqing Zhuying shiguan zhaohui dang’an] (Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2020). She teaches East Asian history at Skidmore College, New York.

In the decade before the Qing established its first legations in Europe and the United States, it sent out a few investigatory missions staffed with mid-level officials to prepare for the dispatch of long-term resident ministers. The gentleman who led the first mission of 1866 was Binchun, a retired magistrate with personal connections to the Zongli Yamen, the newly created central office to handle foreign affairs. In Qing Travelers to the West, I wrote about how members of the Qing’s early missions imagined, poeticized, circulated, and consumed information about the West, and how these earlier strategies of conceptualizing the West changed when the permanent legations were established.

Figure 1: Cover image of ‘Qing Travelers to the Far West’.

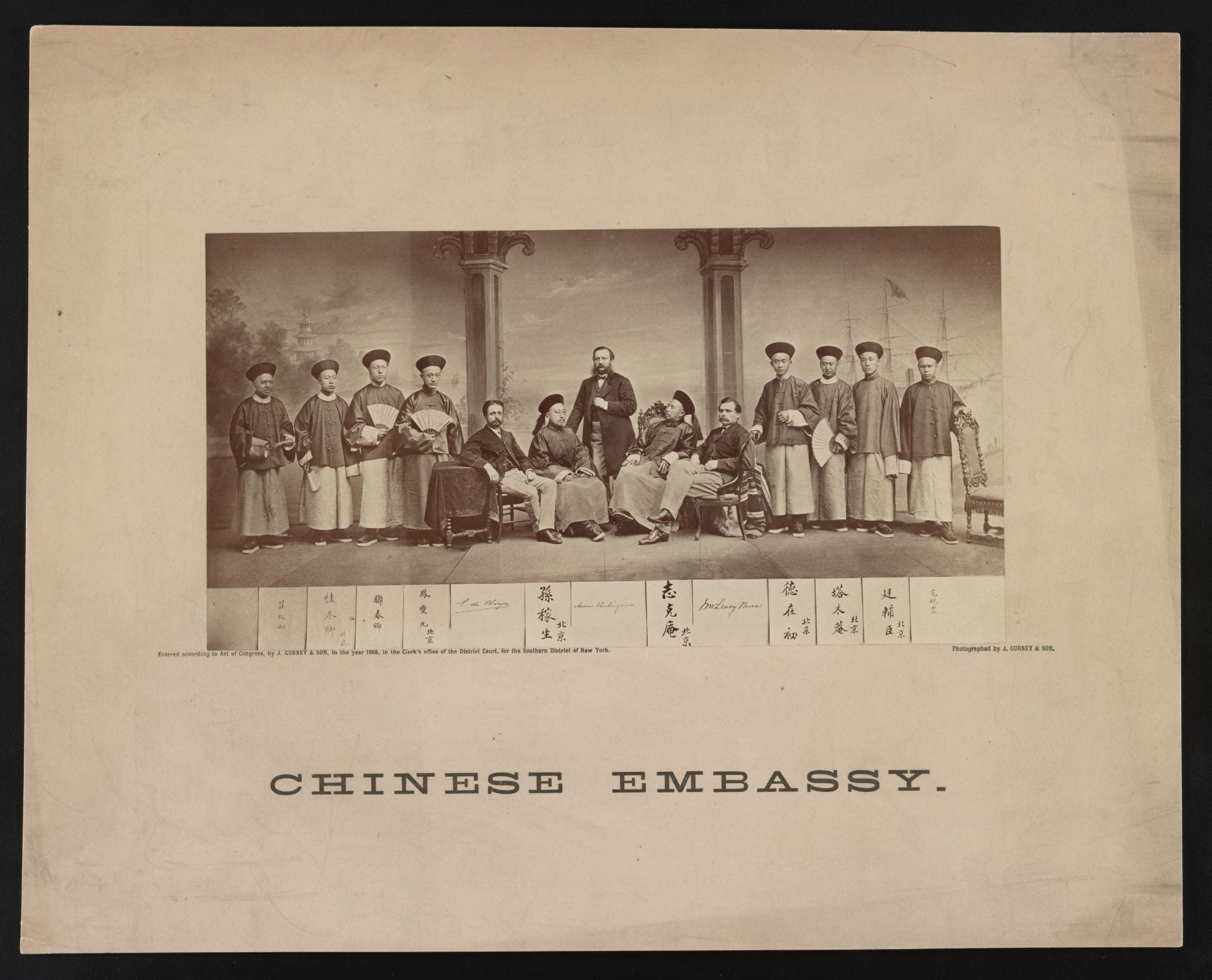

Just as the Chinese used these travels to gather information about the West, Western depictions of these early missions – in sketches, photographs, watercolour paintings, and texts – made rounds in metropolitan and local newspapers and some were exchanged in private collections, making them excellent sources in what nineteenth-century Europeans considered important about the Chinese.

Before we examine some of these images and texts, it’s worth mentioning that Binchun and his colleagues were quite aware that they were being documented in Western media, even though they might not be clear just how they were being portrayed and why the Europeans held such a fascination with their images.

