The Historical Photographs of China team recently visited “The Chinese Photobook’’ exhibition at the Photographers Gallery, London. Digitization Assistant, Alejandro Acin reports:

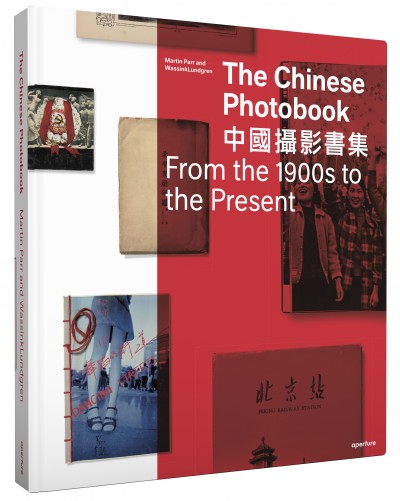

The exhibition is based on a collection of photography books, compiled by Bristol-based photographer Martin Parr and the Dutch photographer duo WassinkLundgren (Thijs groot Wassink and Ruben Lundgren).

Inspired initially by Martin Parr’s interest in propaganda and socialist realism, and as part of his ongoing research into the history of the photobook around the world, Parr went to Beijing to meet Ruben Lundgren. They visited Beijing flea markets in search of photobooks, as well as buying items online. After a year they had made sense of the many surviving publications, grouping them in different categories and periods. Martin said that to acquire the books, it was essential to have someone based in China, who spoke Chinese and had a Chinese bank account. Ruben, being a Beijing resident with an interest in Chinese contemporary photography, was the perfect candidate. Their Chinese photobook collection quickly expanded, forming the basis for a major research project, the exhibition and The Chinese Photobook published this year by Aperture and the China Photographic Publishing House.

China has a long tradition of publishing photobooks, in a variety of approaches and styles, as a consequence of the country’s political twists and turns during the last hundred years. This richness of form, content and authorial perspective is captured in The Chinese Photobook. The exhibition is divided in six sections, includes key publications from as early as 1902, through to contemporary formats by emerging Chinese photographers.

