Drawing on his own records and images from the Historical Photographs of China platform, Dr Andrew Hillier, author of Mediating Empire: An English family in China 1817-1927 (2020) has posted a number of blogs here and elsewhere about his family. In this post he provides an account from other family records of a phase of the history of the foreign communities in treaty port China of which we have only a few photographic records: the years of Allied civilian internment during the Pacific War.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, Ella Hillier, whose husband, former Hongkong & Shanghai Bank Peking Manager Guy Hillier, had died in 1924, was in Tsingtao (Qingdao). She would go on to spend almost three years as an internee, and whilst the story of these years is well-known, her account, which is summarised in this post, shows how life, in such circumstances, can be banal, farcical and frightening but also, on occasions, uplifting.[1]

1. Ella Hillier. Image courtesy of Jennifer Peles and Fiona Dunlop.

Following the death of her husband (on whom see A Banker and his Amanuensis), Ella Hillier spent her time travelling and looking after her four nephews and nieces, who were at school in England. In 1940, now in her early sixties, she returned to China and stayed with her sister, Mary Celia Napier, in Qingdao, the cosmopolitan port-city and former German colony on the Southeast coast of Shandong province.

2. Butterfield & Swire’s office, Qingdao, 1938. The building had been completed in 1936 and was sometimes incorrectly referred to as the Chartered Bank building as the bank leased the ground floor for a branch office. It was located in what was the southern end of the general business district. HPC ref: Sw08-142.

In May 1941, Mary Celia left to join her family in Shanghai and Ella stayed to look after the house. By this time, Shandong was under Japanese military control, but, within limits, the British and nationals of other neutral powers were able to carry on their lives as before.[2] With the outbreak of the Pacific War on 7 December 1941, this abruptly ended.

3. The house belonging to Norman and Mary Celia Napier in Qingdao, c.1938. Image courtesy of Jennifer Peles and Fiona Dunlop.

For the first ten months, Ella was confined to her house, but was allowed to go out for shopping and exercise from noon until three p.m. each day. In July, 1942, she was joined by a Mr and Mrs X (as she calls them) and ‘life became less nerve-wracking’. In October, Mrs X was taken to the German hospital and two days later Ella and Mr X were collected by lorry and taken to the Iltis Hydro Hotel at Iltis Huk, a seaside suburb of Qingdao.

To their consternation, they were told they would be sharing a room. ‘“But this is not my wife!”, said Mr X. “You must put this lady elsewhere!” The officer drew a hissing breath. “So, she is not your wife? Then she must join the loose ladies – the ah – unattached – women in the Dance Hall.”’ And so, Ella bedded down in the Trocadero Dance Hall, which, from then on, became known as ‘The Dormitory for Loose Ladies’ and its inmates as the ‘Trocadero Dance Girls.’

The 27 ‘loose ladies’ comprised a mixture of nuns, missionary nurses, teachers, typists, and ‘at least three genuine loose women, very much divorced from their husbands.’ With a total of 147 internees in a space designed for 45 guests, life was far from comfortable. However, a routine was quickly developed, tasks were assigned and Ella was put in charge of the library. A caterer was instructed to provide meals, ‘with two Chinese cooks in the kitchen being supervised by ladies who took turns week by week. Volunteer young men and girls waited at table, a week at a time, and helped to wash up.’ Without any sort of heating, it became painfully cold as winter set in. Eventually, they were able to obtain some stoves and these provided some minimal heat.

Our most wonderful memory was the festival on Christmas Eve. After breakfast, strong men cleared the Trocadero of all the beds… a large Christmas tree was put up and decorated with tinsel ornaments and silver rain. Carols and Christmas glees were sung in the afternoon, followed by a Nativity Play. At the end Father Christmas appeared and distributed toys for the children, including 3 beautiful bride-dolls, dressed by our Dutch friend. It was a happy radiant time for all. On Christmas morning we held services and opened the gifts sent to us by neutral friends outside.

Whilst ‘a beast’ of a commander then took over, and some internees were subjected to brutal and humiliating treatment, in the main, life was manageable.

In March, 1943, having been told that they were being transferred to a former American Presbyterian College, situated just outside Weihsien (Weifang), they were ‘the first to burst into that silent camp, empty and unfinished, to prepare for all the rest’. Eventually, the Civil Assembly Centre would house some 1,800 internees, including 500 priests and nuns, many from Mongolia.