Binchun wrote in his journal: ‘Months before our arrival, newspapers of each country began making noises, and when we are here, many people ask to see us or make sketches of us. A few days ago when we were in Paris, merchants kept the films of our photographs and sold prints at fifteen silver dollar per portrait.’[1] His poems attributed the attention they received to his own charisma and the civilizing influence of Chinese culture, and he used the mission’s popularity to forge important personal connections. The Chinese were not being passively observed, but negotiated their appearances and to the extent possible, positioned themselves in ways to take advantage of it.[2]

British journalists subjected the mission to constant and minute scrutiny, but for quite different purposes from what Binchun seemed to think: it was important to know exactly what the ranks of the Chinese were in order to know what level of accommodation they were entitled to. According to the Birmingham Daily Post: ‘The study of buttons is essential to an accurate appreciation of Chinese life … We have scanned their costumes from their skull cap to their thick-soled shoes; and round the outside of their flowing robes, back and front, without being able to discover the all-important sign of rank about them.’ Speculations about the precise ranks of the commissioner and his suites occupied the British press in the few days, and the ‘great mystery’ was eventually solved after members of the mission made a formal appearance in official attires, complete peacock feathers and buttons.

Visual portrayals of the mission confirmed the anxiety about the status of the Chinese, highlighting the features mentioned in Birmingham Daily: notably, their officials robes, the peacock feathers and ‘button’ decorating the commissioner’s hat, the court beads, the embroidered symbol marking one’s place in the official hierarchy, the woven waist-sash. All members of the mission were depicted with their long, braided queues made emphatically visible.

Figure 2: Binchun and the Tongwenguan students at a French salon, 1866, Le Monde illustré, May 19, 1866.

Indeed, to have their peacock feathers shown, Qing commissioners were probably often asked to look sideways when being photographed in studios, instead of gazing directly into the camera and engaging the eyes of the beholder. This visual strategy can be seen in many well-publicized photographs the early missions.[3]

Figure 3: A portrait of Binchun, ca. 1866, courtesy of Tong Bingxue.

Figure 4: Anson Burlingame with two Chinese co-envoys, Zhigang and Sun Jiagu, and the Tongwenguan students, courtesy of Library of Congress.

Whether intended or not, such visual strategies of portraying the Chinese in their early missions to the West confirmed many existing impressions about the Chinese: that they were extremely status-conscious, fond of social gatherings, and typically gave only somewhat innocent – if not childish – responses to what they saw, depicted by terms such as ‘delighted,’ ‘disappointed,’ ‘disapproved,’ or ‘taken aback.’ In the following image, taken in Stockholm, the juxtaposition of the Qing mission, seen as a moving relic of an ancient and static culture – and the monumental glass-roofed ‘crystal palace’ at the Kungsträdgården, an industrial hall designed by the great architect Adolf W. Edelsvärd, sums up these impressions well.

Interestingly, these caricatures of the early Chinese travellers to the West, simplistic and condescending as they were, have been embraced by modernist Chinese intellectuals in the reform era – and at present – to show how far China has come along, or has yet to go, towards becoming ‘modern.’ Images of these early travellers to the West, created through the lenses of nineteenth century Western photographers, came to embody the steps China took to walk out of its supposed late imperial isolation and arrogance. Whatever its historical validity, the trope of the Confucian gentleman ‘stepping forth onto the world’ has been widely circulated in the Chinese public sphere, often as a subtle critique of the nationalist, or anti-Western, policies of the People’s Republic of China.