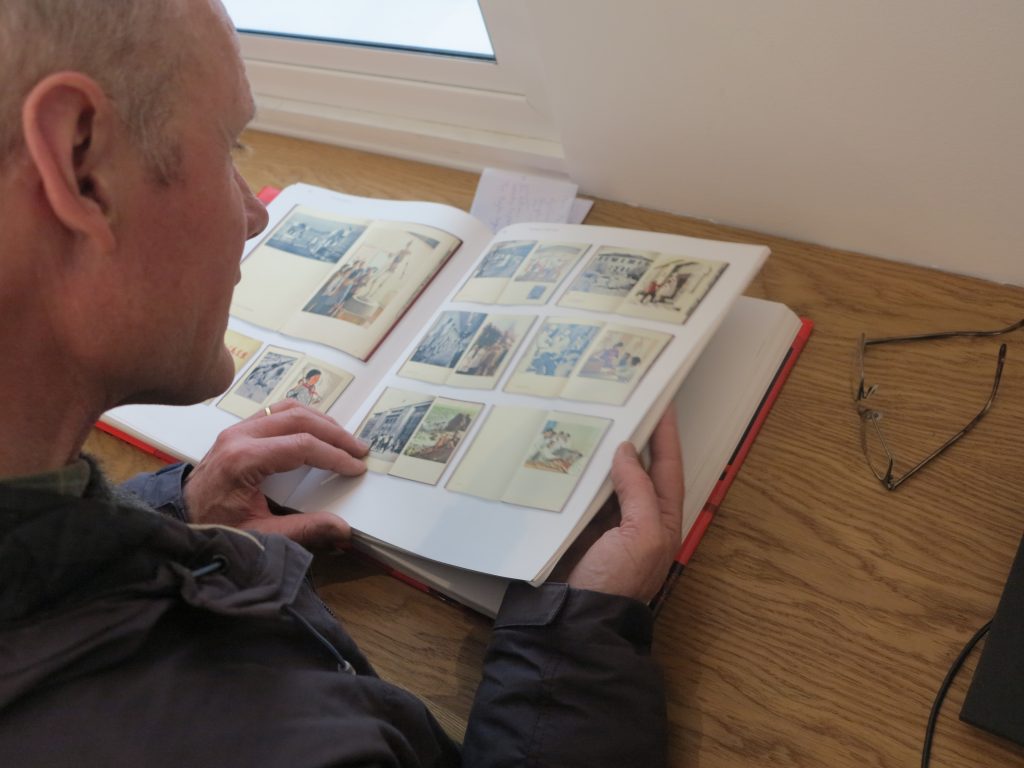

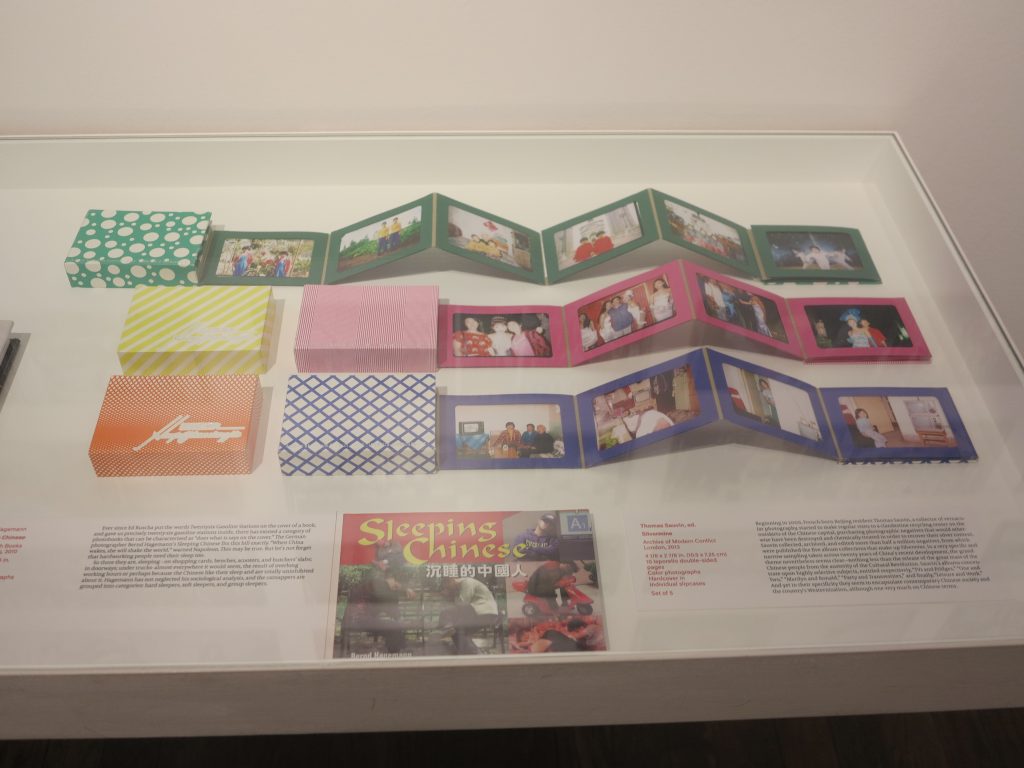

The exhibition offers a glimpse, a tight selection, of what you can find in the eponymous book. WassinkLundgren noted the difficulty of showing photobooks in an exhibition. Collectable photobooks are normally presented in vitrines, where visitors can see only one or two spreads. In this exhibition, WassinkLundgren have combined this display method, with a variety of others, showing the complexity of the publications and facilitating enhanced engagement with them. There are books in vitrines, as enlargements on panels, on screens, as well as being available to touch, smell and physically engage with. Copies of The Chinese Photobook and interviews with the authors are also available in an interactive library.

