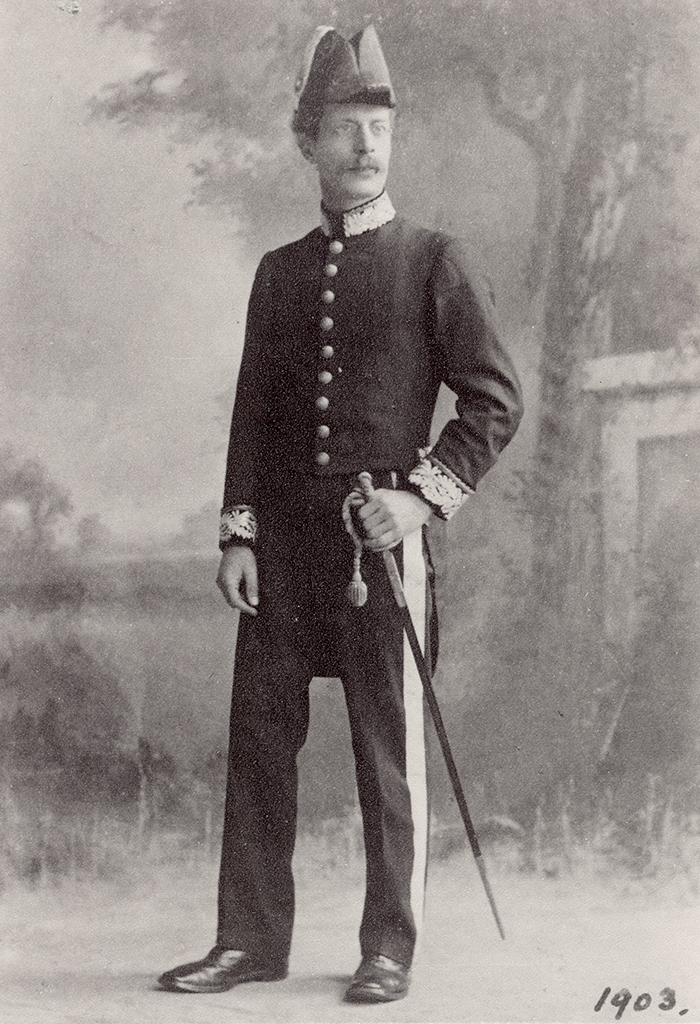

Dr Andrew Hillier has been looking at the unpublished letters of a British Student Interpreter, later Consul, Walter Clennell. The correspondence highlights the importance of photography to Legation life in Beijing in the late 1880s. Andrew recently completed his PhD at the University of Bristol.

‘The photography goes on unchecked in the Legation. Mrs Wingfield, the two Walshams, Mortimore and Brady are all constantly at it, if it is not too cold, and they talk of very little else when they are indoors’. So wrote the student interpreter, Walter Clennell, in one of a number of letters sent home during his first eighteen months in Peking, in 1888-89, in which he enthused about this new hobby and enclosed copies of the photographs he had acquired. Whilst none of those pictures have been traced, the letters provide important evidence of how amateur photography became a popular pastime amongst the Legation staff in the late 1880s in a way which has been little recognised until now.[i]

