Andrew Hillier discusses a diary, a photograph album and a memoir which, between them, provide a fascinating insight into consular life as well as showing how such materials can be used for exploring histories of intimacy and the emotions.

The figure in the centre of the photograph (fig. 1) does not look like a typical British Consular wife. Flanked by five armed marines, she smiles jauntily, with her head tilted to one side, and holds her parasol as though it is a fashion accessory. This is Mabel Kirke, wife of the Swatow (Shantou) Consul, Cecil Kirke, but, if it is all meant to look rather amusing, the situation was in fact very serious, as the caption indicates. For well over a year, anti-foreign activists and union strike-leaders had seized control of Swatow and brought its life to a standstill.[1]

Fig 1. MX [Mabel Kirke] with armed guard from HMS Hollyhock, 1926, during the strike at Swatow. Unknown photographer. Cecil Kirke Album. Copy courtesy of the Kirke Family.

Whilst the detail of what went wrong and why may only be of interest on a private level, the story is important for what it tells us about consular wives, given the important role they played in treaty port life and the lack of attention that has been given to them in the literature.[3] The outline can be traced back to the time when, home from China and meeting Mabel whom he had known and loved from afar for many years, Kirke proposed.

I was longing to ask her to be mine but was so stupidly afraid that I do believe I should not have done it had I not seen plainly that she wanted me to.[4]

He was right and she accepted. He was twenty-nine, and she was thirty. Eight months later, on 29 November 1904, they were married in Alnwick, Northumberland and soon afterwards sailed for China.

