Our new blog is from Chris Courtney, Assistant Professor of Chinese History at the University of Durham. His research focusses on the city of Wuhan and its rural hinterland. He is the author of The Nature of Disaster in China: The 1931 Yangzi River Flood, a study of one of the deadliest disasters in human history. He is currently writing a history of heat in modern China, examining how ordinary people coped with the challenge of living in extreme temperatures over the course of the twentieth century.

Two centuries before the COVID-19 outbreak thrust Wuhan into the global media spotlight, the city was in the grip of another deadly pandemic. The disease described by the British as Asiatic cholera swept across the globe in seven waves in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It left millions of people dead in its wake. Imaged from the Historical Photographs of China collection offer a fascinating insight into how Wuhan experienced this disease, and how people joined the global effort to overcome it. Pandemics are not simplistic morality tales with culprits and victims. Yet they do require human agency, as people build the systems that nurture and disseminate pathogens. In this respect, cholera was, in its first flourish, a disease of empire, transported unwittingly by merchants and soldiers exploiting new transportation links. Later it became a disease of modernity, hitching a lift in the bodies of sailors, statesmen, and pilgrims as they used steamboats, railways, and automobiles to traverse vast distances at hitherto unimaginable speeds.

Much like with COVID-19, in the nineteenth century China there was considerable debate as to how and where cholera originated. Some argued that the disease had long been endemic to China, while others suggested it had been imported more recently. Much of the confusion stemmed from the fact that a new disease was given an old name. The Chinese called cholera huoluan 霍亂, which was a term that had been used for three millennia, used to describe diseases that caused a “sudden disturbance” of the bowels. Despite these pretentions of antiquity, however, cholera in its modern form seems to have only arrived in China the nineteenth century. In 1817 it spread out from the Ganges Delta, where it had long been an endemic condition, first throughout India and then to East Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Over the subsequent decades, it would reach all populated continents. It arrived in China in the 1820s, during the first pandemic wave, having most likely stowed away aboard a British merchant ship.

It is difficult to say when cholera – as opposed to huoluan – first arrived in Wuhan. It has been spreading along the Yangzi River trading route in the 1820s, and there were epidemics during the Taiping Civil War, yet the first outbreak in Wuhan to be confirmed by biomedical testing seems to have occurred in 1895, having been recorded by physicians in the Catholic Hospital. This was the same institution, today under somewhat different management, where the COVID-19 whistle-blower Li Wenliang 李文亮 worked before his tragic death. While we cannot say for certain when cholera arrived in Wuhan, we can certainly see why the city was so susceptible to the condition. It had long been a commercial centre and transportation hub, where merchants exchanged diseases as well as produce. It was also one of the most densely populated areas in all of China, which suffered from poor sanitation and regular summer floods. Even in the absence of a crisis, a shortage of sources of fresh drinking water meant that many people had to rely on polluted rivers, buying bucketloads from carriers such as the one pictured above. Although drinking water was filtered with alum and boiled, the same precautions were often ignored for cooking and washing. All these factors allowed cholera and other waterborne infections to thrive.

The Water Tower and Ma Lu, Hankow (Wuhan), Stanfield Family Collection, js02-130 © 2015 John Stanfield

A key development in the fight against cholera occurred when an industrialist called Song Weichen 宋衛臣 commissioned a large water tower in 1906. Though this hardly stands out on the vertiginous skyline of Wuhan today, for much of the twentieth century it was the tallest building in the city. It formed the centrepiece of a new Waterworks and Electrical Company, which was supplying around fifteen thousand people with clean drinking water by the mid-1920s. While this went a long way to tackling the problem of water-borne diseases, many of the poorer residents remained beyond the reach of the new urban sanitary regime. The same was true for medical interventions. The first vaccines for cholera were developed in the late nineteenth century, yet only foreign settlers and local elites were able to take advantage of them. As a result of these uneven developments, susceptibility to infectious diseases came to correlate increasingly with economic status. This was true also true in the world beyond Wuhan – as richer communities improved their defences, conditions such as cholera increasingly became a disease of the poor. Until conditions could be improved for every citizens, however cholera would remain a threat.