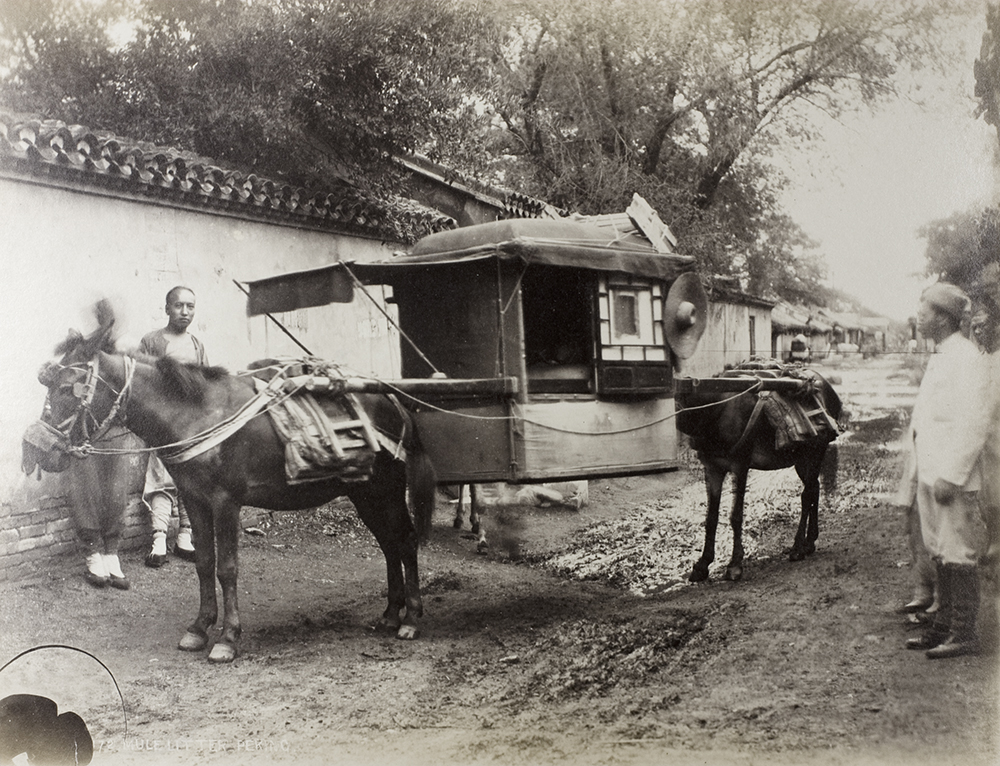

Although we do not have the pictures, we do know where Clennell was able to buy many of them: in one letter, he explains how he had asked Mr Child if he could ‘look over his collection. He had about 200, all views of the city, or neighbourhood as far as the Great Wall. A good many were interesting enough.’[ii] By this time, Thomas Child had long established his reputation as more than just an amateur photographer but was about to leave his job as a gas engineer in the Chinese Maritime Customs and return to England with his family. Having made his selection, Clennell inserted them into lengths of bamboo, in order to keep them safe and dry, even if this meant they had to be unrolled and smoothed out on arrival. [iii]

1. Mule litter, Peking, estimated 1870-1890. An unusual example of Thomas Child’s Peking photographs in showing street life. National Archives Collection, NA01-91 © Crown copyright 2011

Whilst we cannot be sure, it is possible that that this enthusiasm had been prompted by the arrival of ‘the Kodak’, the camera which George Eastman had brought onto the market in August the previous year, accompanied by the slogan ‘You press the button, we do the rest’.[iv] Given the numbers of people taking pictures and the ease with which they were doing so, they must certainly have been using an ‘instant camera’ with film rather than glass plate negatives. Portable and easy to operate, this new device could be taken on walks through the city and expeditions further afield. As the North China Herald pointed out when suggesting it as a Christmas present the following year, ‘At this time … when so many people go up country, photographic cameras are very handy’.[v] Another of Clennell’s letters describes how ‘the three Irishmen of Peking, Messrs Jordan, Oliver and Brady, went on a trip to the Ming Tombs and ‘Brady took six photographs’.[vi] Herbert Brady, the Legation’s accountant and Chief Assistant had already amassed a considerable collection and would eventually compile two albums of pictures spanning his years in the consular service.[vii]

Clennell mentions a number of other talented amateur photographers in Peking at the time. Dr Dudgeon, whose family he came to know well, had already established himself as an expert, publishing a book in Chinese on how to take photographs. However, the letters make no reference to him taking any pictures, which is frustrating since, as Nick Pearce says, there is little evidence of Dudgeon ever actually using a camera’ although it is clear he did so. [viii]

2. Street in Peking. Photograph by Walter Hillier. Probably taken in the late 1880s before Hillier’s appointment as Consul-General to Korea in 1890 (Royal Geographical Society, SOOO25562).

