Dr Andrew Hillier discusses the China photographs of John Thomson (1837-1921) in the light of a recent exhibition of his work at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS.

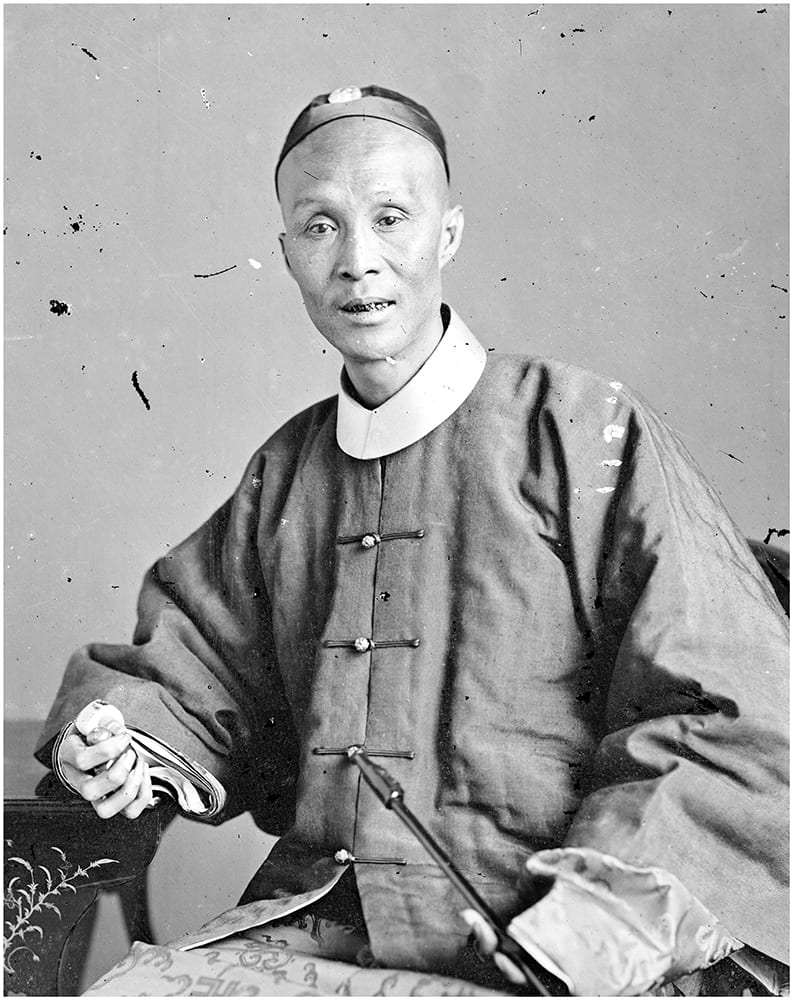

One of two hundred images published in John Thomson’s Illustrations of China and its People, the ‘Cantonese official’, seen in figure 1, fixes the viewer with a look as intense as it must have been when he faced Thomson’s camera in 1869.[i] Magnified to many times its original size, it provided a particularly striking image in the recent exhibition of Thomson’s photographs of Siam, Angkor (Cambodia), Hong Kong and China, held at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS. Accompanied by two talks and a study-day, the exhibition provided an opportunity for a major re-assessment of Thomson’s work in East and Southeast Asia and its legacy.[ii] Excellently displayed, with stunning images of landscape and people, it confirmed that Thomson was, as Jamie Carstairs said in his earlier blog, ‘probably the greatest of the nineteenth century photographers of China’.[iii] However, as the picture of this Cantonese official shows, the exhibition also raised questions about the role of a Western photographer in China during the treaty port era and how such work should be displayed today.

Fig. 1. Listed simply as ‘a Cantonese Gentleman’, the photograph was described by Thomson as ‘a salaried official who in process of time became … a mandarin of the sixth grade’, Illustrations of China, I, plate 22. Photograph by John Thomson, negative no. 650. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY.

