Nicholas Kitto describes the project which culminated in the recent publication of his book ‘Trading Places, A Photographic Journey Through China’s Former Treaty Ports’ (Blacksmith Books)

It was quite late on 16 December 1996, and I was walking along Racecourse Road in Tianjin. We had just finished a fine dinner hosted by my client’s local office and as this had included traditional rounds of maotai, the cold night air was very welcome. We had driven along the road earlier in daylight when returning from the client’s facility in the Tianjin Economic Development Area and had spotted a house that may have been the one I sought. As we were leaving for Shanghai the next morning this was the only opportunity I would have until a subsequent visit.

As a professional accountant based in Hong Kong, from the mid-1990s I began to travel frequently to the mainland on business. Two weeks before my 1996 visit to Tianjin, I was with my father on the Isle of Man and mentioned my forthcoming trip to the city where he was born and had lived until aged six, when the family moved to Hankou (my grandfather, Jack Kitto, was with the Asiatic Petroleum Company (North China) Limited, one of two subsidiaries of the Royal Dutch Shell group operating in China at the time). ‘Wouldn’t it be a laugh if you found our old house’, he challenged before drawing a rough sketch of the building and a map of its location, despite the years which had passed and his age when he had last been there.

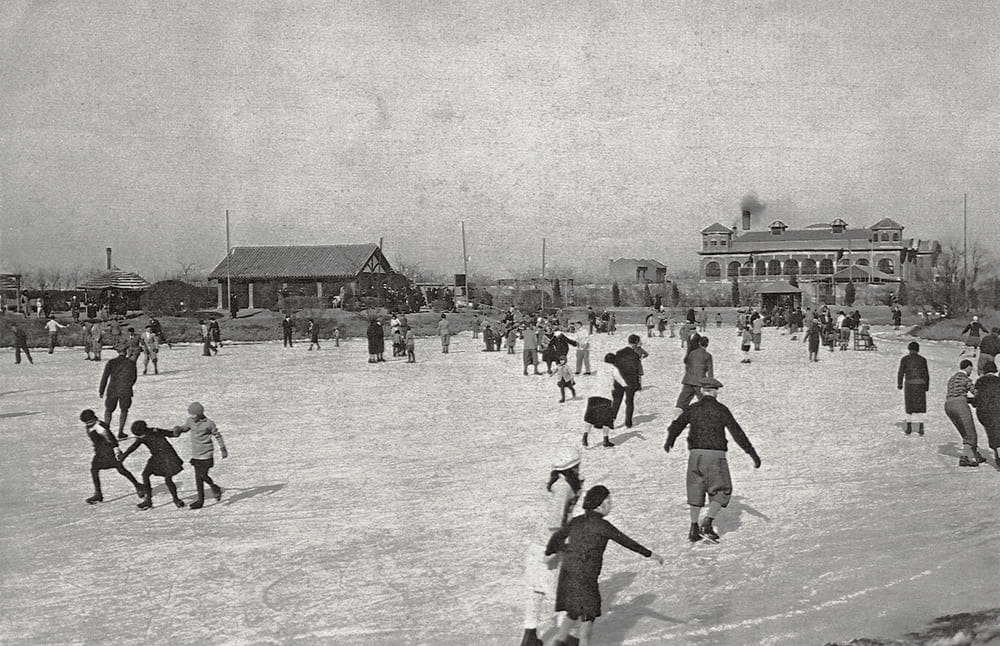

Ice-skating on the Tientsin Country Club’s small lake in around 1930. My father is somewhere amongst those on the ice.

Thanks to my father’s drawings, once I was on foot that chilly evening it wasn’t too difficult to identify the house due to certain unique features and it being on an apex of a bend in Racecourse Road at a point where two other roads joined in a ‘V’ shape. The next morning I was up early to take some photographs and my father soon confirmed that we had succeeded.

The following year in December 1997, armed with a photograph from around 1930 provided by my father as second challenge, I was able to locate the former Tientsin Country Club. My father remembered the Club well, at least from the outside, as children were seldom permitted inside. This time I had the hotel driver’s local knowledge to thank for the find.

Nick Kitto outside the Tientsin Country Club, immediately after locating it in December 1997.

The Tientsin Country Club, now known as the TY Club, soon after a full restoration was completed in 2014. The Club includes a heated indoor swimming pool, a squash court, a bowling alley, a small theatre, a sports bar and extensive dining facilities, largely all as in the original lay-out. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

In the years that followed I continued to visit Tianjin occasionally (memorably attending a ‘tea dance’ in the Tientsin Country Club one Friday afternoon in January 2002) but my interest in the buildings was largely limited to those with connections to my family, although at that time I had little idea of the extent of their activities in China. While visiting Tianjin with my father in November 2004, this began to change. On this occasion, apart from having a drink in the old family house, now conveniently a bar, and also a guided tour of the Tianjin Country Club by a kind and understanding caretaker, we walked around the old city centre and it was hard not to notice the large number of western-style buildings. I wanted to know more about these buildings: who used them and for what purpose, how many of them remained in China and in which cities were they to be found? And so I began to read about the treaty port era and was soon fascinated, especially as it was obvious that, even from my limited experience in Tianjin and Shanghai, a great number of buildings from those days had survived.