Walter Hillier, the Chinese Secretary, whom the spell-bound Clennell ‘supposed was probably the greatest Chinese scholar that the English race has produced’, also had a substantial collection, including ‘some grand photographs of places near Darjeeling, amongst them the only photo of Mount Everest that has ever been taken (seen from nearly a hundred miles away)’.[ix] Whilst he had obviously purchased these pictures, Hillier was also a keen photographer, later using coloured lantern slides to illustrate his talks about China and Korea, which he gave following his retirement from the Consular Service in 1896.[x]

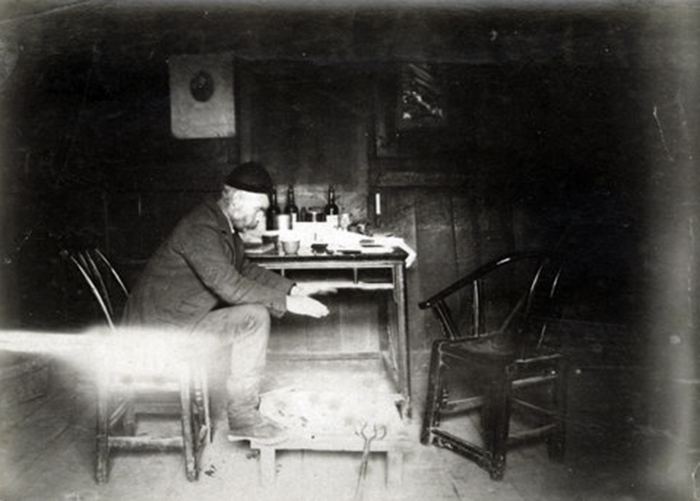

Hillier’s brother, Guy, whom Clennell met shortly after his appointment as the Hongkong Bank’s Peking agent, took a number of photographs with an instant camera when visiting a remote monastery in the mountains of south-west Ichang – ‘the wildest and most desolate place I have ever found myself in’, as he described it in a talk read to the Manchester Geographical Society later that year (see plates 3 and 4).[xi]

3. The Mission Station at Szu ku-shan: Father Braun and some of his flock, 1890. Photograph by Guy Hillier (Author’s collection).

4. Guy Hillier’s travelling companion, Gordon, warming himself at the fire. Photograph by Guy Hillier. (Author’s Collection).

Clennell’s letters reflect not only a general enthusiasm for photography amongst the Legation staff but also the way the hobby cemented what was obviously an easy-going atmosphere at all levels. The Minister, Sir John Walsham, and his wife seem to have had an unusually relaxed approach, there is little sense of hierarchy and family life thrived, with the Legation children being both seen and heard, and pastimes, including skating, shooting, amateur theatricals and fancy dress balls, being captured in photographs.

In one letter, by way of ‘a birthday present for Papa’, Clennell inserts ‘two photos of the Legation people’ with captions. In another, he describes having dinner at Brady’s which was ‘as nice an entertainment as could be wished’; apart from his ‘almost endless collection of photographs’, he kept ‘a very pretty “bachelor’s” house’, albeit not for much longer, as, by the end of the year, he would become engaged to Gina Hole, the half-sister of Walter Hillier, a romance which Clennell observed with interest, if not envy, describing her as ‘a very nice young lady of about twenty, of the jolly, communicative sort’. [xii]

5. The ‘jolly and communicative’ Gina Marshall Hole, photographed shortly before leaving for China in 1888. She later married Herbert Brady. Photograph by Boning and Small. Andrew Hillier Collection, Hi-s143, © 2014 Andrew Hillier.

