Following a recent visit to the Royal Hampshire Regiment Museum in Winchester, Dr Andrew Hillier discusses the rich resources that are available in such museums and their importance to the study of imperial history.

There are well over one hundred small museums in Britain dedicated to displaying the history of individual army regiments. These contain rich sources of material relating to the country’s colonial past. But regimental history and how to display it can be problematic, given the tension between the mission of such institutions to uphold the honour of the regiment and critical perspectives on imperial history that contest the values it was committed to enforce.[i] The dichotomy is exemplified by the 67th (South Hants) Regiment of Foot, which spent four years in China in the early 1860s, first fighting the Qing government during the Second Opium War and then supporting it against the Taiping rebels, events which are recorded in both its excellent museum display and in Historical Photographs of China. How should these events be remembered so as to do justice to those who took part in them whilst at the same time recognising their unacceptable features? In order to answer that question, it is first necessary to explore how they were understood and recorded at the time. The purpose of this blog is to show what a rich resource such regimental archives can constitute for this purpose, and how important it is that they continue to be valued and made accessible at a time when some have already closed and others are at risk.[ii]

Despatched from India after the British had suffered ‘a stinging humiliating defeat’ at the Taku (Dagu) forts in June 1859, the 67th distinguished itself the following year, when, along with the 99th, it stormed the North Taku Fort on 21 August 1860, an engagement which quickly led to the fall of Tianjin and the end of the Second Opium War.[iii] Of the six Victoria Crosses won that day, four were awarded to the regiment – to Lieutenant Edmund Lenon, Lieutenant Nathaniel Burslem and Private Thomas Lane, who, having swum the 18 foot wide ditch, broached the walls under intense fire, and to Ensign John Chaplin who was the first to plant the colours at the top of the defences. Their heroic deeds form a major part of the museum display, being commemorated in photographs, medals and citations, together with pictures and an account of the attack (plate 1).

To give further context, the display has summaries of their subsequent careers, the misfortune, which dogged Lenon and Chaplin, being reflected in the history of their medals: both were pawned and only recovered through the goodwill of the regiment and others.[iv] Whilst the commentary is well-judged, some might question the lack of any explanation relating to items looted from the Summer Palace (Yuanming yuan) – two silver cups and, hanging nearby, a fine five-clawed imperial dragon embroidery, albeit there is a label somewhat blandly stating that it was ‘taken from the Summer Palace by Colonel Bell Kingsley’.[v]

1. Part of the Taku Fort display, Royal Hampshire Museum. Note the copy of one of Beato’s photographs, the history of Lenon’s VC and the two silver cups looted from the Summer Palace (author’s photograph).

The display includes copies of photographs taken by Felice Beato, the Italian war photographer, who had already made his name in the Crimea and the aftermath of the Indian Uprising. Famously insisting that the corpses not be removed until he had completed the exercise and, at times, even adjusting their position for effect, this was the first time that dead soldiers had been photographed on the battlefield. Whilst there are originals of some of Beato’s pictures in the museum archive, their provenance is uncertain. Those in HPC come from the album of Captain George Thomas Atchison of the 67th , who took part in the attack and who may well have purchased them before Beato left China in November 1861 (plates 2 and 3).[vi]

2. The Upper North Taku fort stormed by the 67th on 21 August 1860. The wooden pontoon had been laid by sappers. Ahead of it are the fixed defences of iron and wooden stakes ‘thick as the pins on a pin-cushion’ and beyond them, the 18 foot wide ditch which the first attackers had to swim before the drawbridge was lowered into position. Photograph by Felice Beato. GA01-038.

3. The interior of the upper north Taku fort shortly after the attack. This was the first time that dead bodies had been shown as part of the documentation of war. Photograph by Felice Beato, GA01-041.

The display is supplemented by the regimental archives – a rich assortment of photograph albums, scrapbooks of press cuttings, which include lithographs of Beato’s pictures, and other memorabilia, journals and correspondence. The letters from Ensign Lorenzo Mosse to his mother are of particular interest as they describe the prelude to the attack – a 5-hour march, often knee-deep in mud, with corpses strewn along the way and bivouacking in the open – and then the attack itself – ‘the slaughter was tremendous, there were 29 [Chinese] dead round one gun’.

