Andrew Hillier considers how five portraits of the London Missionary Society (LMS) missionary, Walter H. Medhurst (1796-1857), one of which can be found on HPC, made over the course of his career, were used to maintain connections and promote the missionary cause.

Devout evangelical though he was, Walter Henry Medhurst was not above a touch of vanity, particularly when it came to sitting for his likeness. At least five examples survive today, together with a number of contemporary copies. Between them, they show how he and the LMS attached importance to the image, both for the purpose of promoting the missionary cause and as part of the LMS archive. With his forty-year career coinciding with the birth of photography, they also demonstrate the increasing importance of that new medium for such exercises.[1]

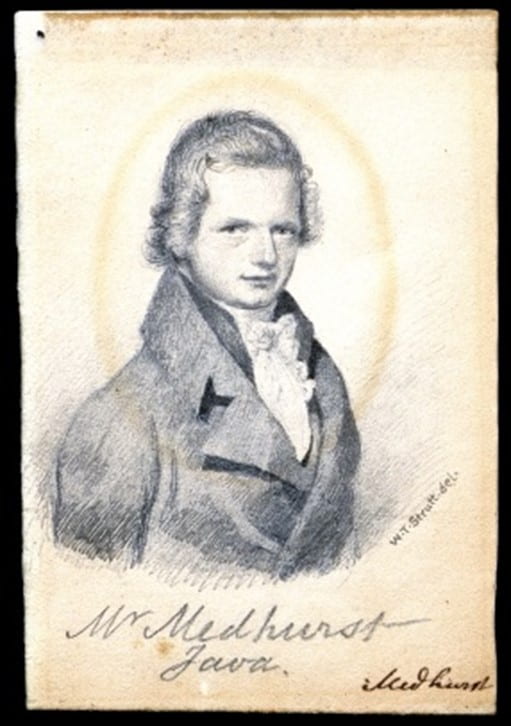

Appointed as a missionary printer to the newly established station at Malacca, on 30 August 1816, aged just twenty, Medhurst, set off on the first leg of his journey to Madras. Before doing so, the LMS commissioned the miniaturist, William Thomas Strutt (1770-1850), to make a portrait of its latest recruit, to form part of its growing collection.[2] Wearing attire chosen to match the age of elegance, Medhurst comes across as more Regency buck than zealous missionary. No doubt it was this and a dogged persistence, that would become legendary, that persuaded his future wife, Betty Braune, to accept his proposal of marriage shortly before he was due to leave Madras. The following day, with the formalities completed, the happy couple set sail.[3]

Fig. 1. One of two identical portraits in Archives and Special Collections, SOAS, the first with just ‘Mr Medhurst’ written on it and this one, with ‘Mr Medhurst Java’ added at a later date. The portrait was done by W.T. Strutt before Medhurst left England in 1816. Archives and Special Collections, SOAS ref: CWM/LMS/Home/Miniature Portraits/Box 11 (CWM/LMS/01/09/01/05A).

After five somewhat turbulent years in Malacca and, briefly, Penang, Medhurst was dispatched to Batavia, Java. There he spent the next twenty years, travelling far and wide, and, having mastered a number of dialects, preaching to the expatriate Chinese in preparation for entering the country itself. Although he achieved few converts, during a two month expedition up the China coast in 1835 he convinced himself that, despite fierce official opposition, the country was ‘ready for the Gospel’ and, the following year, he returned to England to publicise the cause. Over the next two years, Medhurst toured the country, addressing packed meetings and raising substantial funds for the intended conversion of China’s many millions.