6. Consul Clennell, 1903. (Private Collection).

The enthusiasm also reflects the interest being taken in Peking as a city, which, despite its drawbacks – the dirt, the smell, the dust in summer – Clennell found fascinating, describing how, in one of the photographs he sent home,

you see the Chinese city, with the Temple of Heaven right away in the distance to the left, and the top of a gate to the right. There is a rather good specimen of a wooden p’ailou, or arch, over the street. There are p’ailous in nearly all the chief streets, with inscriptions in Chinese and Manchurian. The street itself is rather characteristic too, with booths and stalls along both sides.[xiii]

In the main, however, the Chinese do not feature in these pictures. Child tended to concentrate on buildings rather than street life and the relationships which Clennell describes are cordial but remote, with even his teacher refusing to acknowledge him if they should meet in the street. Nonetheless, it was a time when Sino-British relations were slowly beginning to improve and, whilst professional photographers such as John Thomson had already published substantial collections in England, the practice of enclosing photographs in letters home, glossed with detailed narratives, was an important and novel way of visualising Britain’s presence in China on a more intimate level.[xiv]

However, this relaxed atmosphere would not last, China’s defeat by Japan in 1895 heralding a more aggressive approach by the Western powers, which ultimately led to the Boxer Uprising. Whilst those events would also be recorded in detail, the images would be of a very different character to the ones which the young and enthusiastic Walter Clennell sent to his family in his early days in Peking.

[i] Letter, Walter Clennell to his sister, Trixie (Beatrice), 21 December 1889, Walter James Clennell, ‘Destination Peking: A Young Man’s Journey into China, 1888 – 1889’, unpublished manuscript, 2008 (Private Collection), at p. 341. I am very grateful to Jonathan Clennell for allowing me to draw on these letters and to reproduce the photograph of Walter Clennell.

[ii] Letter, Clennell to Trixie, 22 February 1889, at p.186.

[iii] For details of Child’s life and work see Regine Thiriez, Barbarian Lens: Western Photographers of the Qianlong Emperor’s European Palaces (Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach Publishers, 1998), pp.75-84, Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China: Western Photographs, 1861-1879 (London: Quaritch, 2010), pp. 56-78; see also Historical Photographs of China, https://www.hpcbristol.net/photographer/child-thomas.

[iv] Helmut Gernsheim in collaboration with Alison Gernsheim, The History of Photography: from the camera obscura to the beginning of the modern era (London: Thames and Hudson, 1969), pp. 405 and 413.

[v] ‘Christmas Show at the Stores’, North China Herald, 13 December 1889, p.726 and see also 20 December 1889, p.758. I am grateful to Terry Bennett for this reference and for his comments generally.

[vi] Letter, Clennell to his brother, Harold, 12 February 1889, at p. 182; see also https://www.hpcbristol.net/visual/na01-68.

[vii] Herbert Francis Brady, Bo Ian Zhonghua tu zhi (Pictorial Journal of Viewing China), c. 1873-1906, Getty Research Institute, http://primo.getty.edu/GRI:GETTY_ALMA21127096190001551; cf. Jeffrey Cody and Frances W. Terpak, Brush & Shutter: early photography in China (Exhibition, 2011: Los Angeles, Calif., J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles, Calif.: Getty Research Institute, 2011), p.40 and Plates 22 (Kiang-si Guild, Hankou) and 23 (Chinese Actors and Fire Brigade, Peking).

[viii] Touying qiguan; see Chen Shen et al., Zhongguo shying shi (A History of Chinese Photography) (Taibei: Photographer Publications, 1990), pp.65-66, Nick Pearce, ‘A Life in Peking: The Peabody Albums’, History of Photography, 31 (2007), pp. 276-293 and Bennett, History of Photography in China, pp.37-55; see also https://www.hpcbristol.net/photographer/dudgeon-dr-john and https://www.hpcbristol.net/visual/os03-056.

[ix] Letter, Clennell to his mother, 28 December, 1888, at p.143.

[x] See Collection of Sir Walter Hillier, Royal Geographical Society Picture Library.

[xi] Guy Hillier, ‘A Mountain District of Central China’, Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society 6 (1890), pp. 370 – 380. For the Hilliers in China, see Visualising China Blog, my post, 22 September 2016.

[xii] Clennell to Harold, 5 December 1888 at p.124.

[xiii] Letter, Clennell to Trixie, 26 February 1889, at p.186.

[xiv] John Thomson, Travels and adventures of a nineteenth century photographer, with an introduction and new illustration selection by Judith Balmer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993); cf. Robert Bickers, The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914 (London: Allen Lane, 2011), pp. 218-20).