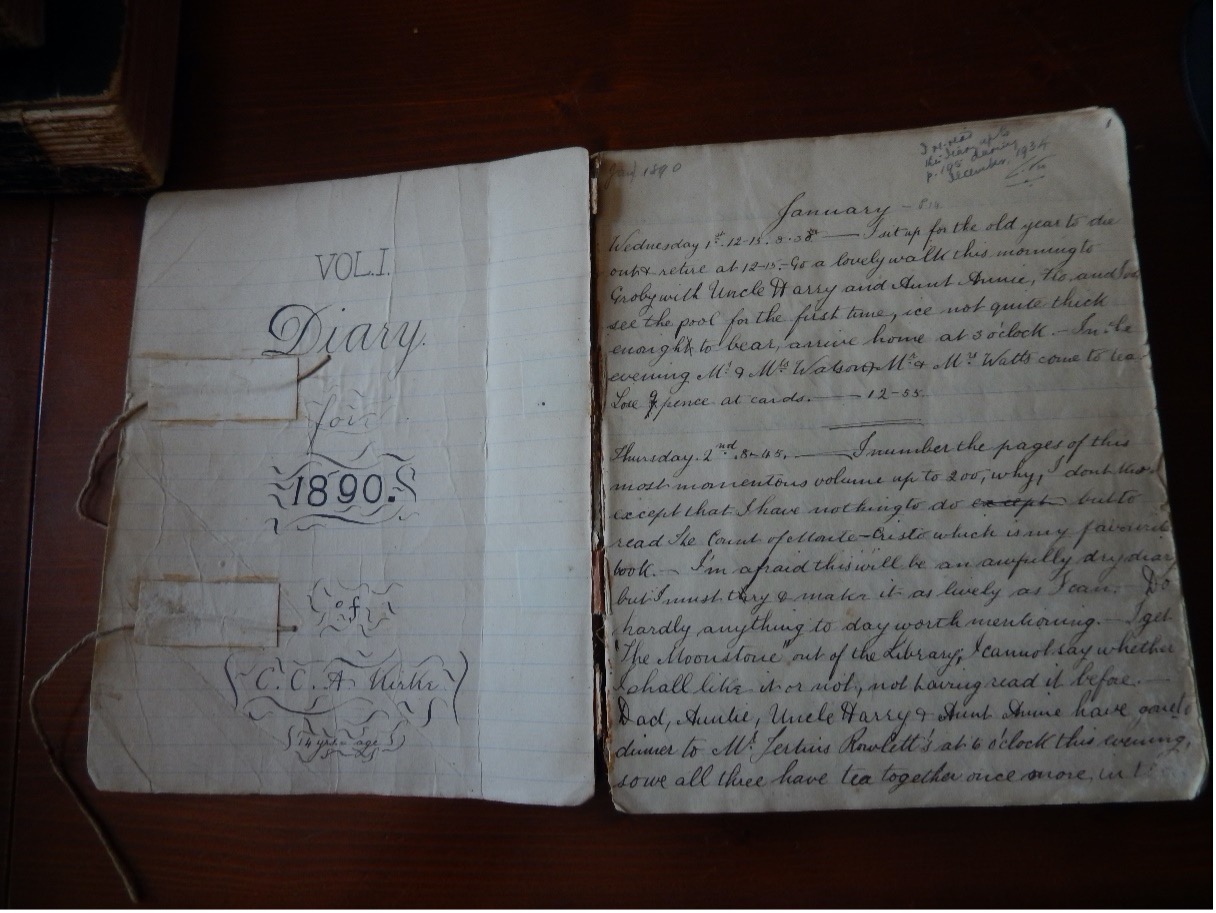

Begun when he was fifteen, and running to some eight thousand pages, the diary is an extraordinary document, reflecting Kirke’s tortuous inner life and putting it under the microscope in a way which renders him both analyst and patient; all the more extraordinary, given that the concept of analysis was still in its infancy in the early 1900s.

Fig 2. The Diaries. Author’s photograph, 2021

Fig 3. The first page of the diary begun on 1 January 1890 when Kirke was fifteen. Author’s photograph, 2021

Having joined the consular service in 1898 as a Student Interpreter, Kirke had survived the Siege of the Legations – a time he later described as ‘one of the most interesting events of my life’ – and, although he always found Chinese difficult, he would have a successful career and, through his skilful handling of the Swatow crisis, be awarded a CBE. With the exception of the Siege, which he describes in the insouciant tone characteristic of almost all the accounts, his public life is only lightly sketched in and there is little or no discussion of consular matters in the diary. It is his private life which is important, and of course not just his but that of those closest to him – Mabel, who is subjected to a continuous and rigorous critique, of their four children and, perhaps most important of all, of his younger sister, Iva, with whom he maintained a regular correspondence throughout his time in China. With their mother dying weeks after her birth, it was this relationship, forged as it was during an otherwise lonely childhood, which would mean more to Kirke than any other. Supplemented by an album of photographs, we can piece together the intimacies of his consular life.[5]

And, although we cannot hear Mabel’s voice, Kirke is sufficiently honest and insightful for us to obtain a fair view of her character and of some of the problems she had to contend with as a consular wife. High-spirited but perhaps unsuited to the formalities of the diplomatic and consular world, her early married life was dogged by misfortune. Suffering terrible sea-sickness on the outward journey, she then had what he describes as ‘a partial miscarriage’, which was only detected four weeks after their arrival in Shanghai and necessitated an emergency operation to remove the remains of the foetus. Struggling to recover, she had to adapt to the strict protocol and oppressive climate of Peking, where Kirke had been appointed the legation accountant. Socially insecure himself, he did nothing to make things easier for his wife, for whom the hierarchical structure proved extremely daunting, partly due to the personality of the incumbent Minister, Sir Ernest Satow, whom Kirke found ‘portentously cold and almost inhuman’.[6] Subsequent years were spent in various locations including what was a reasonably happy period at Chefoo just before the First World War (see fig.4).

Fig 4: Original caption: ‘Chefoo, 1913’. Unknown photographer. Cecil Kirke Album. Copy courtesy of the Kirke Family.