The Astor Hotel in Tianjin. In 2010 a restoration of the hotel was completed. The old brick walls, wooden trimmings, fittings, floors and doors were preserved down to the smallest detail; the result is magnificent. The main bar in the hotel is appropriately named after William O’Hara, the last owner of the Astor (from 1903 to 1949). Released from Japanese internment, he re-established the hotel after extensive renovations. But the municipal authorities confiscated the hotel in lieu of back-taxes and O’Hara left for New Zealand in 1949, heart-broken and virtually penniless. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

Butterfield and Swire premises, Victoria Road, Tianjin, 1919. Photograph by G. Warren Swire. HPC ref: Sw04-112.

A great-great-uncle of mine, Lionel Howell, worked at the Butterfield & Swire’s shipping office in Tianjin, amongst other locations, and was present during the Boxer troubles. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

Happily, a long-time friend, Robert Nield (1), shared my interest and, after a tentative visit to Tianjin in November 2007, in September 2008 our exploration of China’s former treaty ports commenced in earnest. Robert’s objective was to write on the subject; mine to photograph as many of the surviving buildings as we could find. During our travels we certainly found a large number of these buildings; indeed there was no city we visited where we didn’t discover something.

The Custom House in Guangzhou was built in 1914 to replace its predecessor which was destroyed by a fire in 1912. This image was chosen as the cover of the book and is a particularly good example of the painstaking efforts that were made during a restoration process. This image dates back a few years and the building has inevitably weathered somewhat since. Nevertheless the finely restored detail remains visible today. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

We were fortunate with our timing. With the approaching Beijing Olympics of 2008 many cities had invested significant resources in restoring buildings of historical interest (not only from the treaty port era of course), and restoring them to a very high standard. This activity was not limited to the Olympic host cities as restoration projects extended throughout the country from Harbin in the north, to Beihai (Pakhoi) and beyond in the south.

The British consulate in Beihai was constructed in 1885 to replace the first consulate established in 1877, which was little more than a fisherman’s shack balanced precariously on stilts over the water’s edge. In 1999, the building was moved 55.8 metres to make-way for a dual carriageway. It now stands at the entrance to the Beihai No.1 Middle School. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

The French Custom House in Mengzi, deep in Yunnan province, was built in expectation of increased trade with what is now Vietnam. In order to encourage this trade the French built a railway linking Haiphong on the Vietnamese coast with the provincial capital at Kunming. The construction of the railway was a massive undertaking through difficult mountainous terrain and involved more than 100 viaducts and 150 tunnels. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

Often extraordinary effort was made to save a building or restore a whole area close to how it looked in the 1930s. This included, but was not limited to, moving structures several metres to make way for new development, diverting traffic underground and demolishing gruesome concrete bridges from the 1950s. Demolition to make way for the new might have been a more popular option and it is impressive, and certainly fortunate, that this was not adopted in so many cases. And the restorations continue to this day. At the time of writing, the city of Yantai (previously known as Chefoo) is undertaking a large project to restore the former foreign settlement area to its previous state. Although much has already been completed, work will be ongoing for some years yet.

The German Consulate in Hankou. The front door, which faces the Yangtze River, leads up to the consul’s apartment while the offices on the ground floor were accessed from the rear. The building is now part of a large Wuhan Municipal Government compound. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

The Custom House at Wuhu was completed in 1919 and replaced an 1877 version that was less accessible having been built further inland along a creek. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

Our planning for each visit followed a similar pattern. Robert had by far the greater knowledge and resources, especially when it came to maps, but I would always undertake my own research, with a particular emphasis on buildings which may have survived. A day or two before a visit we would ‘fly-over’ the city on Google Earth, comparing interesting-looking roofs to old maps. From this Robert would produce extensive copies of maps and we would plan a route, with me keeping an eye on the position of the sun for the benefit of my camera.

The Shanghai Bund looks spectacular since its restoration was completed in 2012. Buildings from Butterfield & Swire in the French Concession to the British consular compound at the far end were restored. Much of the motor traffic has been diverted underground and the ten-lane road reduced to four. The resulting space was pedestrianised, creating a broad walkway running the full length of the Bund by the river. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

Once on site, we would leave our hotel after an early breakfast and explore on foot, that being the only way to ensure we did not miss anything. Each day was long with no break for lunch, but we would try to be back at our hotel by 6pm. Often we would cover more than one city in a single visit. Generally we booked a hotel car and driver for a day trip to another city but sometimes the distances were too far, in which case we would go by train and stay for a few days.