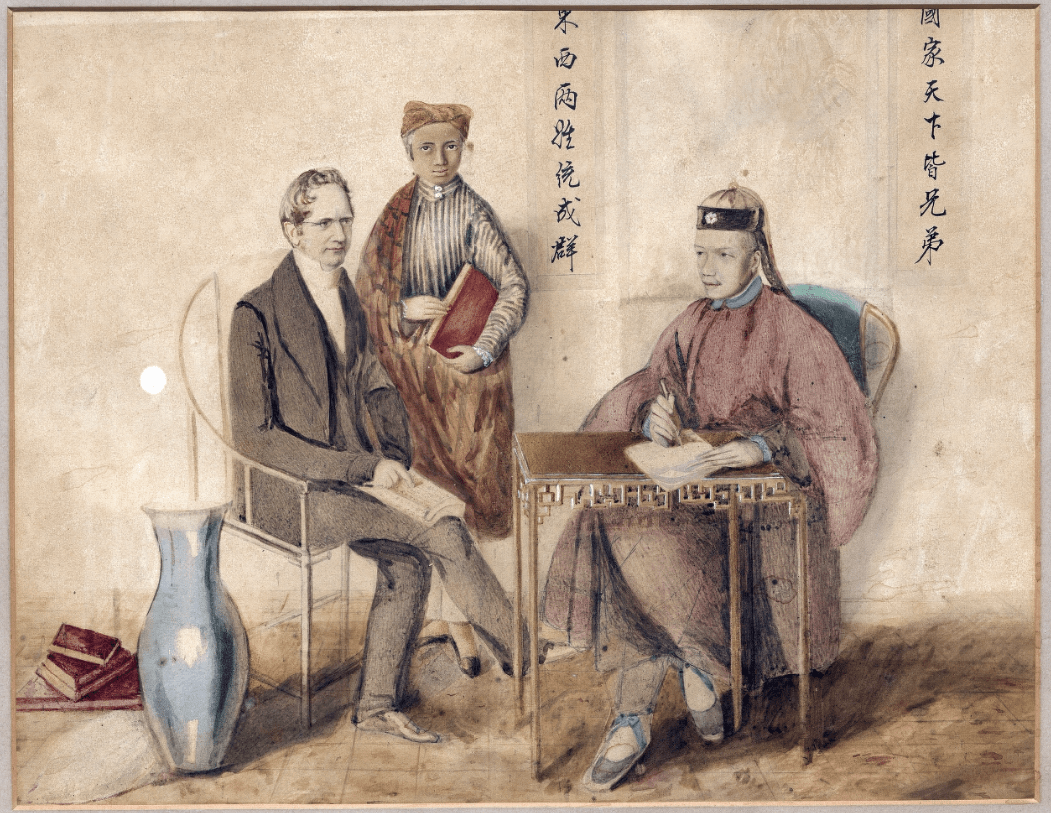

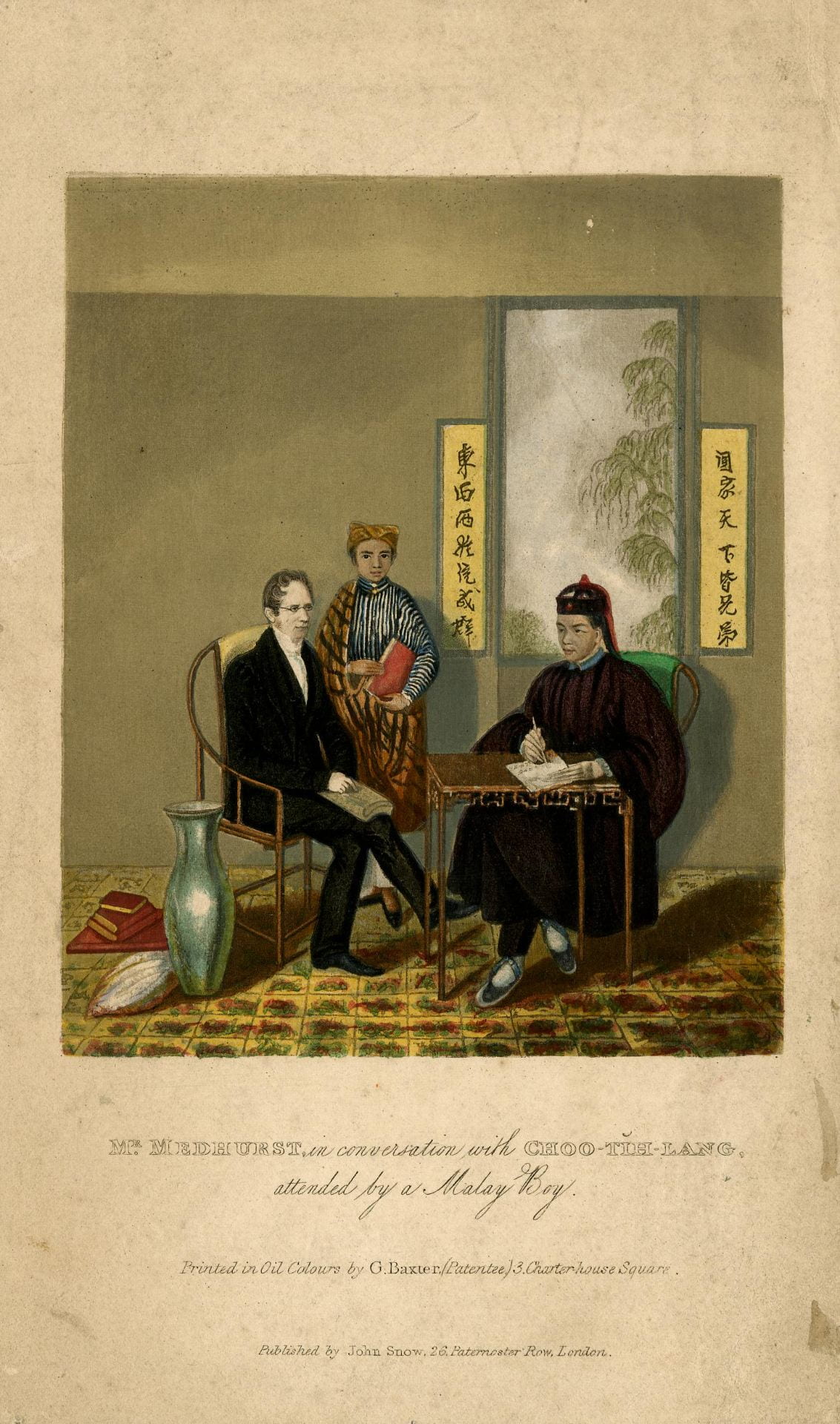

Finding that little was known about the country, Medhurst completed this undertaking by writing China: Its State and Prospects, a lengthy treatise summarising its history and culture, his journeys and efforts to date and what needed to be done to make progress.[4] The well-known frontispiece comprises a coloured engraving, based on an oil painting done by the artist and printer, George Baxter (1804-1867). Commissioned by Jemima Luke, as a gift for her father, Thomas Thompson, a wealthy philanthropist and prominent member of the LMS, the painting was later presented to the Society and retained in its Collection.

Fig. 2. Watercolour by George Baxter of ‘Rev. W. H. Medhurst D. D. China, with Pundit and a Malay Boy’. Archives and Special Collections, SOAS ref: CWM/LMS/Home/China Pictures/12 (CWM/LMS/01/09/05/08/12).

Fig. 3. Frontispiece to China: Its State and Prospects, by Walter H. Medhurst © The Trustees of the British Museum

