Anne Gerritsen is the author of The City of Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and the Early Modern World (Cambridge University Press, 2020). She teaches Chinese history and global history at the University of Warwick and serves as the director of the Global History and Culture Centre. She also holds the Chair in Asian Art at the University of Leiden.

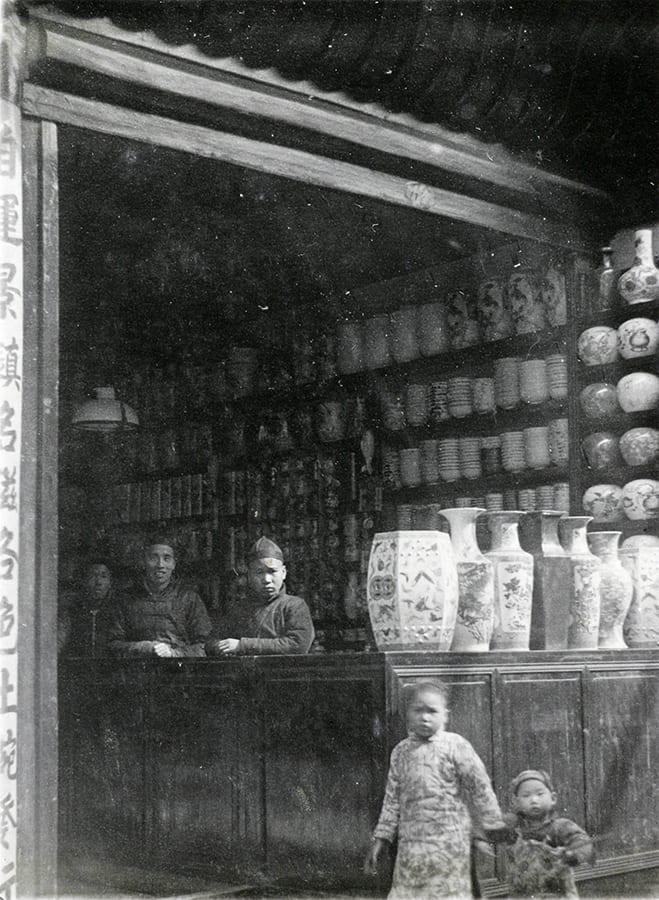

Fig 1. Porcelain stall at a market, Beijing, c.1905. SOAS archive catalogue ref: MS 381142. HPC ref: Ru02-18.

China means many things. In the English language, the word refers both to the country and to the material that was exclusively produced there until the early eighteenth century. To some, references to ‘ceramics’ probably only conjure up images of road-side craft shops or of glass-fronted cupboards in museums, antique shops or grandparental homes. Pottery, stoneware, ‘china’, and porcelain all might have a similar set of associations. Instead of dwelling on those, I’d like to connect porcelain instead to words like dust, labour, life and death. Of course, in imperial China, beautiful porcelains were made for emperors and élites and decorated imperial palaces and temples, as well as Custom Houses, as the collection testifies. But the industry where such fine pieces were made was above all a business where people got their hands dirty. It also employed thousands of labourers, whose life and death depended both on the orders for large quantities of porcelain from the imperial court as well as the world beyond China.

Fig 2. Ceramics worker moving saggars. Photograph by Anne Gerritsen.

Filthy work

Ceramics are made from soil and water. There is a bit more to it, of course: to make good ceramics, you need clay, and to make excellent ceramics you need clay that turns into an attractive colour when it has been fired in a kiln (or else you have to cover the ceramics first with an underlayer of glaze so that the unattractive colour doesn’t show), and to make really fine ceramics that can withstand firing at a high temperature so it becomes a hard piece of porcelain, you need a kind of clay that has been kaolinized over the many centuries that the clay was under the soil, or a combination of porcelain clay mixed with pure kaolin. But basically, ceramics are made from clay and water, and when the clay dries, it turns to dust. Where ceramics are made, there is dust everywhere. One fourteenth-century official, stationed in the county seat near the biggest porcelain manufacturing centre in imperial China, Jingdezhen 景德鎮, was so disappointed to be stationed in this place that he wrote:

‘Alas, I have to remain here for three years. How come I do not have a heart of iron? Just staying here my hair will go grey early.’[1]

Fig 3. Workstation in a porcelain manufactory. Photograph by Anne Gerritsen.

