Dr Helena F. S. Lopes is Senior Research Associate in the History of Hong Kong and a Lecturer in Modern Chinese History at the University of Bristol. She holds a DPhil in History from the University of Oxford.

Dr Eleanor Whitworth Mitchell, née Perkins (1882-1974), a London-born and trained medical doctor, arrived in Hong Kong in 1913 and lived there for nine years. Both she and her husband, Dr Isaiah Edward Mitchell (1869-1935), worked for the London Missionary Society (LMS). The photographic collection that survives from the years she lived in the British colony includes a rich array of images of working lives and spaces.

There are several photographs of hospital buildings which later came to form the Alice Memorial & Affiliated Hospitals. These, together with the other LMS buildings, were the spaces which framed her life and work in the British colony. As observed by Moira M. W. Chan-Yeung in A Medical History of Hong Kong, 1842-1941 (Hong Kong: CUHK Press, 2018), the LMS ‘played a major role in popularising Western medicine among the Chinese in Hong Kong’ and its hospitals were central to this. It is likely that Dr E.W. Mitchell followed in the pioneering footsteps of Dr Alice Sibree, who popularised Western maternal health in Hong Kong. The LMS also employed Chinese doctors and nurses and amongst the individual and group portraits in the Mitchell collection there are, for example, two of Chinese midwives with newly born babies (Mi01-009, Mi01-016). Indeed, Eleanor Mitchell’s photographs are evidence of the intense participation of Chinese women in medical care.

Dr Eleanor Whitworth Mitchell with nurses and newly born babies, outside a maternity hospital, Hong Kong. Historical Photographs of China ref: Mi01-016.

The portraits of Eleanor Mitchell and the people around her in her professional life – as a doctor and as a missionary – are mostly arranged and set up group portraits where everyone sits or stands still for the camera. However, the collection also includes a large number of urban outdoor scenes where her lens – for she is believed to have taken most of the photographs – captured people going about their daily lives. These include rickshaw pullers and sedan chair bearers, construction workers, and street hawkers, amongst others. Given the many photographs taken of porters, it seems that she had a particular interest in them. Perhaps the physical strain caused by heavy portering work caught her attention, and professional eye.

Porters carrying wood, and women with umbrellas, Hong Kong. Historical Photographs of China ref: Mi01-033.

These photographs (most of which were not captioned in the album), offer a glimpse into the lives of the anonymous people whose labour literally created the built environment around them, and those – like the rickshaw men – whose bodily strength forged links between local places by moving people around it. In several of these photographs, those captured in the frame seem oblivious to Mitchell’s camera. They went on walking, carrying, holding, selling, chatting. This banal activity is now frozen in time, the camera allowing us to appreciate apparently spontaneous gestures and street scenes. In Mi01-041, a person covers their forehead – perhaps to see better ahead on a sunny day while a man stands with a walking stick and a woman glances at a nearby shop. In Mi01-042, women and children stand outside a stall while porters toil on with their heavy loads. In Mi01-047 rickshaws compete with motor vehicles for road space while the occasional pedestrian is also present. Elsewhere, umbrella-holding women pass by scantily dressed workers, each rushing about their everyday activities (Mi01-033, Mi01-050). Visions of labour share the frame with some of momentary rest: in Mi01-049 and Mi01-050, sedan chair bearers lie down or sit by the side of the street while others continue to work next to them. These snapshots also suggest other changes in the making, for example, in repairs and additions to the urban landscape and the evolution of clothing styles during the first years of the Republic of China.

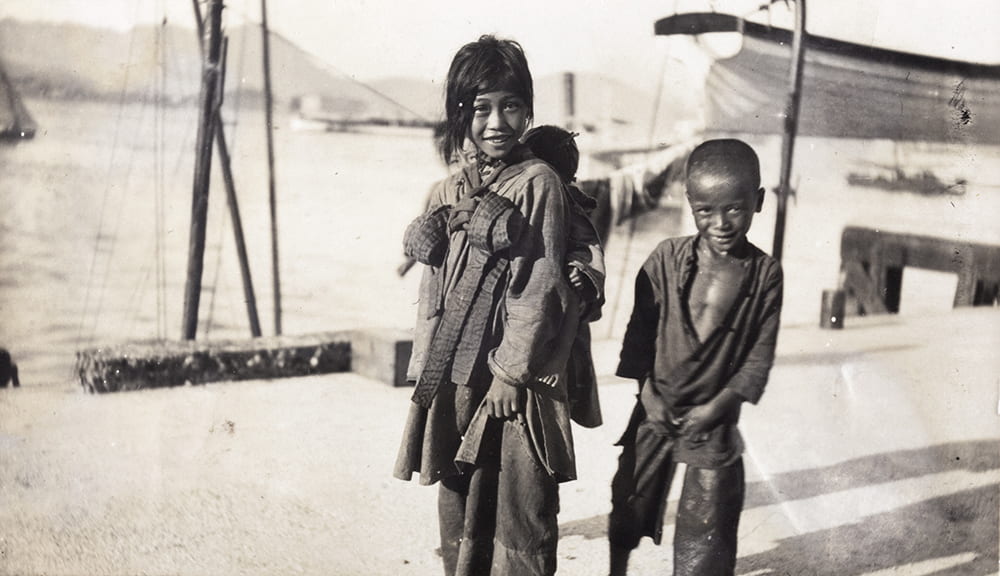

Images of diverse childhood experiences can also be found in the collection’s holdings. In Mi01-044, almost imperceptibly, a group of young girls in Western style dresses get a taste of the buzz of a street market. Elsewhere, injured children convalesce in the hospital accompanied by Dr Mitchell and nursing staff (Mi01-007; Mi01-017). We encounter the reality of child labour, with children carrying different materials and products, possibly for construction or for sale (Mi01-052, Mi01-094). There is also evidence of the role youngsters played in childcare in the image of a girl with a baby on her back (Mi01-063), below.

The Mitchell collection provides material for those interested in the social history of early twentieth-century Hong Kong and South China in general (there are also images of Guangzhou and Lushan). In particular, it serves as an illustration of, and invites further research into, the sometimes-intersecting experiences of women, missionary activities, medical practices, travel, work, and everyday urban culture.

NOTE: If you recognise some of the people, streets, or buildings that remain unnamed in these photographs, we would be grateful for information that would allow us to identify them more thoroughly.