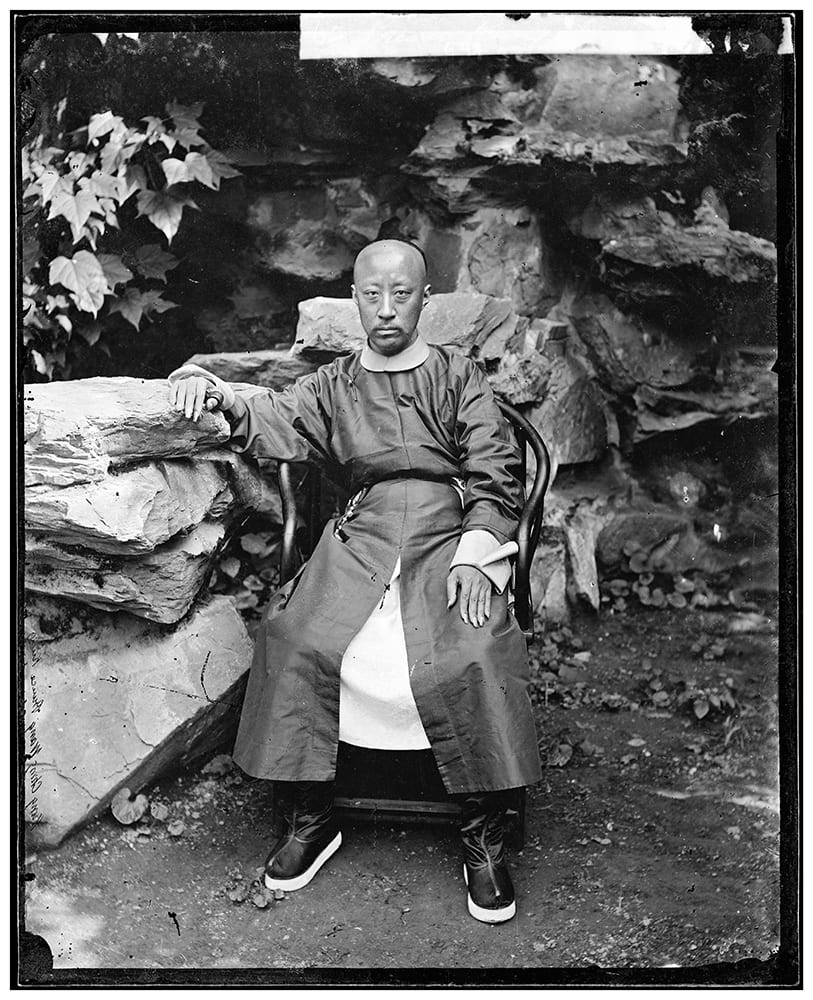

Unlike Thomson’s formal portraits of officials such as Prince Gong (Figure 2) and members of the Zongli Yamen, this more low-grade official is un-named. This is because, as with many of Thomson’s photographs, the purpose was not to portray an individual but to exemplify a particular Chinese ‘type’. Moreover, the image does not conform to the conventions of Chinese portraiture: the full face is not shown, part of it being in shade and, only the top half of the body can be seen.[iv] This suggests that, although the official must have agreed to being photographed, it may not have been done at his request and the resulting image may well not have met with his approval.

Fig. 2. Listed as ‘Prince Kung, China’, this is a formal portrait of Prince Gong, sixth son of Prince Daoguang, Illustrations of China, I, plate 1. Photograph by John Thomson, negative no. 692. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY.