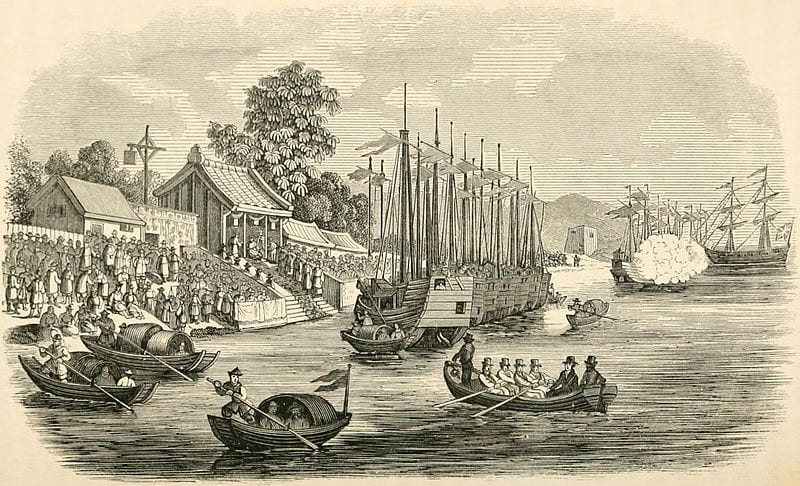

Medhurst is here depicted as the Western sage dictating to his Chinese assistant, Chooh-Tih-Lang (Chu Tak-leung), against an oriental background. Once again elegantly attired, but lean and scholarly, he comes across as intensely serious and, without any religious frills, the sort of man to whom non-conformists ought to be happy to entrust their subscriptions. Inside the book, along with a number of illustrations depicting the ‘heathen’ practices of the Chinese, is a picture of Medhurst and his fellow missionary, Edwin Stevens, being rowed ashore at Woosung (Wusong). Complete with top hats, they are projected as emblems of western civilisation. The image has been through an interesting process of transmission and multi-national composition. The Chinese characters in the couplet in Figure 2 were clearly the work of a Chinese writer, whereas those in Figure 3 are crude approximations, made by a foreign copyist, with the strokes bent out of shape.[5]

Fig. 4. Landing at Woosung. From China: Its State and Prospects, plate opposite p. 446.

How much the missionaries impliedly validated Britain’s unwelcome entry into China, following the conclusion of the First Opium War in 1842, is a moot point but, once achieved, Medhurst lost no time in opening a mission station in the newly-established treaty port of Shanghai. Arriving in December 1843, he would spend the next twelve years there, building a congregation, a hospital, with his medical colleague, Dr William Lockhart, and establishing a thriving press, which published both secular and religious works, including a new translation of the Bible into Chinese, the Delegates’ Version, which Medhurst had co-ordinated. With ferocious energy, he preached and travelled, making one lengthy trip in Chinese disguise, for which he was heavily criticised, as it grossly violated the permitted limit of one day’s journey, and, narrowly avoiding severe injury when he and two colleagues were set upon during another expedition – experiences, which he recorded in detail, both in published works and in his reports to the LMS in London.[6]

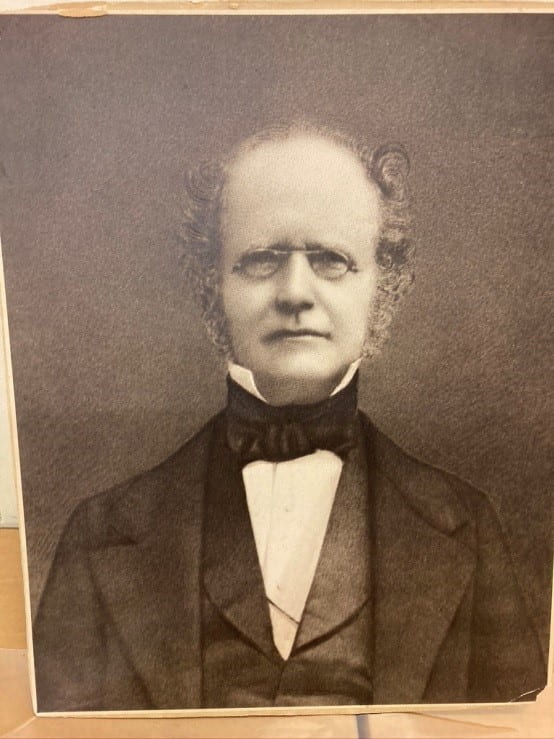

Unable to visit England, Medhurst saw the importance of maintaining contact, not just through the written word, but through images. When his daughter, Martha, was setting off from Shanghai with her husband, Powell Saul, he entrusted her with a portrait of himself to be presented to the LMS. As he informed the Directors, it had been ‘taken by a Chinese artist [and] is said to be a good likeness though roughly finished’.[7] Although we cannot be sure, it most probably formed the basis for the engraving made by John Cochran (1803-1865) for the front page of the Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for 1852. Again, it depicts him as intensely serious and dispels any notion that he might be simply a Bible-thumping eccentric in danger of ‘going native’.