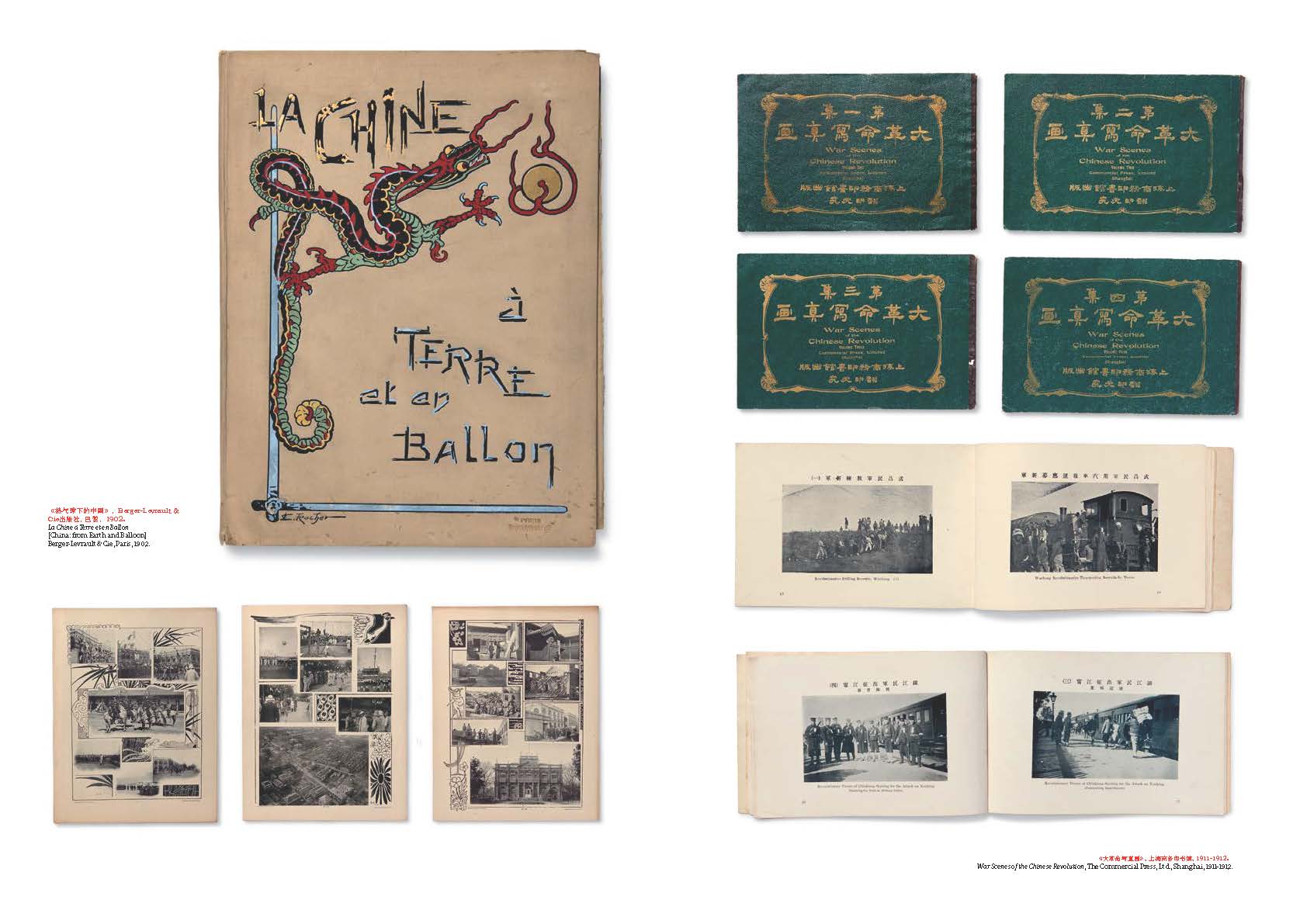

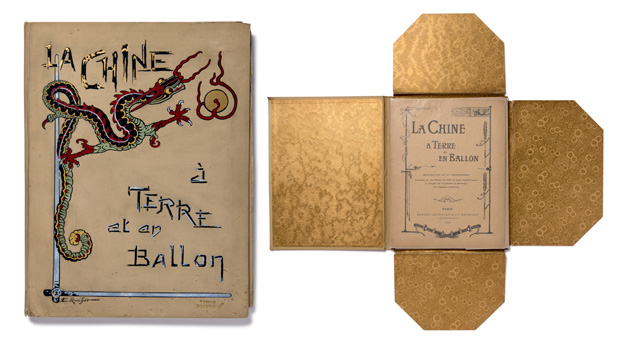

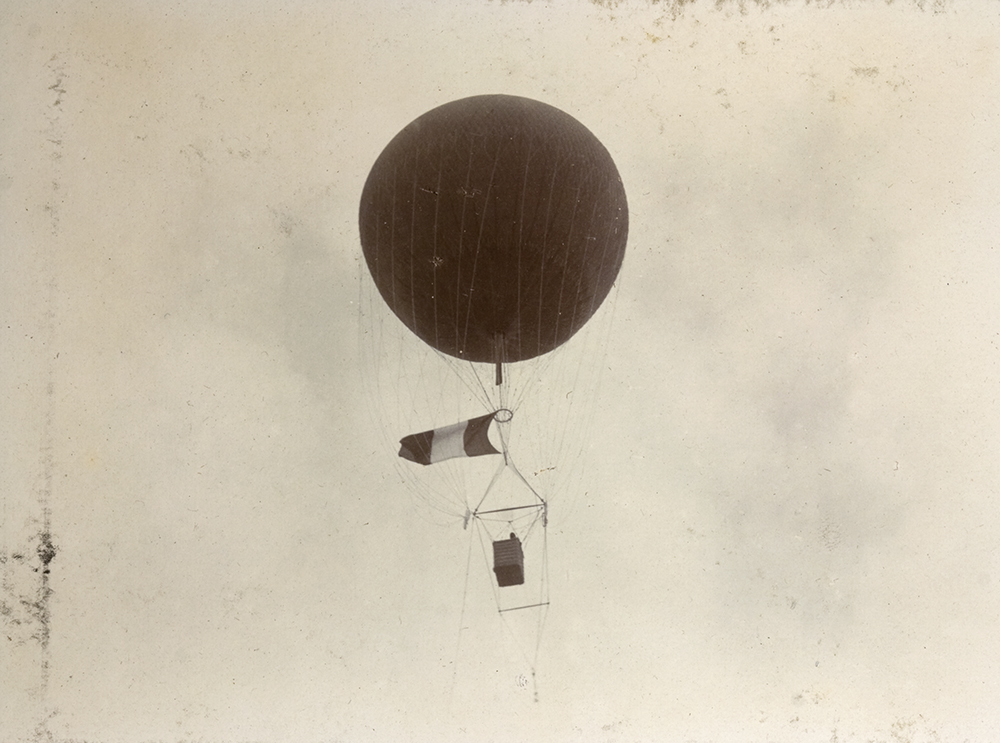

Raymond Lum, and Stephanie H. Tung both contributed to The Chinese Photobook. Lum, formerly Librarian at the Harvard-Yenching Library, and now Resoures editor of Trans Asia Photography Review, explores how imperialist agendas in China in the early twentieth century gave way to the People’s Republic of China. For example, French forces in China during the Boxer Uprising took the earliest aerial photographs of the country, which were reproduced in a loosely bound “clever” book (which could be taken apart and rearranged), adorned with Art Nouveau flourishes: La Chine à terre et en ballon (See a photograph of the French army engineers’ observation balloon).