4. Ensign Chaplin at the moment of regimental glory. Note the ‘handkerchief’ of the tricolour below it. A copy of the painting forms part of the museum display. The artist, date, and whereabouts of the original are unknown (copyright, Royal Hampshire Regiment Trust).

According to this account, Chaplin was somewhat fortunate to win his VC, as ‘this lucky youngster happened to be next to’ the ensign carrying the colours, seized them when the ensign was ‘knocked over’, and ‘with the leading men, made a rush for the top of the Cavalier [vii] and succeeded in planting the Union Jack [sic]’. For Mosse, who did not have a good word for the French, the important point was that Chaplin got there ‘before they could get up with the tricolour which is about the size of a pocket handkerchief’ and it was this that earned Chaplin his VC. However, this does him less than justice, as, according to the regimental historian, C. T. Atkinson, having planted the colours, ‘thrice-wounded, he still pressed on, men of the 67th crowding after him’.[viii] Recorded in a somewhat gaudy oil-painting (plate 4), this was a defining moment for the regiment, not only for its own history but also for a wider public, as the events were the subject of at least five published eye-witness accounts, the titles of which tell their own story.[ix]

Moving north, the regiment was stationed on the outskirts of Beijing, where it participated in the looting of the Summer Palace, and then, as the war drew to a close, it returned to Tianjin. In addition to the group photographs in plates 5 and 6, the museum also has an album containing thirteen sheets of cartes de visite portraits of members of the 67th. These will have been exchanged between officers and provide an early example of what became an extremely popular medium and a further rich source for the regiment’s history. [x]

5. Officers of the 67th, Tientsin, 1861. By this time, the war was over and the men have a relaxed, not to say somewhat dishevelled appearance, some with straggly beards reminiscent of those who fought in the Crimea. (GA01-035).

6. Officers of the 67th, Tientsin, 1861. The loucheness and swagger in their demeanour suggests a pride in the VC’s which had been announced in August 1861 (GA01-036).

In April, 1862, some nine officers and 320 men from the 67th were transferred to Shanghai where they linked with other British forces, charged with enforcing a 30 mile exclusion area around the city and assisting the Qing against the Taiping rebels, alongside what became known as the Ever Victorious Army.[xi] They were joined in August the following year, by a young ensign, John Eyles Blundell, recently arrived after a four month voyage from England. He had already begun writing his journal and compiling an album of photographs, which would cover his time in China and subsequent military service in Japan, Burma and Afghanistan. Whilst the journal does not refer to the pictures, the consistency of many of the images suggests that at least some were taken by him. If this is correct, he should be seen as a significant and, hitherto unrecognised, photographer of a regiment in empire. [xii]