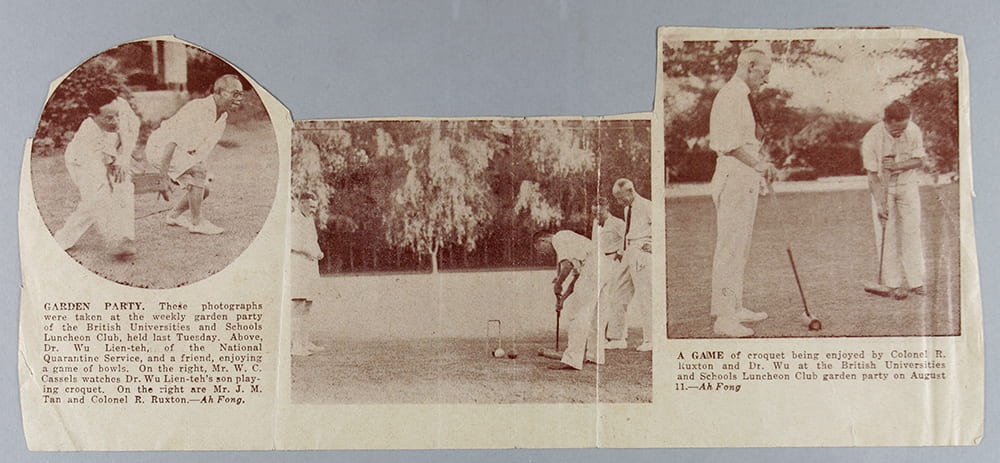

British Universities and Schools Luncheon Club garden party, Ruxton Collection, Ru-s177 © 2008 Penelope Fowler

During the early twentieth century numerous organisations were involved in efforts to eradicate cholera. These included local benevolent halls, foreign missionaries, and organisations such as the Red Cross and Red Swastika. Few figures did more to improve public health in cities such as Wuhan than Wu Liande 伍連德, a Malayan-Chinese epidemiologist who had made his name fighting plague in northern China in the 1910s. In the 1930s, Wu set up one of the branches of his new Quarantine Service in Wuhan. Unfortunately, this new institution could not prevent an outbreak of cholera in 1932. This occurred partly a result of disastrous flooding that had struck much of China the previous year. The 1932 epidemic was the deadliest of the twentieth century, spreading to three hundred cities, infecting one hundred thousand people and killing thirty thousand. It highlighted the continual vulnerability to the China suffered, its public health problems being a symptom of chronic poverty, environmental instability, and political chaos.