Fig. 5. Revd. W. H. Medhurst D. D. From ‘Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle’, 1852. Archives & Special Collections, SOAS ref: CWM/LMS/Home/Missionary Portraits/Box 4 (CWM/LMS/01/09/02/01/346).

In letters to her sister, Martha, Medhurst’s daughter, Eliza Hillier refers to a number of ‘likenesses’ of her parents, telling her, on one occasion, not to ‘send them to Canton to be copied for me as I only wished for a daguerreotype copy and do not care for a Chinese one’.[8] Sadly, none of the ‘likenesses’ of her mother, Betty Medhurst or copies made in Canton (Guangzhou), have survived and we have only a much later photograph of her.

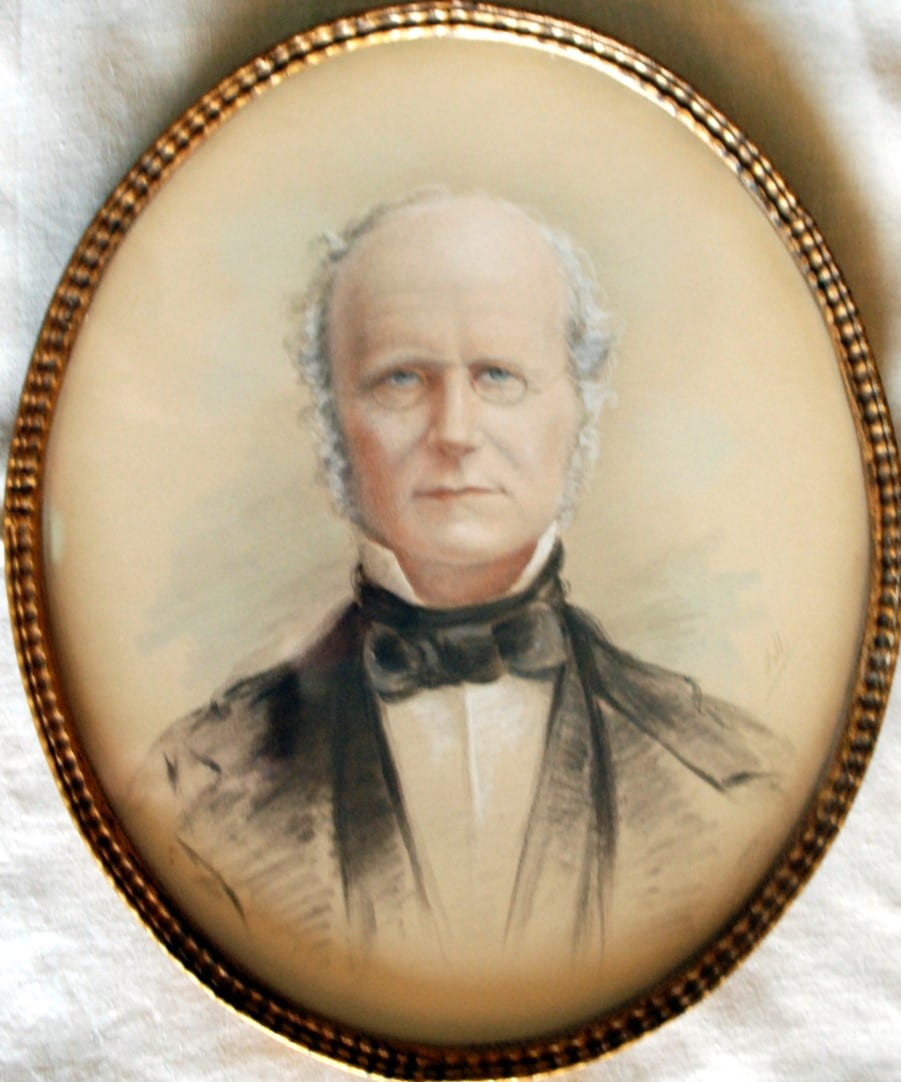

However, there is a fine pastel portrait of Walter Medhurst, undated and unattributed, which has remained in the family. Most probably this is an artwork copy of a portrait photograph of Medhurst by Robert Sillar. It is more flattering than the photograph, more of an idealised or optimised