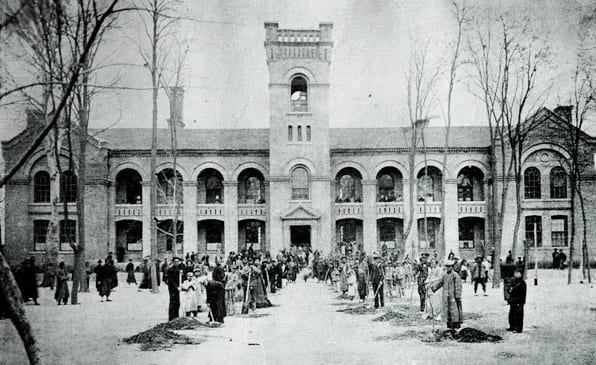

4. Aerial view of Weihsien Civilian Assembly Centre (internment camp), previously the American Presbyterian College compound, Weifang.

The Camp Commandant, who had been the former Japanese Consul-General in Honolulu, was ‘quite good-natured, allowing the internees to administer the internal affairs of the Camp’. The rows of students’ rooms were given over to married couples, while the class-rooms were transformed into dormitories for single men and women. Internees from the north were allowed unlimited quantities of baggage and two grand pianos arrived. ‘There was’, she reported, ‘a Salvation army brass band from Peking, a Hawaiian jazz band from Tientsin and a camp orchestra of 26 instruments, including a beautiful American nun playing the saxophone’. There was also a sixty strong Choral Society, which sang choruses from The Messiah, Elijah, Hiawatha and St. Paul and presented various glees and madrigals. A Labour Bureau operated at first, finding camp jobs for everyone.

We were a miniature world, having merchants, engineers, bank clerks, architects, professors, typists, dressmakers, nurses , doctors, manicurists, barbers, bar-tenders, shop keepers, prostitutes, an Olympic champion runner [Eric Liddell, whom the children called ‘Jesus in running shoes’] a Rhodes scholar, as well as two Basque pelote players who had come to China from Cuba.

A bakery was started by two Armenian bakers, with men working shifts under them, so there was good bread but otherwise food was scanty, save when parcels were sent by neutral friends. Carpenters began making necessary tables and benches, and stools for the water-closets which the Japanese had erected in their style – holes in the floor.

5. Planting an avenue of trees leading to the main building and bell tower, American Presbyterian College, Weifang. Later the compound became the Weihsien Civilian Assembly Centre (internment camp).

The Church was renamed the Assembly Hall, and was used during the week for lectures, plays and concerts and classes. Four schools functioned: the Peking American School, the Tientsin Grammar-School, the Chefoo School (‘some 250 pupils with excellent teachers and apparatus’) and a Catholic School. Once again, Ella was appointed Head of the Library, which, amongst the 3000 titles, included some 500 books for children and was run by three ladies, with nine assistants.

6. Shadyside Hospital building which was a central part of the camp and now houses the museum. Photograph by Nicholas Kitto, ref DSC0593.

On Sundays the Hall functioned as a church, with early mass for the Catholics, followed by early communion for the Anglicans, then High Mass at ten, with five Catholic Bishops on the dais, followed by Matins at eleven under the Anglican Bishop Scott of North China. At 3 pm. there was Sunday School and at 4.30, Union church for non-conformists, while in the evening the Salvation Army held a song service, preceded by their band playing in the churchyard. And amongst the Catholics, there was an Australian Trappist priest from a monastery faraway in the North-West.

He considered himself absolved from his vow of silence in the Camp, and the talk bottled up in him for thirteen years gushed out in an ever-flowing stream. He gave us two lectures on the Trappist Order. He contacted all the Aussies and New Zealanders and persuaded them to celebrate Anzac Day. At night he used to buy quantities of eggs from the Chinese for the women and babies in camp, through a hole made by loosening bricks in the wall. Though he and the other priests made use of singing their prayers as a warning when Japanese guards were approaching, he was caught one night and sentenced to solitary confinement for one month, with two books of breviary. He used to chant his daily offices and prayers and hymns, and when no more came to his mind, he would start on interminable verses of “Waltzing Matilda”. His singing got on the Japanese nerves, so that they released him a week before his time.

