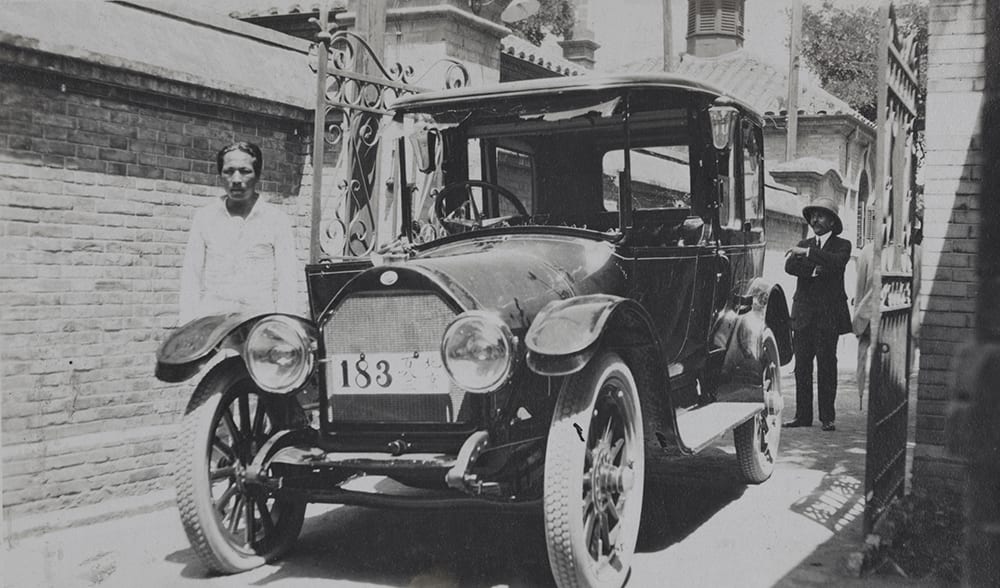

Andrew Hillier explores the story behind a pair of striking photographs in our collection, and in his family’s history.

Guy Hillier’s car parked outside the premises of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, Beijing, with flat tyres, broken windscreen, broken windows, and bullet holes. Richard Family Collection, Historical Photographs of China ref EH01-242.

The images of Guy Hillier’s bullet-ridden car would have been surprising to those who knew him only as the blind and austere agent of the Hongkong Bank’s Beijing office. He was not the sort of person to be caught up in a shoot-out. In fact (spoiler alert), he was not in the car when it was shot at by Peking guards during the twelve-day Manchu restoration in July 1917. It was the Bank’s accountant, R. C. Allen, who, along with the chauffeur and a mafoo (a groom), narrowly escaped death. But Hillier was involved shortly afterwards and also came under fire.

Guy Hillier’s car parked outside the premises of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, Beijing, with flat tyres, broken windscreen, broken windows, and bullet holes. Richard Family Collection, Historical Photographs of China ref EH01-243.

The weather was stiflingly hot – Guy Hillier’s secretary and amanuensis, Eleanor (Ella) Richard, recalled that the temperature was over 100°F – and he was spending the week-end of 30 June at Balizhuang, a Buddhist monastery in the western hills, some four miles outside Beijing, where he had a modest set of rooms. Hearing that the former emperor, the eleven year-old Aisin-Gioro Puyi, had been brought out of retirement and placed on the throne, he hurried back to Beijing on 2 July and cabled A. G. Stephen, the Shanghai manager:

Restoration of Emperor proclaimed yesterday. President [Li Yuanhong] so far refuses to resign and remains in his residence with 2000 men under republican flag …Peking remains quiet with troops of the new regime posted throughout the city. No opposition or disturbance expected in Peking at present, but provincial and Southern opposition probable.[i]

In fact, the calm was short-lived and, amidst much confusion, sporadic fighting began breaking out in the city between Zhang Xun (Chang Hsun), the principal militarist, who had instigated the coup, and troops loyal to the former premier, Duan Qirui (Tuan Chijui). As the events unfolded, Hillier kept Stephen up-dated with a stream of somewhat breathless telegrams. By 11 July, Puyi was still on the throne and, as the city seemed quieter and Hillier was having difficulty sleeping in the heat, he and his mafoo rode back to Balizhuang, having told Allen to meet them at the western gate at 7 a.m. the next morning.

However, waking at about 4 a.m., he heard the sound of gunfire coming from the city and he and his mafoo immediately set off back to Beijing. Having also heard the gunfire, and realising it would be too dangerous for Hillier to return by pony, Allen decided to drive out to fetch him. According to Maurice Collis’ account, as he made his way through the city, the car was shot at ‘without warning or [anyone] calling on the car to stop’. But, Ella recalled Allen telling her a very different story immediately afterwards:

Allen had been going at a fine pace through one of the broad streets near the Palace when an officer commanding some Chinese troops shouted an order to them holding up his hand. The chauffeur wished to stop but A. who could not understand Chinese, called to him to rush through. The chauffeur jammed his foot on the accelerator, and they tore past the officer. He was so enraged that he gave an order to fire. The car was riddled with bullets. The mafoo sitting by the chauffeur was hit in his arm and a bullet passed through the peak of the driver’s cap … They swept safely into the great broad street on the West where, to their astonishment, they found G. and his mafoo riding their ponies.

The car’s petrol tank had been holed and all six men had to make for the safety of the Anglican Mission on foot. Hillier ‘had had to run like a lamplighter through some of the hottest firing’, as he told Ella. It was, he said, ‘an extraordinary experience for a blind man. He could hear the shots and the rattle of machine guns and the ping of bullets but he could also sense that the streets were empty and a strange silence reigned but for the terrific noise’. Even for someone who so relished brinkmanship, the incident shows how foolhardy Hillier could be but also his extraordinary reserves of courage.

Senior bank staff, including Guy Hillier and R.C. Allen, Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, Beijing, c.1923. Standing, from left to right: R.C. Allen (Accountant), Eleanor Hillier, unidentified man (but not Hubbard), D. A. Johnston, name unconfirmed (possibly J.L.T. Patch). Sitting: Guy Hillier. Guy and Ella were married in Hong Kong on 20 December 1919. Richard Family Collection, Historical Photographs of China ref EH-s63.

In the event, with the help of a modest payment to Zhang’s troops, the coup ended late that evening and the emperor’s twelve-day reign was over and Duan resumed the office of premier. The following day, according to Ella, one of his representatives called and apologised for what had occurred. ‘They refunded the loss of Allen’s burberry and one or two things stolen from the car and paid compensation to the mafoo for his wound and spoiled clothing’. Most important of all, they presented Hillier with a new car.[ii]

[i] Based on Hillier’s telegrams, the story is told by Maurice Collis in Wayfoong: The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (London: Faber, 1965), pp. 145-50, but, in 1934, when Puyi was made a puppet emperor in Manchuria, Eleanor (Ella) Isabella Hillier (née Richard) wrote her own account, ‘Pu Yi’s Twelve Day Reign or the Battle of Peking’ (Private Collection).

[ii] I am grateful to Jennifer Peles for allowing me access to Ella Hillier’s papers and to quote from them.