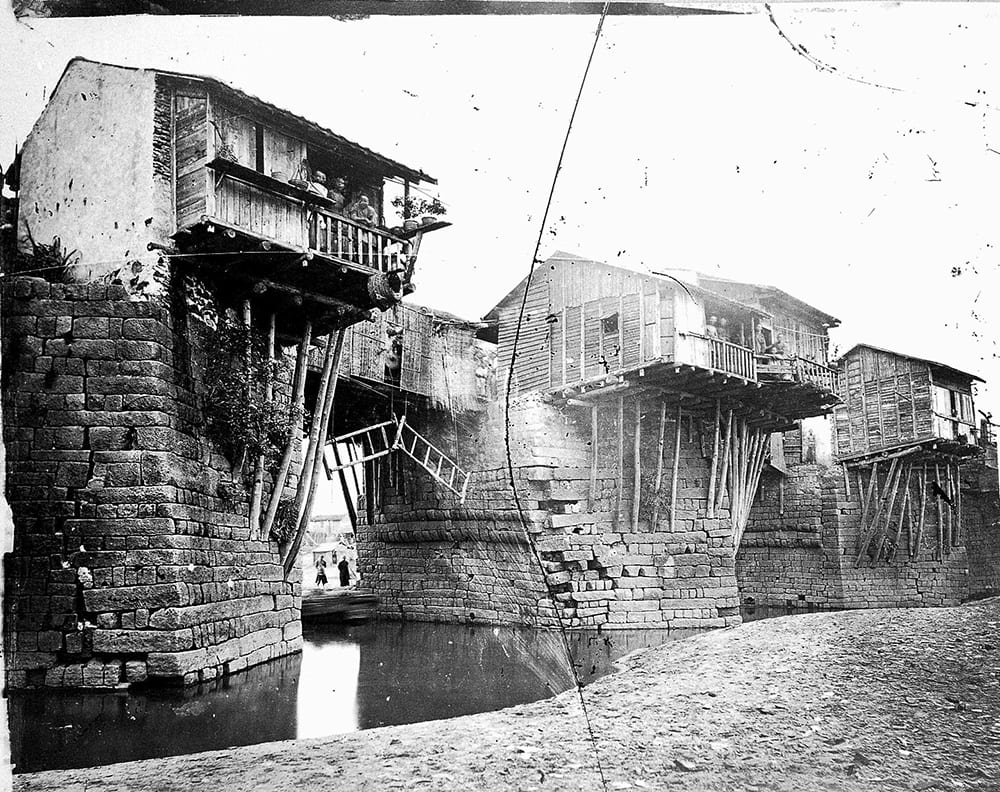

This is not something that would have worried Thomson. It is clear from his commentary to Illustrations of China that, however, sympathetic he was towards Chinese people, he could often be superior and high-handed, amused by, but brushing aside, their fear that he was ‘a dangerous geomancer and that [his] camera was … a darkly mysterious instrument which … gave [him] power to … pierce the very soul of the natives’. As a result, Thomson often encountered, but was seemingly unperturbed by what he saw as, ‘the hatred of foreigners’, especially in and about large cities, such as Canton (Guangzhou) where this mandarin held office. On one memorable occasion, when photographing a bridge in Chaozhou, Guangdong province, he came under a hail of stones, one cracking the wet plate in the camera and causing him to beat a hasty retreat but not before he had taken the shot.[v]

Fig. 3. Chao-chow-fu Bridge, Kwangtung. Groups of people gathered on the bridge and began throwing stones. A vertical crack can be seen on the glass plate. The photograph appears in Illustrations of China, II, plate 8. Photograph by John Thomson, negative no. 290. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY.