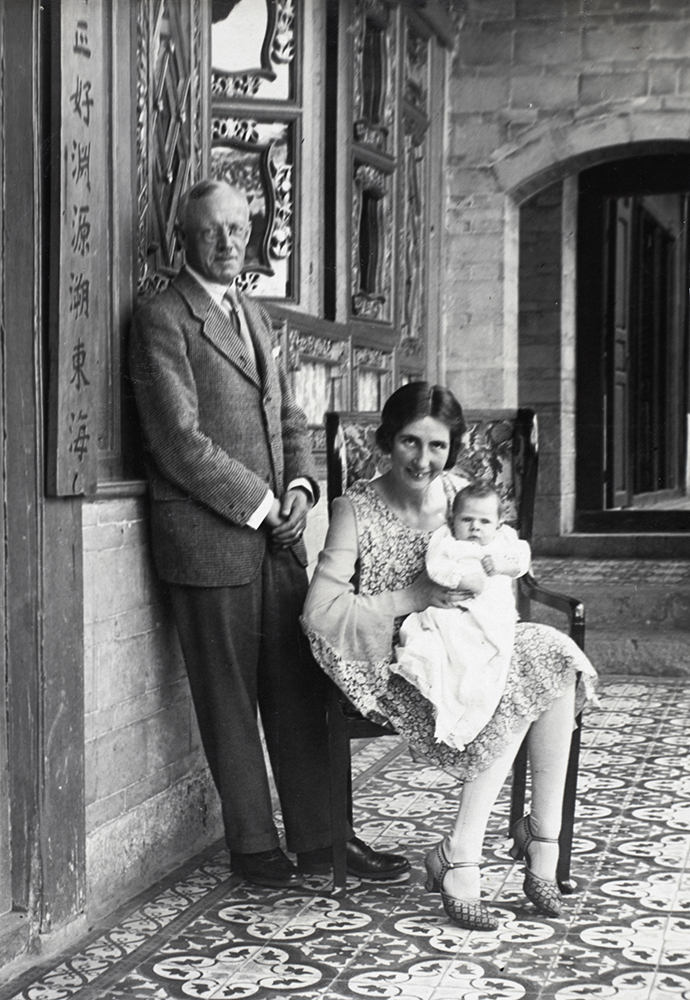

But those early difficulties seem to have taken their toll, causing Mabel to lose confidence and a barrier to come between them, in a way which Kirke analyses in disturbing detail. However, whilst he describes the froideur of the last ten years, he does not suggest it was explicit or that it led to arguments, tears and recrimination. So, it is just possible that Mabel was unaware of his inner torment and was, as she appears in the first image, fun-loving and carefree. But the probabilities are that the cold formality of the photograph taken four years earlier provides a more accurate picture. (fig 5).

Fig 5: RHS Kirke, Mabel & child, Chefoo

Unknown photographer. Cecil Kirke Album. Copy courtesy of the Kirke Family.

Returning to China a year after Mabel’s death, Kirke was promoted to the post of Consul-General in Yunnan-Fu. There he met and married Sybil Esme Sandys, a missionary twenty-five years his junior. She had devoted herself to rescuing Chinese girls and women from the practice of ‘slavery’ which still existed in the region. She had successfully enlisted Kirke’s help in obtaining a safe home for them and it may have been this that convinced her to accept his proposal. Once again, according to his diary, he was very much in love and with Sybil’s dedication to the missionary cause and his support for that cause, the first three years were happy, including as it did the birth of their first son, Malcolm.

Fig 6: ‘Yunnan-fu 19.v.30’. Cecil, Sybil and Malcolm Unknown Photographer. Kirke family Collection

However, in 1932, Kirke decided to retire and, having returned to England, this early promise would not be fulfilled. He always worried about money and, with only a relatively small pension to live on, these worries increased when five years later, to their mutual surprise, so they would say, Sybil became pregnant and their second son, Anthony, was born. Although she remained very active and continued to devote herself to worthy causes, nothing quite engaged her as much as her missionary work in China, as she made clear in a memoir written towards the end of her life.[7] And, in that memoir she also talks about her marriage. Soon after arriving in England, she met Cecil’s sister, Iva, and immediately realised that she and Kirke were ‘twin souls’, that nothing could come between them and that their relationship, albeit conducted by correspondence, was a key reason why his marriage to Mabel had failed. Although she raised this with Cecil, he could not accept that there was a problem. It soon became clear that the same would apply to their marriage and that it would never take precedence over his relationship with Iva. From then on, although they stayed together, they drifted apart emotionally. Kirke died in 1959 and, retiring to her beloved Lake District, Sybil survived him for a further thirty years.

Family life played an important part in the British consular world, particularly in the more remote treaty ports, where the consul’s wife had an important role to fulfil.[8] If at times, Kirke’s morbid introspection becomes oppressive for the reader, it is important for an understanding of the impact it had on his two wives, Mabel and Sybil. Although this essay can only skim the surface, the diaries, taken with the photograph album and Sybil’s memoir, present, I believe, a unique record not only of these intimate lives but also of the impact that those lives may have had in that world.

My Dearest Martha: The Life and Letters of Eliza Hillier, edited by Andrew Hillier, was published in August by the City University of Hong Kong Press. Andrew is currently carrying out research for a book on China Consular wives.

https://www.andrewhillier.org/

[1] Sybil Kirke, undated memoir (25 pages); Kirke Family Collection.

[2] Cf. Andrew Hillier, An English Family in China: 1817-1927 (Folkestone: Renaissance Books, 2020), xxvii-xxviii; xxix-xxxii.

[3] The album has been digitised and will in due course appear as the Kirke Collection on Historical Photographs of China.

[4] Kirke, diary entry, 4 March 1906, vol. 7, p.311.

[5] P. D. Coates, The China Consuls: British Consular Officers, 1843-1943 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 464-467.

[6] The fifteen volumes of the diary remain in the possession of the Kirke family. I am extremely grateful to Anthony and Judith Kirke, and to their son, Jeremy, for affording me access to the diaries and for all the help they have given me in my ongoing research into this story.

[7] Cf. Coates, China Consuls, pp. vii and 99-100.

[8] Cecil Kirke, diary entry, 19 March 1904, vol. 6, p.912.