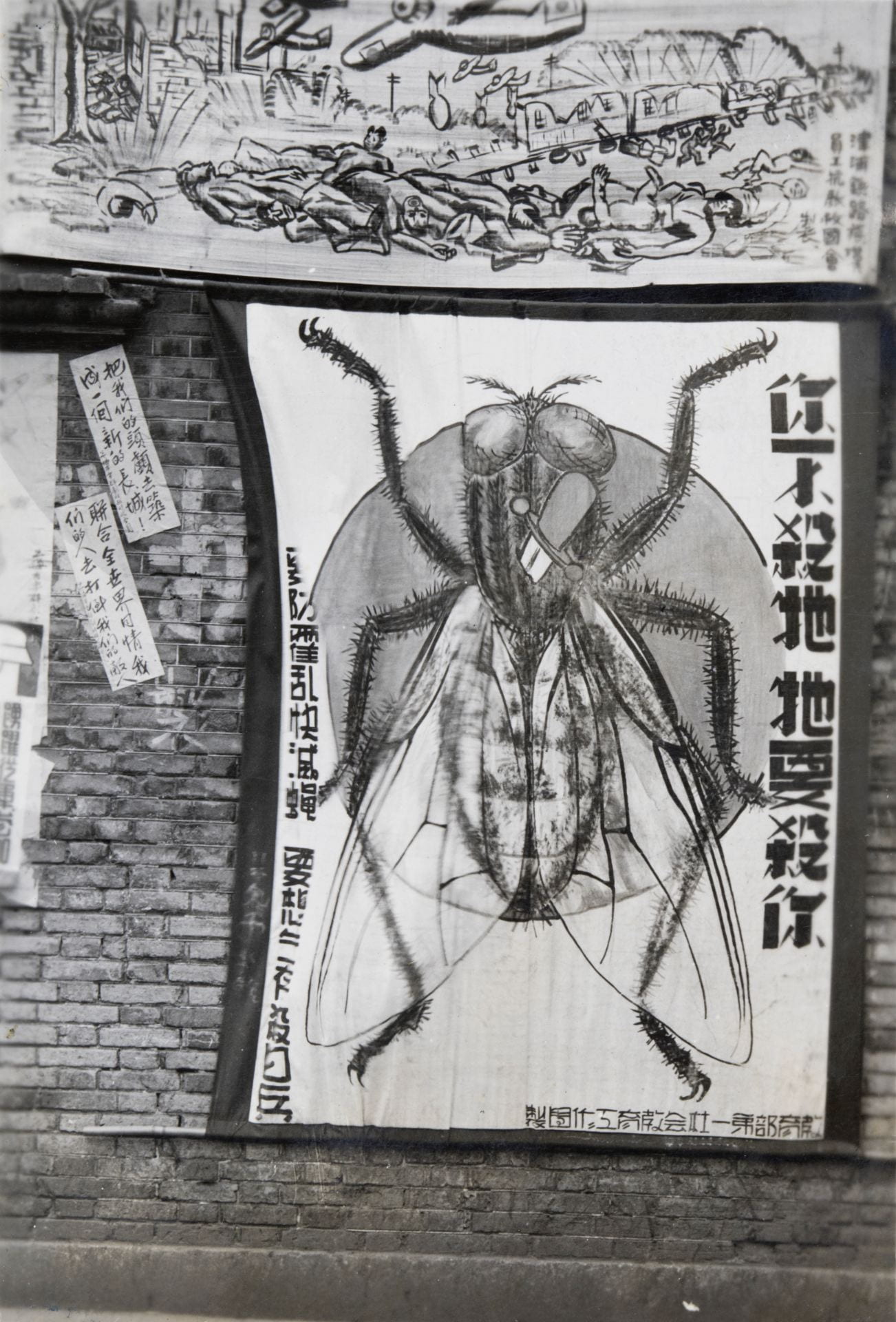

Having witnessed the terrible devastation wrought by the 1932 epidemic, it is not surprising that the Nationalist Government was extremely alarmed when millions of refugees took to the roads to escape oncoming Japanese invasion in 1937. With Wuhan serving as the temporary capital of Nationalist China following the fall of Nanjing, many of these refugees soon began to arrive in the city. Lacking adequate accommodation and suffering aerial bombardments, Wuhan struggled to cope. Soon propagandists began to promote anti-epidemic measures as part of the broader war effort. Flies often serve as a vector for cholera infection. These insects were now portrayed as the equivalent of the invading Japanese army, and vice versa. The Nationalists were hardly unique in drawing such comparisons. As Edmund Russel has noted, throughout the modern era people have sought to anthropomorphize insects, turning them into conscious adversaries with wicked plans, whilst they have also sought to dehumanize enemy soldiers, suggesting that they need to be eradicated like insects. In 1938, the Nationalists claimed that the common fly and the Japanese army both posed an existential threat to China, proclaiming that ‘If you don’t kill it, it’s going to kill you.’

Woman inoculated in the street, Shanghai Malcolm Rosholt Collection, Ro-n0779

© 2012 Mei-Fei Elrick and Tess Johnston

Wuhan eventually fell to the Japanese, meaning that Nationalist anti-epidemic measures were relocated to Chongqing. Tackling cholera remained a major task for the government during the war, particularly when a deadly epidemic struck Yunnan. In her recent book, Mary Brazelton demonstrates that while efforts to implement mass vaccination during the war were severely constrained, the expertise developed during this period would form a vital blueprint for the health campaigns implemented by the Chinese Communist Party after 1949. These campaigns would eventually vastly diminish the impact that cholera, in Wuhan as elsewhere in the People’s Republic. While the Chinese government was happy to take the credit for this, in reality cholera prevention was the culmination of decades of effort, conducted by numerous different organizations, both domestic and international. Despite these efforts, cholera remains a threat in the world today, as is most tragically demonstrated by the ongoing outbreak in Yemen. The strain of cholera has changed, yet the context for its transmission – poverty, sanitary collapse, and warfare – is strikingly similar to that found in early twentieth century China. Thus, as we enter the age of COVID-19 it is worth reflecting on the fact that we have not escaped the time of cholera.

Some Further Reading

- Brazelton, Mary Augusta, Mass Vaccination Citizens’ Bodies and State Power in Modern China, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2019

- MacPherson, Kerrie, “Cholera in China, 1820–1930: An Aspect of the Internationalization of Infectious Disease,” in Mark Elvin and Ts’ui-jung Liu (eds.), Sediments of Time: Environment and Society in Chinese History, 487–519. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Peckham, Robert, Epidemics in Modern Asia. New Approaches to Asian History, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Poon, Shuk-wah, “Cholera, Public Health, and the Politics of Water in Republican Guangzhou,” Modern Asian Studies, 47(2), 2013. 436-466

- Russell, Edmund. War and Nature : Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring. Studies in Environment and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.