portrait, ‘air-brushing’ out the, perhaps unwelcome, ‘warts and all’ nature’ of the photograph. Following his death, cartes de visite were made of the pastel portrait, by a Fleet Street studio, T. N. Fall, and circulated amongst family and friends.

Fig. 6. Pastel portrait of Walter Medhurst, by an unknown artist. Undated. Hillier collection.

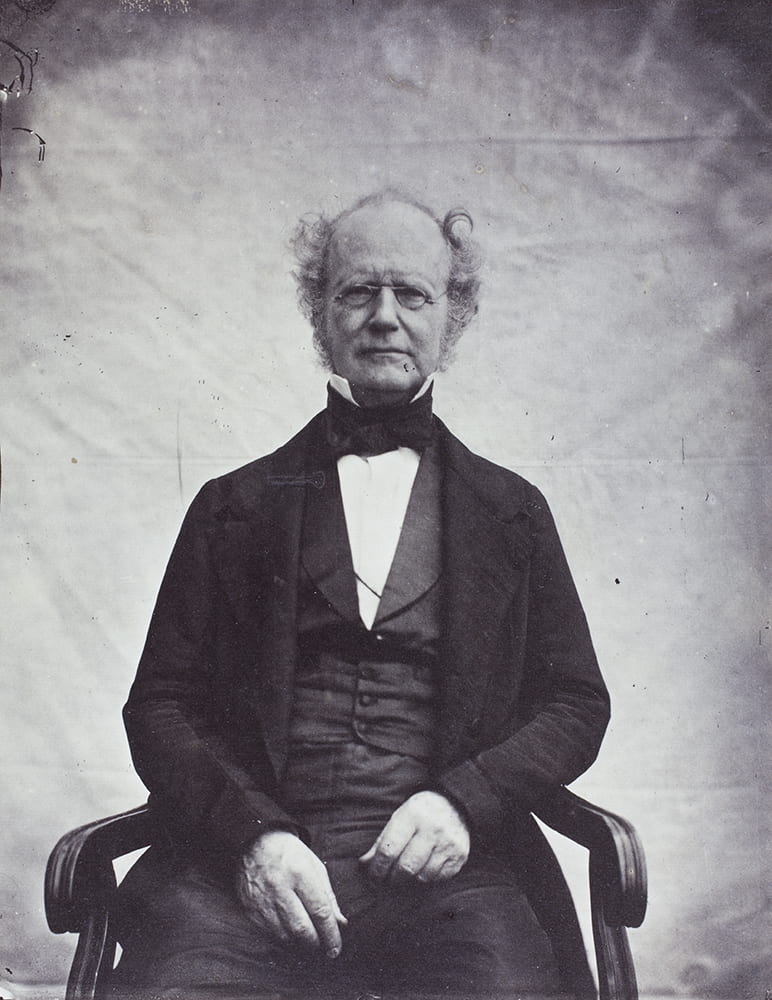

By 1856, Medhurst, along with Dr Lockhart, was by far the longest-serving resident in Shanghai and one of its most well-known figures, not only as a missionary and Sinologue, but also as a founding member of the Shanghai Municipal Council. Not surprisingly, therefore, when the accomplished amateur photographer, Robert Sillar arrived in Shanghai, he asked Medhurst to sit for his portrait, shortly before Medhurst left for England.

Fig. 7. The Revd. Dr Walter Henry Medhurst, Shanghai, 1856. Photograph by Robert Sillar. Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution reference: L04357-003c. HPC ref: VH02-007.