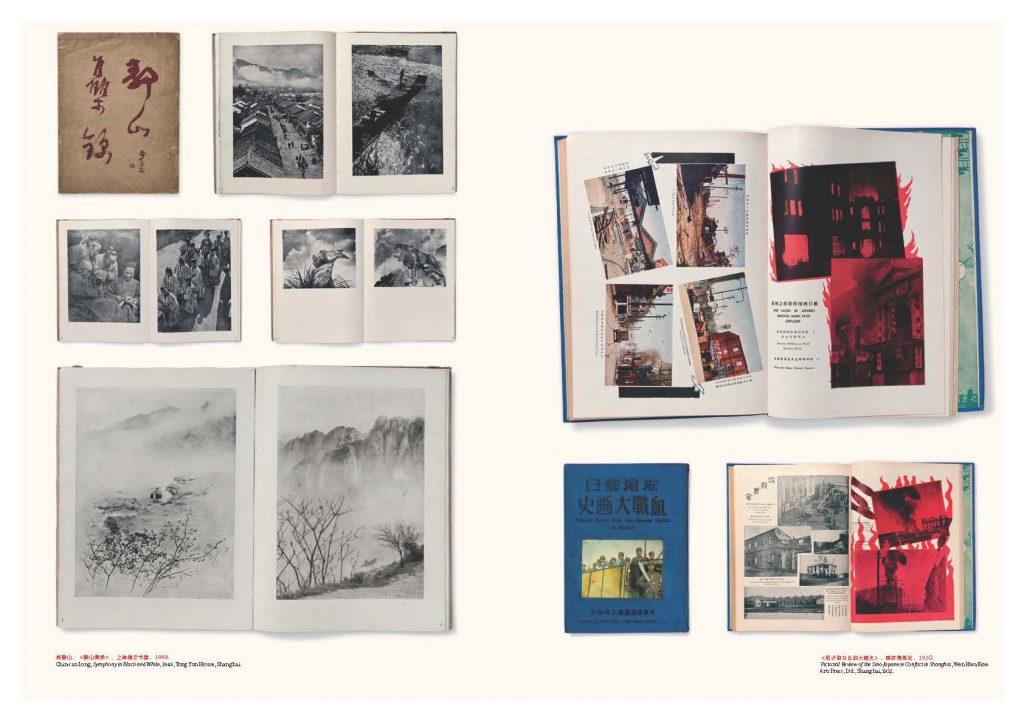

Tung, who is working toward a dissertation on the history of photography in China, writes about the period between 1931 and 1947, which produced photobooks reflecting more artistic practices, as well as books depicting the effects of the Sino-Japanese war. Tung highlights the work of Lang Jiangshan, arguably one of the most famous photographers in Chinese history, who pushed limits of representation in the 1930s and 1940s. Of his layered negatives of landscapes and nudes, Tung remarked that the photographer aimed to evoke the texture of classical Chinese landscape paintings: “He’s trying to express a Chinese essence through photography.” The Japanese publishers introduced some of the first propaganda-style photobooks, lauding occupied Manchuria. Books by Chinese publishers chronicled a nation torn apart by war.