Not just dust makes it an unattractive place to work, but also the smoke rising up from the chimneys: before electric ovens, the kilns for firing ceramics had to be brought up to temperatures of over a 1000°C by feeding it with wood (mostly in the south) or coal (mostly in the north), and then maintained at that temperature by maintaining it for days on end. Workers would feed the fires through the night, looking through small holes to judge the temperature by eye. The average quantity required to fire one of the big kilns in Jingdezhen in the early sixteenth century was around 9,000 kg of firewood, which all had to be floated down the river from the hillsides surrounding the town.

Fig 4. Man adding wood to a kiln next to a wall with an inscription at a tile and brick factory near Mentougou Qu, c.1933-46. Photograph by Hedda Morrison. HPC ref: Hv24-070.

Labour

A lot of labour was involved: all this wood had to be transported, dried, chopped, stored and lifted into the kilns. The clays, too, had to be dug at sites scattered in the surroundings of Jingdezhen, transported, pulverized, purified, dried, mixed, kneaded, shaped, and so on. Individual pieces of porcelain were not made from start to finish by a single potter; the whole process was segregated into separate tasks, with some doing labouring tasks like chopping wood or mixing clays, and others doing more skilled tasks like preparing pigments or painting flower patterns. It was precisely because of this division of labour that the production could be scaled up, to produce thousands of pieces of porcelain in a single firing and many millions of pieces over the centuries that Jingdezhen was the only place in the world that could produce such vast quantities of such fine pieces.

Skill

Workers came from the surrounding counties in Jiangxi and neighbouring provinces and performed mostly unskilled labour. Skilled hands were more difficult to find and even more difficult to keep; the imperial kilns desperately needed them to help fulfil the demands from the court, but private kilns offered easier work and more reward. Probably, it was precisely the ecosystem in which private and imperial kilns shared talent and resources that explains Jingdezhen’s long-term success.

Fig 5. Rice bowls at a pottery, Fujian province, c.1900-1910. Cadbury Research Library archive finding number: DA26/2/2/2 (John Preston Maxwell Papers). HPC ref: Mx03-099.

Life …

So, rather than thinking of porcelain only in the context of display, I think we should pay more attention to the ways in which porcelains were part of daily life. Kilns were scattered across the landscape throughout China, and ceramics were made everywhere, but some production sites were famous for a specific type, or ware: so, Jingdezhen was famous for its blue and whites; Yixing for its red teapots; Cizhou for its pillows, and so on. Such regional specialisation also meant the trade and transport of ceramics, and the selling of ceramics in dedicated shops.

Porcelains came in all shapes and sizes, and the production could as easily be adapted to the demands for one-off pieces from emperors as to the requests for unusual shapes that came from overseas, like the butter dishes and gin bottles for the Dutch market. But the vast majority of what was produced were bowls. Shaped to fit inside the space of a hand, wide at the top to accommodate heaped rice or cool hot soup, narrow at the base to give elegance and facilitate stacking, bowls accompanied people through life.

… and death

The picture below, of an execution site in Canton, confirms that ceramics were also part of death. The notes accompanying the images explain: ‘At an otherwise innocuous pottery factory, a wooden cross leans against the wall on the right. This cross was apparently used for torture and execution by crucifixion. Called Ma-tow, this place was an execution ground for Chinese felons only.’[2] The pots standing around form merely the background to this site of executions, their presence nothing more than a feature of this space, an obstacle to clamber across to get a good look at the implements of death.

Fig 8. Place for capital punishment, Guangzhou. SOAS archive catalogue ref: MS 381233. HPC ref: HR01-086.

But pots also provided the space inhabited by the remains of human life, their final resting place in the landscape. So, rather than thinking of ceramics only in their final use-phase, gleaming behind glass in a shop or museum, we should also consider the dust and the labour that went into making them, the joys they gave when handling them, and the sorrows conjured up by funerary urns. As the many photographs in the collection that feature porcelains show: pots were part of life, labour and the loss of life.

Fig 9. Funerary urns (金塔), New Territories (新界), Hong Kong. From an album in The National Archives referenced as: ‘HONG KONG 9. Work of the Chinese and British Boundary Commissioners delimiting the New Territories, 1898 (CO 1069/452)’. HPC ref: NA22-28.

[1] Hong Yanzu, ‘Observations one autumn morning in Fuliang’ 浮梁秋曉書事三首, Xing ting zhai gao, 12a. I discuss the writings of Hong in ‘Fragments of a Global Past: Ceramics Manufacture in Song-Yuan-Ming Jingdezhen’. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 52.1 (2009): 117-152.

[2] Notes added to HR01-086, in the Ruxton Family Collection, Historical Photographs of China.