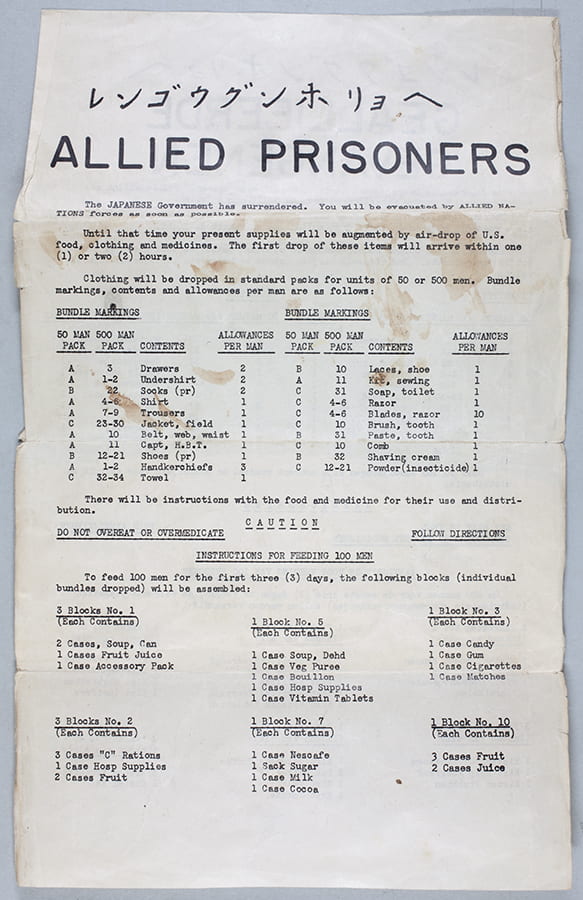

On 17 August 1945, two days after the official surrender, a rescue team parachuted from an American B24 bomber and liberated the prisoners, although many had to remain there until they could find other accommodation. For the next six weeks after that, they received food and medical supplies by parachute.

8. A leaflet picked up by Margaret Vinden, who was born in 1926, and was interned in the camp with her parents, Gilbert and Ethel Linden. HPC ref: GV-s02.

9. An American plane ‘barrel bombing’ supplies of food and clothing, Weihsien Civilian Assembly Centre, August-September 1945. Photograph retained by Margaret Vinden at the time. HPC ref: GV-s17.

Although delighted to be free, for Ella and many of the other internees, the next months were not easy. Keen to shake ‘the dust of China off [her] feet’, as she said in one of her letters, she finally left on 18 December 1945. She would not return to China but the memory of these extraordinary years would remain with her, most of all the way people had responded.

Some came with such deep resentment in their hearts that it festered like a poison, spoiling their life. Others were adaptable, making the best of things with humour, enjoying the lectures and concerts and above all the communal life.

10. The Liberation Memorial at Weihsien Civilian Assembly Centre, Weifang. The memorial was formerly unveiled in August 2005, the 60th anniversary of the camp’s liberation. The centre column has all the Chinese names of the internees, while the plaques on the surrounding circular wall list the names in English. Photograph by Nicholas Kitto, ref: Weifang 3A 1060.

Mediating Empire: An English Family in China 1817-1927 was published by Renaissance Books in April. For details, see andrewhillier.org.

—————

[1] I am extremely grateful to Jennifer Peles and Fiona Dunlop (two of Ella’s great-nieces) for allowing me access to Ella’s full account and to quote from it. I am also grateful to Nick Kitto for his advice and permission to use his images. See Trading Places a photographic journey through China’s former Treaty Ports. Two of Nick’s great-great uncles and their wives were interned with Ella. The subject is comprehensively described in Greg Leck, Captives of Empire: The Japanese Internment of Allied Civilians in China, 1941- 1945 (Bangor, Pa: Shandy Press, 2006); see also Captives of Empire. The new China Families platform contains extensive lists of Allied internees across China and Hong Kong, and also neutral foreign residents in occupied Shanghai.

[2] For an account of life in Qingdao immediately before the outbreak of war, see Forgiven but not Forgotten, Memoirs of a Teenage Girl Prisoner of the Japanese in China by Joyce Bradbury.