Dr. Ning Jennifer Chang is an Associate Research Fellow at the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. She has just published her first book, Cultural Translation: Horse Racing, Greyhound Racing and Jai Alai in Modern Shanghai (異國事物的轉譯:近代上海的跑馬、跑狗與回力球賽). Here she introduces the book and its main arguments.

Cultural Translation explores how culture was ‘translated’ through a study of three imported Western sports/gambling in the colonial setting of Shanghai. They were, namely, horse racing, greyhound racing and jai alai (also known as Basque Tennis). The book shows these sports all experienced deviation and re-interpretation in China in very different ways.

Cultural Translation explores how culture was ‘translated’ through a study of three imported Western sports/gambling in the colonial setting of Shanghai. They were, namely, horse racing, greyhound racing and jai alai (also known as Basque Tennis). The book shows these sports all experienced deviation and re-interpretation in China in very different ways.

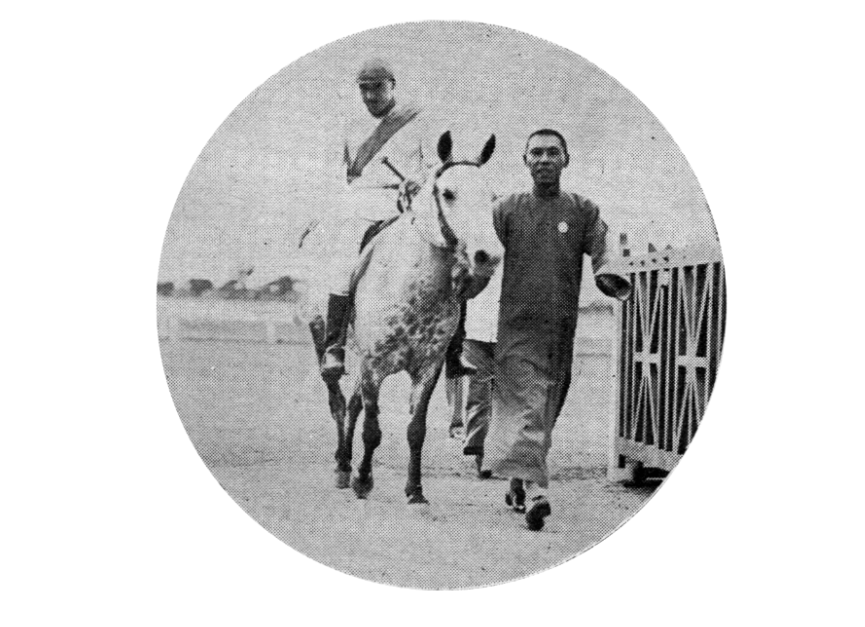

A man leading a horse past the ‘CASH SWEEP’ betting booth, Peking races, Beijing, c.1925-26. Oliver Hulme Collection, OH02-62.

Historical Photographs of China contains a great many photographs of racing life, with images of racing and race days at Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Tianjin, Qingdao and Hankou. Racing was a leisure activity, but it was also about display and it was a business. As the photograph above of a horse being led by its owner at Beijing’s race course in about 1925 indicates, it was also about gambling: the windows in which racegoers could enter the Cash Sweep can be seen in the background.

Tiffin on the re-opening of the Chinese Jockey Club in Oct. 1935. (Quan Guo Bao Kan Suo Yin (Source: cnbsky.cn))

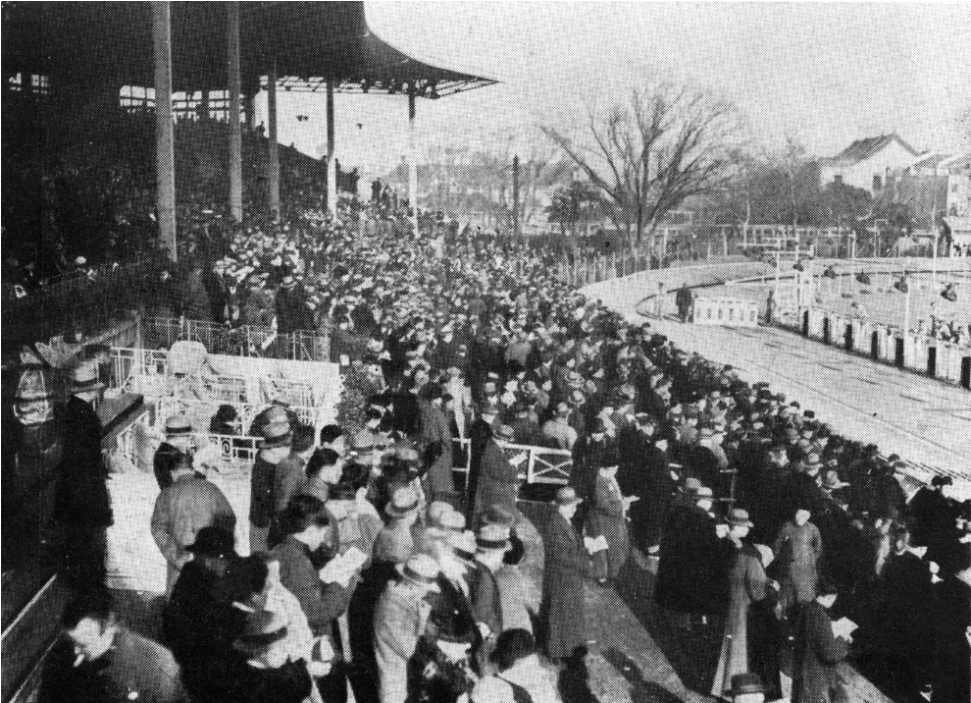

We know that racing clubs played a prominent role in the colonial world but less well-known is the fact that not only the Chinese elite, but underworld figures such as the leaders of the Green Gang saw such clubs as tools for social navigation. After the establishing in Shanghai of first an International Racing Club, at Jiangwan, and later a Chinese Jockey Club, they became proud club members. When joint meetings between the clubs were held, British gentlemen had to rub shoulders with Chinese gangsters. The class identities of the British club were thus redefined to an unknown degree.

Famous gangster, Du Yuesheng, leads in Merry Memories, winner of the Ladies Purse at the Chinese Jockey Club meeting on 6 June 1935. (cnbsky.cn)

Madame Du presents the Ladies’ Purse to Charlie Encarnacao, the winning jockey. (cnbsky.cn)

No doubt quite a few of the Chinese elite and even gangsters embraced British racing culture. Not only did they follow British rules strictly, they registered their clubs at Newmarket in England to prove their authenticity. When examining spectator behaviour in these sports, however, my work has revealed a gradual development in spectator behaviour from watching to betting. When jai alai was staged, spectators even found a way to Sinicize it. They managed to establish a forecast theory by borrowing from traditional Chinese betting knowledge, leaving Western theory of probability no room to act.

Afternoon greyhound racing in Shanghai. (cnbsky.cn)

Betters watch jai alai attentively from behind the wire netting. (cnbsky.cn)

By demonstrating this deviation and re-interpretation, this book argues cultural translation was not a simple phenomenon of localization. Instead, it was a result of a complex seesaw battle between cultures. The direction and degree of its deviation depended on how powerful the cultures were. For example, China had a longer and stronger tradition in gambling, so the spectators managed to re-interpret these sports in the Chinese way. On the other hand, the British empire no doubt played a more important role in the colonial setting in Shanghai. The British way of racing captured the attention of the Chinese elite and even gangsters.