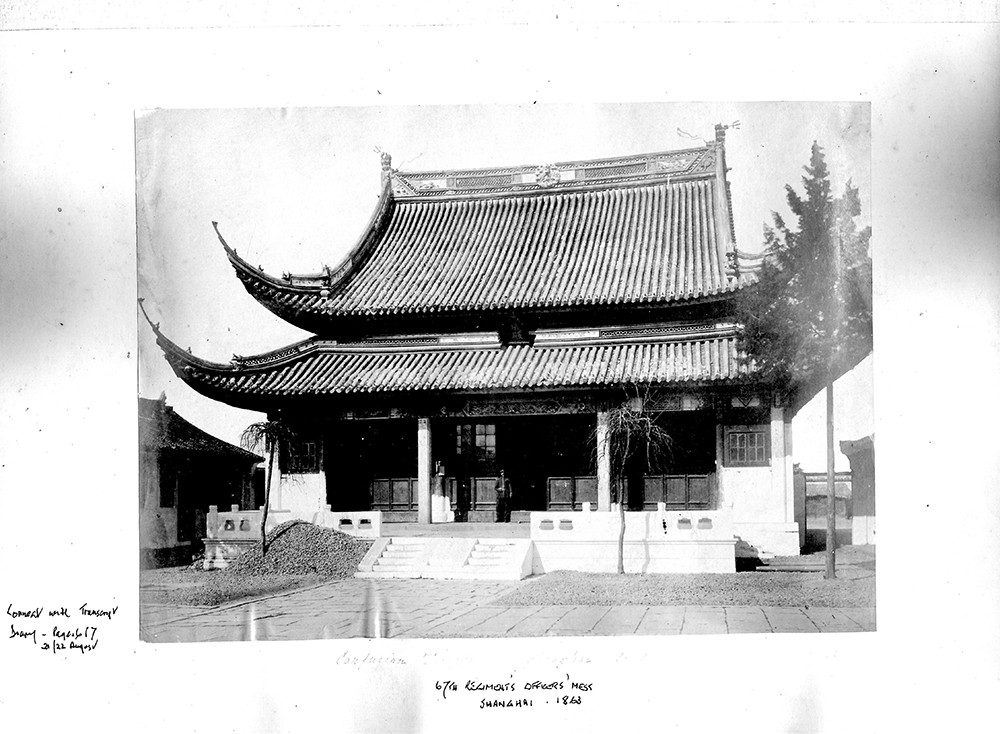

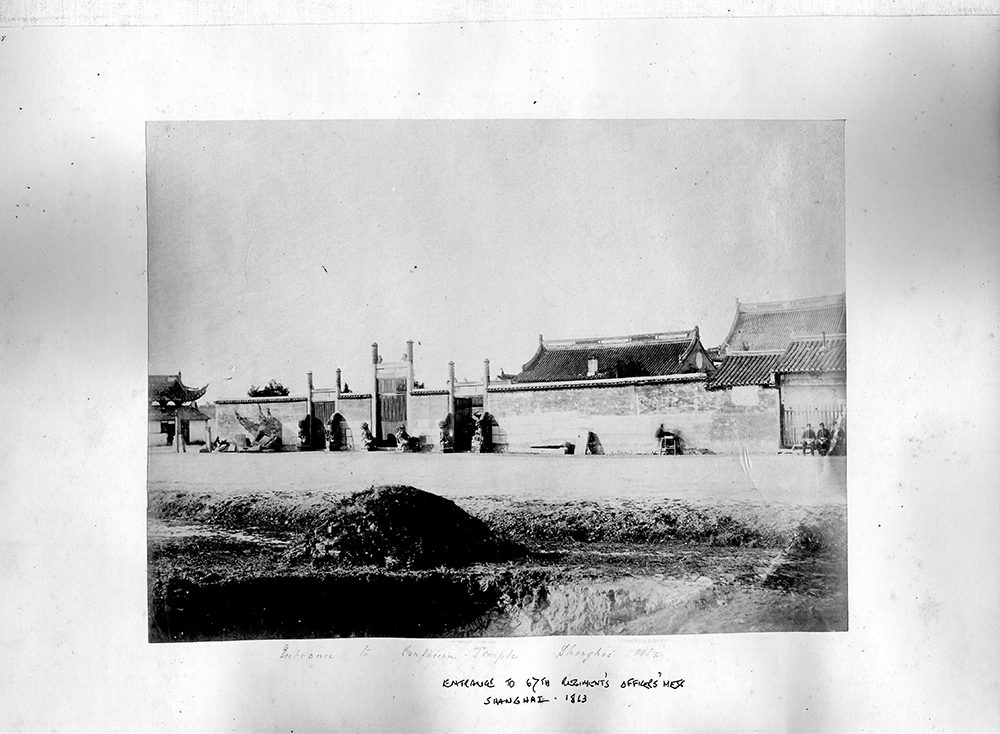

On arrival, as he recounts, he had difficulty locating the officers’ quarters: ‘Given a Chinese guide, set forth – a “short-cut” follows through Chinatown – stinks- almost unendurable- narrow and crowded streets – Cholera is rampant’. The headquarters turned out to be ‘a Joss House’.[xiii] Here, some distance from the foreign settlements, he and his fellow officers spent the next twelve months, stationed amongst the Chinese whom the regiment was there to protect (plates 7 and 8).[xiv]

7. 67th Regiment’s Officers’ Mess in the Confucian Temple, Shanghai, 1863. ‘All the fellows seem very agreeable’, wrote Blundell in his journal (Blundell album, copyright Royal Hampshire Regiment Trust).