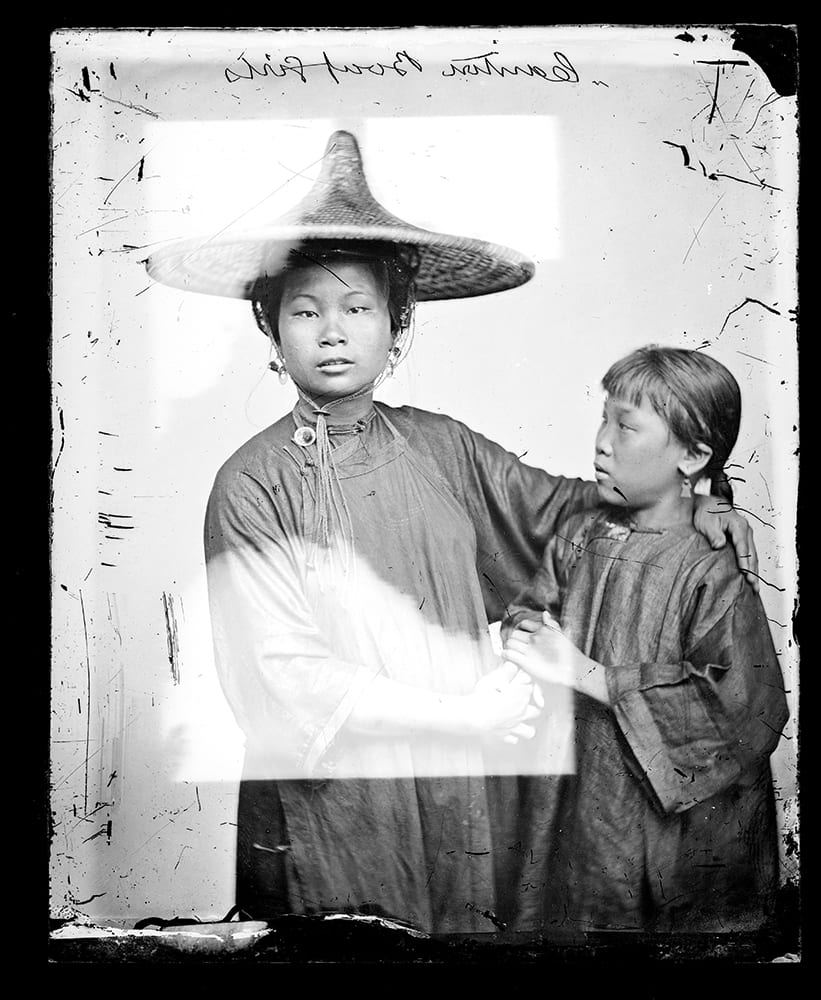

On the other hand, Thomson was obviously an excellent communicator and established a good rapport with many of his subjects, whether they were Chinese officials posing in their formal robes or street vendors plying their trade. Critical of Qing officials, as a social commentator, he developed a great sympathy for these ordinary people, particularly the boat-women of Hong Kong and Canton, who certainly seem to have been willing to pose.

Listed as ‘boat girls’ in Illustrations of China, I, plate 7, this photograph was taken in Kwantung in 1869 and was one of a number of boat women around Canton and Hong Kong. Photograph by John Thomson, negative no. 684. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY.

It was an interest and sympathy that would later inform Thomson’s study of London street life.[vi] However, as with so many of these types of Victorian image, there is a disturbing tension between the depiction of such subjects, whether on the streets of Peking (Beijing) or London – coster-mongers, gamblers, beggars, and street vendors – and the aesthetic pleasure derived from viewing them in lavishly-produced volumes. [vii]