Taken exactly forty years after the first portrait was done, the result is an outstanding picture, conveying all the gravitas of his years, but also the elegance to which Medhurst obviously still attached importance. It is not known how many prints of Sillar’s photograph have survived, other than the one in an album held at the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution.

A final twist to the story is that an enlarged but half-length, photomechanical print based on Sillar’s photograph, was made by the London photographer, Reginald Haines (1872-1942), seemingly at the request of the LMS, since it forms part of the Society’s collection.[9] This portrait is also flattering, presenting a seemingly younger man without wrinkles. When and why it was made in this way is not clear, but it may have been done when the Mission Museum closed in 1910 and the portrait archive was being re-organised. This means that there are now three known versions of the same image and it is just possible that a fourth one may still be found.

Fig. 8. Photomechanical print by Reginald Haines, undated, based on Sillar’s photograph. Archives & Special Collections, SOAS ref: CWM/LMS/Home/Oversize Portraits/8 (CWM/LMS/01/09/03/08).

Medhurst and his wife left Shanghai in September 1856 and, sailing via the Cape, they arrived in England in January 1857. But the years in the East had taken their toll and he died just a few days later on 24 January. He was buried in Abney Park Cemetery, London. In some ways, Medhurst was ahead of his times, understanding the importance of promoting the missionary cause, both in England and in China, through the use of images that would convey the seriousness of the message and, plainly, he took care when deciding how he should be portrayed. The four examples held by the LMS show how such pictures enabled contact to be maintained with outlying missionary stations and how, even after his death, they were treated as an important part of the LMS archive, powerfully evoking his and his colleagues’ early endeavours in the Ultra-Ganges Mission.

[1] I am very grateful to Joanne Ichimura, Archivist, at Special Collections, SOAS, London, for all her assistance and to Special Collections for permission to reproduce the images in this post.

[2] The picture was one of 165 miniatures dating from around 1798 to 1844, primarily watercolour on ivory, with a small number being pencil on paper with some silhouettes and drawings, showing missionaries appointed to the London Missionary Society. A guide book, ‘London as it is to-day’(1851), refers to a number of portraits being exhibited in the London Missionary Museum, Blomfield Street, Finsbury, which had first opened in 1814 and which, with its large ethnographic collection of ‘idolatrous objects’, had become a popular attraction by the 1840s; see the Illustrated London News, 25 May 1843, p.342, and https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/archives/2017/07/03/miniature-portraits-in-the-london-missionary-society-archive/

[3] See Andrew Hillier, Mediating Empire: An English Family in China: 1817- 1927 (Folkestone: Renaissance Books, 2020), p.7 and for other aspects of his life referred to in this post, pp. 3-53.

[4] W.H. Medhurst, China: Its State and Prospects, with Especial Reference to the Spread of the Gospel (London: John Snow, 1838).

[5] The picture is an almost exact copy of one by William Alexander, entitled ‘Temporary Buildings at Tientsin’; see The Costumes of China (London: William Miller, 1805), plate 44. I am grateful to Jenny Huangfu Day for drawing this to my attention.

[6] W.H. Medhurst, A Glance at the Interior of China Obtained During a Journey through the Silk and Green Tea Districts, taken in 1845 (Shanghai: Mission Press, 1849 and London: John Snow, 1850), reprinted in part in Elizabeth H. Chang (ed.), British Travel Writing from China, 1798–1901, Vol. 2, Mid-Century Explorations, 1843–1863 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2010), pp. 51–146.

[7] Letter, Medhurst to Directors, LMS, 13 February 1851, SOAS, CWM/Central China/1843–1854.

[8] Letter, Eliza Hillier to Martha Saul, 31 March 1853, Andrew Hillier, My Dearest Martha: The Life and Letters of Eliza Hillier (Hong Kong: City University Hong Kong Press, forthcoming March 2021)

[9] Haines was a fashionable portrait photographer with a studio in Southampton Row; see https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp104543/reginald-haines.