8. Entrance to officers’ mess, Shanghai, 1863 (Blundell album, copyright Royal Hampshire Regiment Trust).

Although he was not engaged in any combat, Blundell witnessed the three months’ siege of Suzhou by combined forces under the command of General Charles ‘Chinese’ Gordon. On at least two occasions Gordon came to dinner with Blundell and, at the end of the evening, ‘had out his artillery and shelled and fired rockets into the city – it looked very jolly by night’. In December, 1863, Blundell witnessed the storming of the city – ‘lost a great many officers and men … The slaughter inside the city was fearful. Two officers of the 99th went in after the place was taken – got plenty of loot and many valuable silks etc.’[xv]

Five months later, he returned to explore Suzhou, examining the walls where the final assault had been made and then climbing the nine-storied pagoda. There were ‘splendid views of the surrounding country’ but on the ground it was less savoury: the landscape ‘devastated on all sides by the Rebels – hundreds of people in a state of starvation, and dead bodies all around’.[xvi] By 1864, the rebellion was nearing its end and, in July, the regiment received orders to embark for Japan. Three companies, the Artillery and some sappers boarded an American steamer, the Takiary, – it was ‘fearfully hot’ and they were ‘packed like herrings – all the baggage, men’s packs and guns piled on deck’.[xvii]

They left behind comrades who had died both in the fighting and from cholera, but these three years of the regiment’s history have gone largely unrecorded. [xviii] Perhaps, this was because they lacked glamour but also because of a feeling that, in assisting a country which the regiment had so recently been fighting, the glory of the Taku fort engagement might be diluted. Yet, defending Shanghai and the half million Chinese who had fled to the foreign settlements in the city for shelter, was an important phase in both the regiment’s and Britain’s imperial story. As well as seeing active service, officers and men had had to contend with extremely trying conditions and to experience the strangeness of a country that they described in their journals and in their letters to their families and friends at home. It is a story worth remembering, even if there were no comparable acts of valour.[xix]

If the Taku engagement became enshrined in regimental memory, for Lieutenant-Colonel Lenon, as he became, it held little comfort. Retiring in 1869, he then suffered heavy losses from speculating on the stock exchange in the 1870s. Forced to pawn his VC and dying in penury, he was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery in an unmarked grave. However, family and regimental pride combined to ensure that the medal was recovered and that, in 2007, a suitable gravestone was laid on his burial plot (plate 10).[xx]

9. Lieut. Colonel Lenon’s new headstone, Kensal Rise Cemetery (Copyright, Royal Hampshire Regiment Trust).

How this history will continue to be remembered, however, is an open question, given the fact that, in 1992, the Royal Hampshire Regiment, which included the former 67th, became part of the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

10. Royal Hampshire Museum, Serle’s House, Winchester (author’s photographs).

Whilst those transferring from the Royal Hants’ have continued to identify themselves with the old regiment, recruits to the Princess of Wales’ have no reason to do so. Inevitably, there is a risk that interest in its distinguished history may fade. Leasing a suite of rooms in the elegant Georgian building that used to be its Lower Barracks, the museum and archive are currently in safe hands but their long-term future is not guaranteed.[xxi] They constitute an invaluable source not only for those connected with the regiment but also, more widely, for anyone interested in Britain’s imperial past, whatever their political hue. The importance of such records, some of which have already ceased to be readily available, needs to be recognised. As a move towards making them more accessible, the museum has kindly agreed to permit the Historical Photographs of China project to digitise its China campaign photographs. With these sort of collaborative initiatives, there is plenty of cause for optimism in the future of these museums.