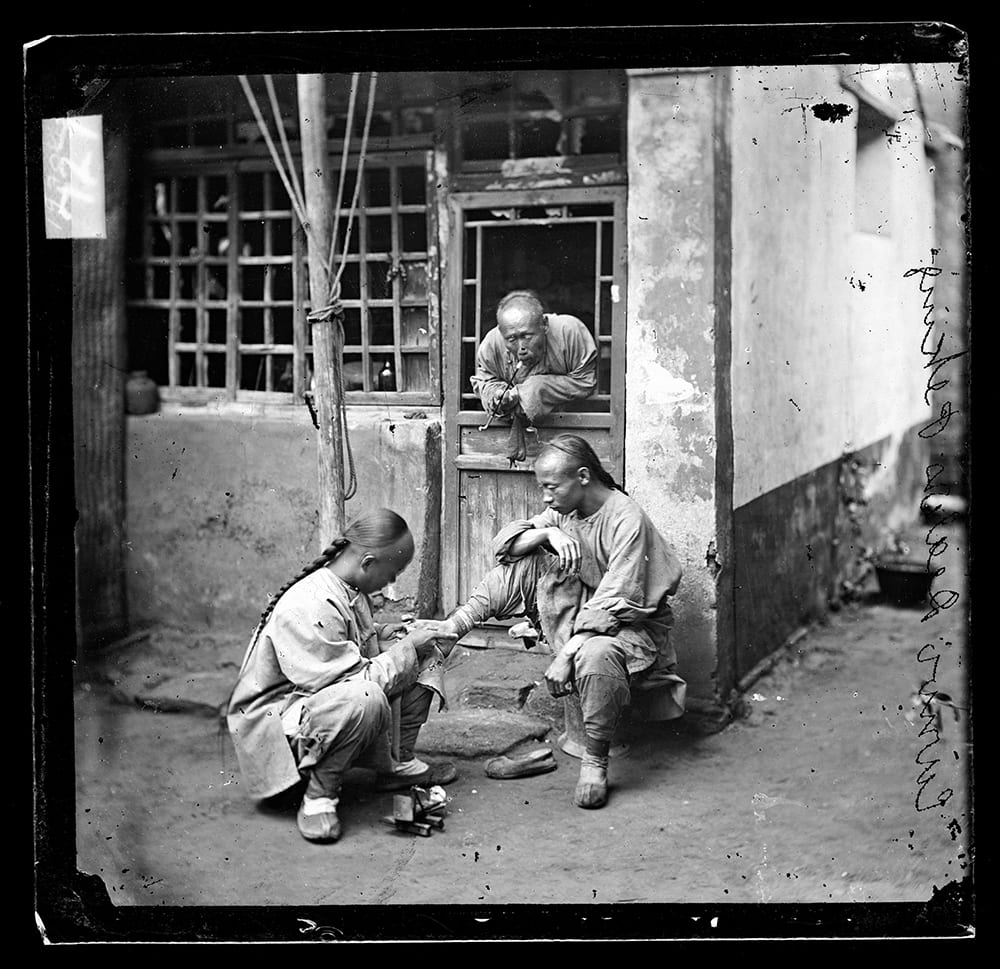

Fig. 5. One of a group of four ‘medical men’, the photograph shows a chiropodist in Beijing tending one patient, whilst another waits his turn. It appears in Illustrations of China, IV, plate 11. Photograph by John Thomson, negative no. 727. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY

Fig. 6. Listed as ‘one of the city guard, Peking’, the photograph shows a night-watchman with his wooden board, used to sound that all was well: ‘wrapped in his sheep-skin coat and in an under-clothing of rags, he lay through cold nights on the stone steps of the outer gateway and only roused himself to answer the call of his fellow-watchmen near at hand’, Illustrations of China, IV, plate 22. Photograph by John Thomson, negative no. 688a. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY.

If these images raise difficult questions today, as Thomson’s biographer, Richard Ovenden, reminded the audience in his entertaining lecture, to understand his work, we must start with his upbringing and early training in Edinburgh, a city where diligence and intellectual fervour were highly-valued.[viii] He probably first learned about photography during his apprenticeship to an optician and scientific instrument- maker, James Mackay Bryson, and then, impatient to start earning his living, set off for Singapore, where he arrived in May 1862 to join his brother, who had established a watchmaker’s business. Realising that photography was the way forward, Thomson spent the next eight years working in Southeast Asia and the China coast, returning to Britain from time to time.

Between 1870 and 1872, Thomson travelled extensively in China, before finally leaving Asia in the summer of 1872. Throughout this time, he used the wet-plate collodion process, a cumbersome exercise entailing dangerous chemicals and a substantial amount of bulky equipment, but which allowed for shorter exposure times and, in skilful hands, could produce high resolution images that recorded the finest detail. Although he is to- day chiefly known for the illustrated books that resulted from his travels, during these years, he was principally working as a commercial photographer, supplying the western community in Hong Kong and the treaty ports, with portraits and cartes de visite.[ix]