Gardeners at ‘Hazelwood’, Shanghai. Photograph by G. Warren Swire, taken soon after completion of the building in 1934. HPC ref: Sw08-019.

The Butterfield & Swire taipan’s residence, ‘Hazelwood’, designed by Clough Williams-Ellis. The building is now an annex to an international hotel, the main building of which is visible to the rear. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

We frequently created considerable curiosity but this was always friendly and, in particular, I never had any trouble with my large camera and lenses. Sometimes our driver would become interested in our activities, especially if we had hired him for more than one day. I remember one appearing on the second day with his own pocket camera and he enthusiastically joined-in the hunt. On another occasion we were investigating the recently redecorated former Butterfield & Swire agent’s residence in Qingdao when the architect arrived with more than a concerned look at our intrusion. As it happened, we had copies of G. Warren Swire’s earlier photographs of the building which we offered to the architect. He was delighted, but insisted on returning them after he had made a copy. We had many such experiences and these all helped to make every visit fruitful and thoroughly enjoyable.

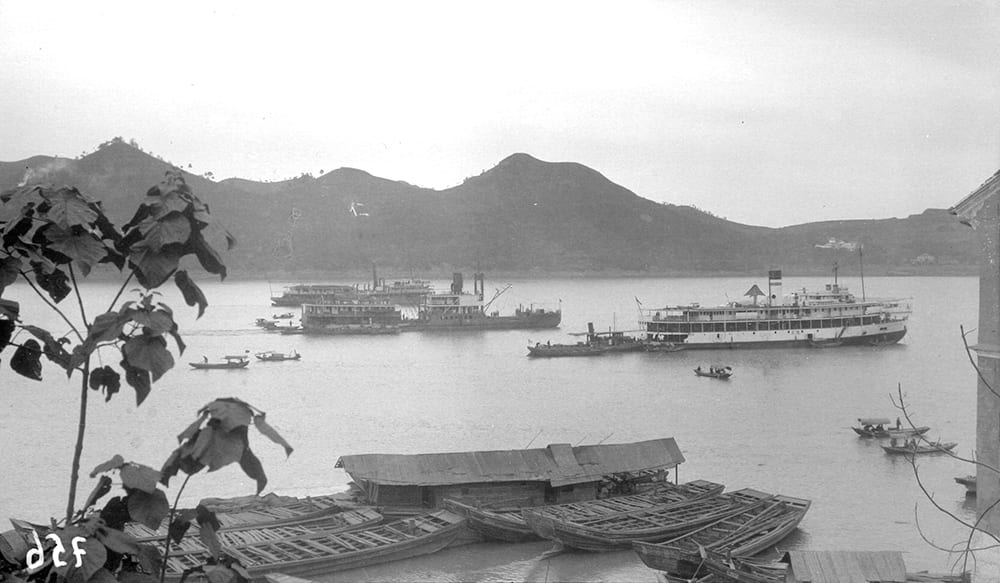

River traffic on the Yangtze River at Yichang, including ‘Lung Mow’, ‘Wanhsien’ and ‘Shasi’, c.1923-1924. Photograph by G. Warren Swire. HPC ref: Sw06-094.

The Yangtze River at Yichang, taken slightly further downriver from Warren Swire’s, but the consistent shape of the hills is clear. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

By 2016, having made over fifty visits to as many former treaty ports and settlements, I had accumulated over 4,000 photographs of buildings (2) and it seemed timely to produce a book to showcase them and to assist those interested in locating them. That took time as I had writing to be completed and photographs to be chosen, but the book was at last published at the end of March this year and a few of the more than 700 photographs it contains are reproduced here.

Hongkong and Shanghai Bank building, Dalian, c.1923-1924. Butterfield & Swire’s agent in the city rented a second-floor apartment as his residence. Photograph by G. Warren Swire. HPC ref: Sw06-129.

The HSBC building in Dalian. Photograph by Nick Kitto.

During our exploration of the treaty ports I also discovered a great deal about my family’s activities in China, but that is another story altogether.

Nicholas Kitto

Dedicated website: www.treatyports.photos

Email: njkitto@gmail.com

Two podcasts on the book: Part 1: https://mbp.ac/703 Part 2: https://mbp.ac/704

Notes:

- Robert Nield is author of ‘China’s Foreign Places, The Foreign Presence in China in the Treaty Port Era, 1840-1943’ (Hong Kong University Press, 2015). See his blog post on Visualising China: ‘Robert Nield on Wuzhou, old and new‘.

- A complete set of my treaty port images resides with the Historical Photographs of China project at the University of Bristol.