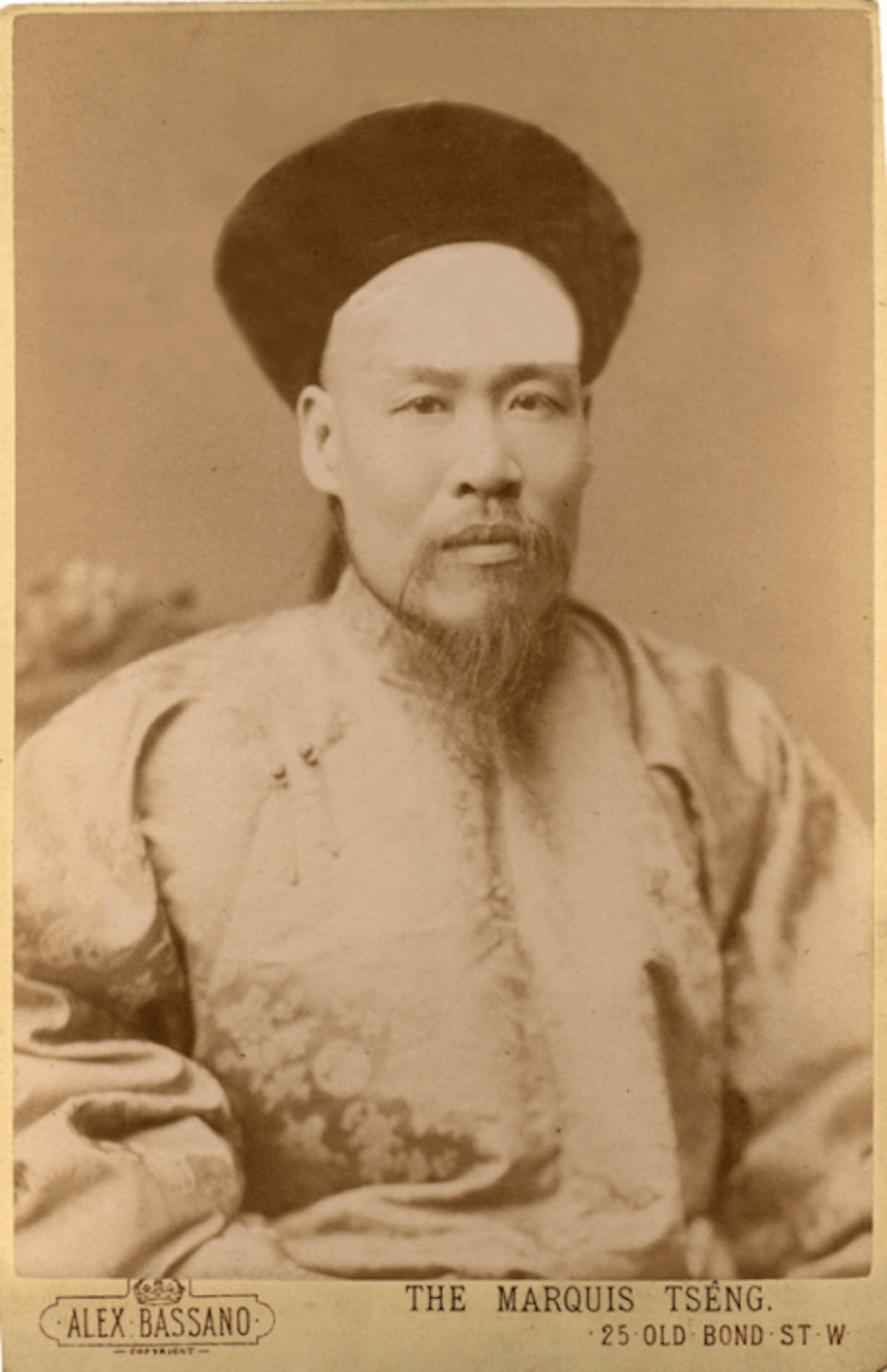

As Qing diplomacy converged with contemporary Western practices and moved towards the permanent legation, the value of Qing representatives as spectacles of the orient also declined, as it was replaced with direct consultations with Foreign Ministries. The role of the diplomat thus differed fundamentally from that of the traveling mandarin by design. Diplomatic negotiations were often conducted in private meetings, in writing or through telegraphy, with little fanfare and publicity. From 1877 onward, the most publicized images of Qing diplomats were standard head portraits similar to those of European statesmen, not visual stories exhibiting them on site.

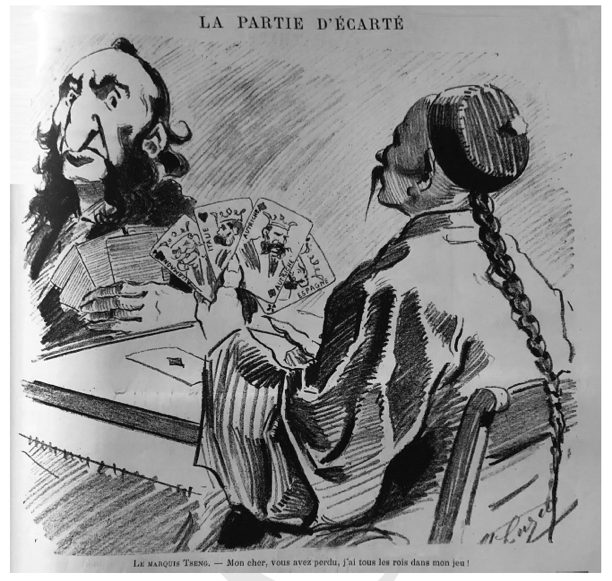

From the 1880s onward, hardly any visual representation of Qing diplomats could be found in Western newspapers, and when they appeared, the Chinese were not depicted as spectators, but as diplomats and statesmen.

Figure 6: Portrait of Marquis Tseng (Zeng Jize), early 1880s, courtesy of Tong Bingxue.

Figure 7: French political cartoon depicting Zeng Jize playing cards with Jules Ferry as an allegory of their intense negotiations in the months leading up to the Sino-French War. ‘Le monde parisien’, 1883.

So the image of the traveling mandarin gazing the West in wonder came to an end with the Qing’s dispatch of resident ministers and consuls. This change was as much a reflection of China’s changing diplomatic structure, as it was a media artefact of how the Chinese came to be documented by the press.

[1] Binchun, Cheng cha biji (113.

[2] Day, Qing Travelers to the Far West: chapter 1.

[3] I argue that the name ‘Burlingame Mission’ has tended to downplay Chinese agency in the mission.