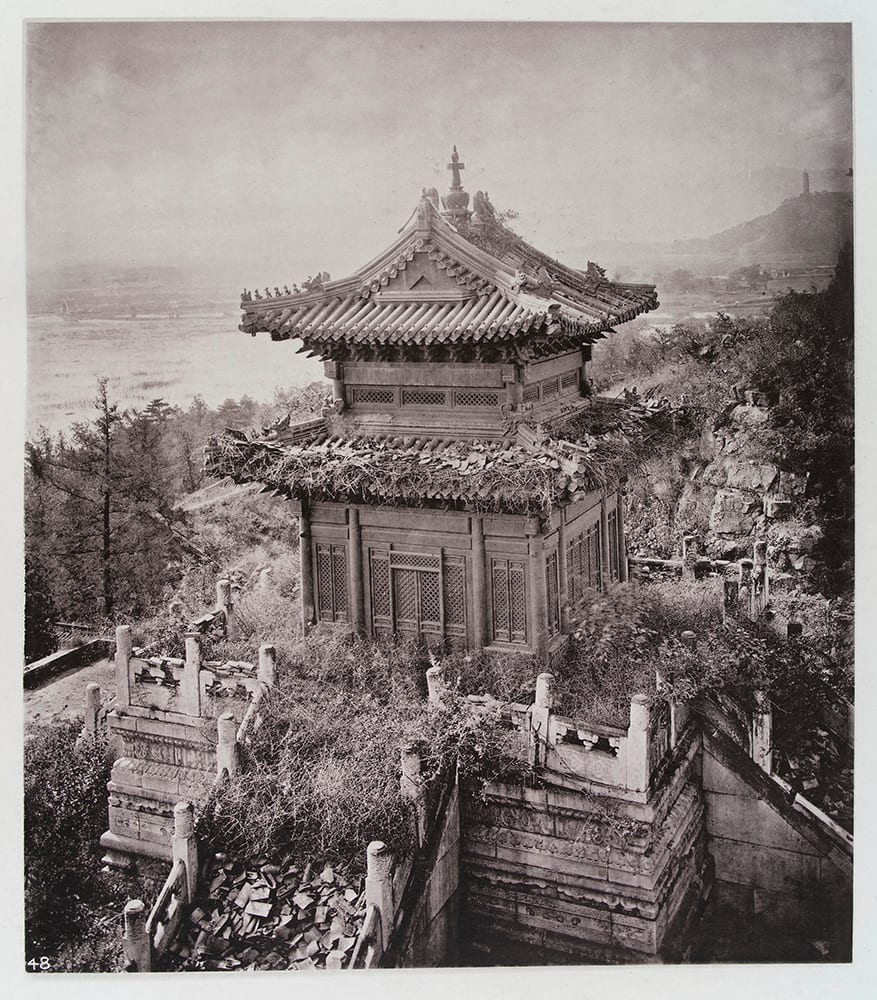

For Thomson, it was not just the photographs but also the accompanying text that was important. He wanted to inform and instruct and ‘share the pleasant experience of coming face to face with the scenes and people of far-off lands’. This included images of the continuing conflict between China and Britain, embodied in the ruins of the Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan) destroyed by the British in 1860 (Figure 7), and the Chapel of the Sisters of Mary in Tientsin (Tianjin) where ten French nuns had been murdered in 1870 (Figure 8).

Fig. 7. The Bronze Temple, Yuen-min-Yuen at Wan-shou shan. One of the few buildings remaining in the ruins of the Summer Palace destroyed by the British in 1860. ‘Left ruinous and desolate designedly as one means of keeping the hostility of the nation active, and as an ever-ready witness to the barbarities to which foreigners will resort; many educated Chinese have that feeling and look upon our conduct as an event of heartless vandalism’, Illustrations of China, IV, plate 19. Photograph by John Thomson. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY.

Fig. 8. Chapel of the Sisters of Mary, which was destroyed, following the murder of ten French nuns in 1870, Illustrations of China, IV, plate 3. The photograph was probably taken not long afterwards in early 1871. Photograph by John Thomson, negative no. 528a. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY.

If Thomson never sought to question the validity of Britain’s presence, his attitude towards China was ambivalent. Whilst critical of what he saw as the corruption and obfuscation of Qing officials, he nevertheless could see the country’s potential. Beside the image of three officials entitled, ‘The Government of China’, he told the reader, ‘Western nations have woken the old dragon from her sleep of ages, and now she stands at bay armed with iron claws and fangs of foreign steel.’

It is difficult to gauge how much influence his work had on the understanding of China in Britain at the time. Although well-received, the four volumes of Illustrations of China were prohibitively expensive and accessible to only a few. Being commercially-minded, he kept pace with the changes that were taking place in the mass-production of books and magazines, including the more sophisticated forms of wood engraving of photographic images (Figure 9). He wrote and published extensively, particularly in the Graphic and the Illustrated London News, and produced cheaper versions of his work, the most popular being With a Camera in China.[x]

Fig. 9. Travelling chiropodists: a wood engraving based on the image at fig. 5. Drawn by E. Ronjat and engraved by T.H. Hildibrand, it formed one of the illustrations in a cheaper more accessible version of Illustrations of China, viz: John Thomson, The Land and People of China: a Short Account of the Geography, Religion, Social Life, Arts Industries and Government of China and its People (London: SPCK, 1876). Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC.BY.