[i] Cf. John M. Mackenzie, Museums and Empire: Natural History, Human Cultures and Colonial Identities (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), p. 13.

[ii] During my visit to the museum, I was greatly assisted by Lt Col. Colin Bulleid, Secretary of the Royal Hampshire Regiment Trust, who, despite a busy schedule, guided me through the archives and answered my many queries. For the museum web-site, see www.royalhampshireregiment.org.

[iii] Robert Bickers, The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914 (London: Allen Lane, 2011), pp.141-150 and James Hevia, English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-century China (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 31-48.

[iv] The display includes Lenon’s pawn-ticket showing he received 10 shillings in return. An original Victoria Cross today fetches well over £100,000. The originals are safe under lock and key and only replicas are shown.

[v] For the looting of the Summer Palace, see Hevia, English Lessons, pp. 74-102; for similar instances of China loot being displayed in regimental museums, see P. Bruce, ‘Relics of Hong Kong and China in British Army and Regimental Museums’, Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1 January 1983, Vol.23, pp.196-201 and Katrina Hill, ‘Collecting on Campaign: British Soldiers in China during the Opium Wars, Journal of Historical Collections (2013) 25 (2): 227-252.

[vi] For a description and the definitive catalogue of Beato’s work in China, see David Harris, Of Battle and Beauty: Felice Beato’s Photographs of China (Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1999), pp.24-34.

[vii] A military term for the top of a fortification.

[viii] Letters, Lorenzo W. Mosse to his mother, 6, 17 and 25 August 1860 (M1776); see also C.T. Atkinson, Regimental History: The Royal Hampshire Regiment (Robert Maclehose & Company Limited, University Press, Glasgow, 1950), pp.309-313 and http://www.royalhampshireregiment.org/about-the-museum/timeline/67th-regt-assault-taku-forts-china/, accessed March 2017.

[ix] J.H. Dunne, From Calcutta to Pekin: being notes taken from the journal of an officer between those places (London: S. Low, 1861), re-published by the Rifles (Berkshire and Wiltshire) Museum, Salisbury, (2002 and 2011), Robert Swinhoe, Narrative of the North China Campaign of 1860; containing personal experiences of Chinese character, and of the moral and social condition of the country etc. (London, Smith Elder and co. 1861), G.J. Wolseley, Narrative of the war with China in 1860 (London: Longman, Green and Roberts, 1862), David Field Rennie, The British Arms in North China and Japan: Peking 1860; Kagoshima 1862 (London: John Murray, 1864). They also differ as to what colurs Chaplin did plant. Captain Dunne, 99th, in his account, asserts that he, Dunne, was the first to plant the Union Jack, pp.38-39. According to the museum web-site, it was the Queen’s Colour which Chaplin planted.

[x] Wellesley Thomas album (M1503).

[xi] Bickers, Scramble for China, pp. 178-179.

[xii] For other examples of photographs taken by military personnel during the war, principally around Canton, see the National Army Museum Collection (1964-10-121).

[xiii] The term used for a Confucian temple, joss meaning a Chinese god or idol.

[xiv] Ensign John Eyles Blundell, HM’s 67th Regiment, Part 1, January 1863- July 1864, entry, 21 August 1863. This is a semi- verbatim transcript of the manuscript original (M2788).

[xv] Blundell, entries, 28 September and 9 -10 December, 1863.

[xvi] Blundell, entry, 29 May 1864.

[xvii] Blundell, entry, 22 July 1864.

[xviii] They are briefly mentioned by Atkinson in his Regimental History, pp.316-318 but not by Alan Wykes, The Royal Hampshire Regiment(37/67th Regiments of Foot) (London: Hamilton, 1968), cf. pp. 75-82.

[xix] I will discuss the memorialisation of those who died in China in a future blog.

[xx] A presentation booklet was prepared for the occasion (M3929).

[xxi] The premises are currently leased from Hampshire County Council who, I understand, are very keen to support the museum’s future.