In normal circumstances, this might have had some influence but, by the late 1890s, relations with China were at a low ebb. As western nations and Japan competed for large swathes of its territory, the Boxer Movement was gathering pace, culminating in the Siege of the Legations in 1900. Thomson’s photographs would soon be overtaken by a new wave of images, depicting the devastation following the Siege and the public execution of Boxers and their alleged associates, and that also raise questions about display and interpretation today.[xi]

The after-life of the photographic image was a recurring theme during an intense and varied study-day – the initial developing and cropping (at which Thomson was particularly adept), its use in books and magazines, and as a political and social instrument, and its display and interpretation over the course of time. This recent exhibition displayed Thomson’s images in a way that neither he nor his subjects could have envisaged. With such high-quality negatives, the magnification undoubtedly enhanced their impact and the resulting detail of the formal portraits and landscapes was quite breath-taking.[xii]

But in the case of the more intrusive images of Chinese ‘types’, the process is possibly more questionable. If, as Nick Pearce has said, ‘these photographs of the natives may make us feel uncomfortable’, arguably this discomfort can only be increased by such magnification. Coupled with Thomson’s moving text, images such as that of the night-watchman become all the more distressing.[xiii] Moreover, taken, as they were, against a frequently hostile background and recorded in lavishly-produced books, they are emblematic of Britain’s imperial presence in an era that is still officially described as ‘the century of national humiliation’. Does this way of showing them not implicitly legitimise that presence?

That there is no easy answer to these questions is clear from the image of the Cantonese official (Figure 1). On one view, the enlargement has increased the sense of objectification. But on another, it has helped to transcend his anonymity and enhance his individuality. We know little about him but, for many viewers, his face and the intensity of that look will have remained with them long after they had left the gallery. This may be the measure of Thomson’s skill, not only as a photographer but also as a communicator.

[i] J. Thompson, FRGS, Illustrations of China and its people: a series of two hundred photographs with letterpress description of the places and people represented (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low and Searle, 1873-1874). For Thomson, generally, see Richard Ovenden, John Thomson (1837-1921): Photographer (Edinburgh: The Stationery Office Ltd, 1997) and Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China: Western Photographs, 1861-1879 (London: Quaritch, 2010), pp. 214-256. For Thomson’s China photographs, see China: Through the Lens of John Thomson, 1868-1872 (Bangkok: River Books, 2010), the second edition of the catalogue originally prepared for the exhibition of the forerunner of this exhibition at the Beijing World Art Museum in 2009.

[ii] ‘China and Siam: Through the Lens of John Thomson’, Brunei Gallery, SOAS, 13 April – 23 June 2018 ; ‘John Thomson: Reframing Materials, Images, and Archives, 7 June 2018’. The original negatives are held at the Library of the Wellcome Collection and are accessible on-line. This exhibition will next be shown at Bournemouth starting on 3 November.

[iii] Jamie Carstairs, ‘Restoring John Thomson’s Grave’, Visualising China, 31 May 2018, https://hpchina.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2018/05/31/restoring-john-thomsons-grave/

[iv] Cf. Tong Bingxue, ‘John Thomson: a Humanist View of the World in China’ in China: Through the Lens of John Thomson, 1868-1872 (Bangkok: River Books, 2010), p.10 and the commentary to the plate on p.119.

[v] For the quotation, see Introduction to Illustrations of China and, generally, James R. Ryan, Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1997), pp. 61-68 and 161-167.

[vi] Adolphe Smith and John Thomson, Street Life in London: With Permanent Photographic Illustrations (London: Sampson, Low, Martson, Searle and Rivington, 1877-78).

[vii] Cf. Ovenden, Thomson, pp. 72-109 and Ryan, Picturing Empire, pp. 173-180.

[viii] Richard Ovenden, ‘John Thomson: Master Photographer’, SOAS 14 June 2018.

[ix] Ovenden, Thomson, pp. 1-5 and 167-175. Only a handful of the cartes de visite can be traced to-day as Angela Cheung explained in her study-day paper, ‘What is a photograph? Reflections on Thomson’s Carte de Visite production in China’.

[x] Through China with a Camera (London: Harper, 1899), Ovenden, Thomson, pp. 175- 183.

[xi] James Hevia, English Lessons: The pedagogy of imperialism in nineteenth-century China (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 195-240.

[xii] For a detailed discussion of Thomson’s formal portraits and landscapes, see Ovenden, Thomson, pp. 109-166.

[xiii] Nick Pearce, ‘John Thomson’s China: 1868-1872’, in China, p.8.