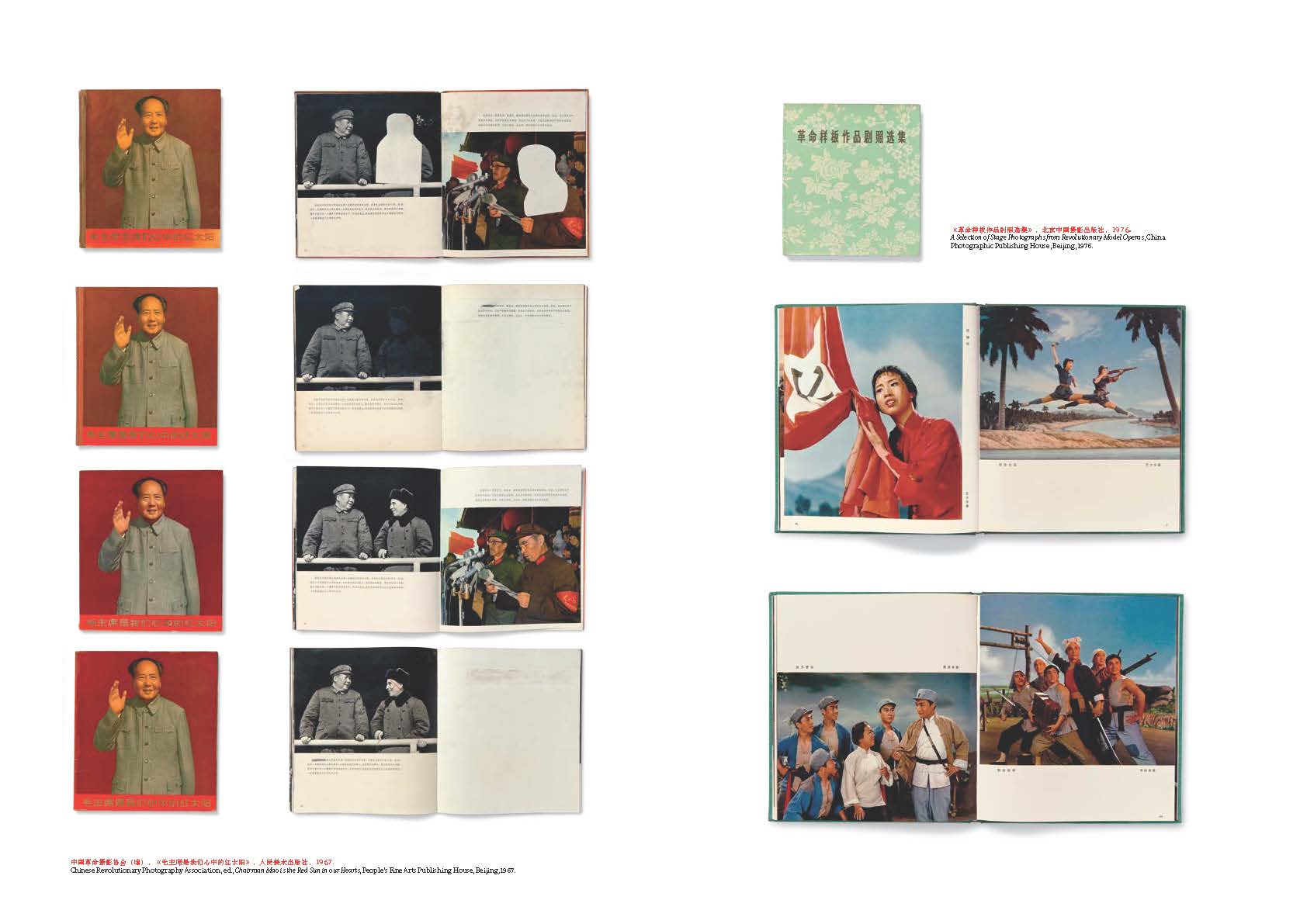

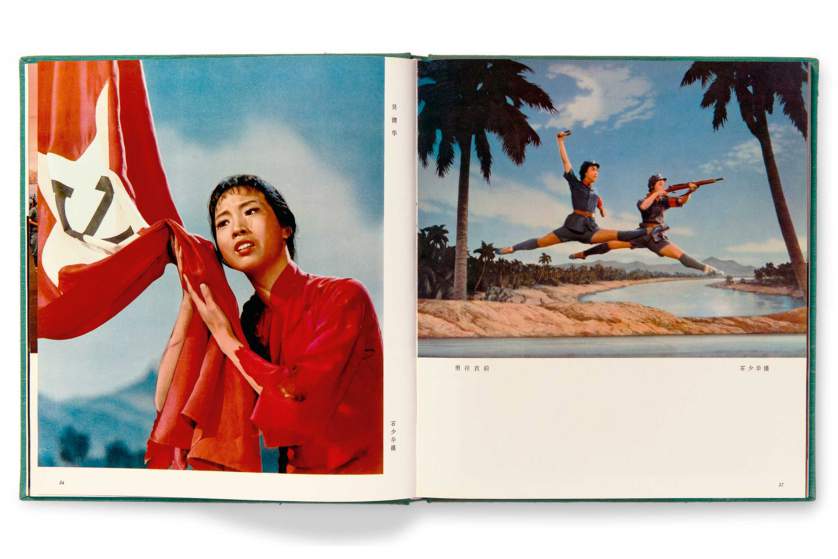

Lundgren, of WassinkLundgren, illuminated Chinese Communist propaganda in the post-1943 period that preceded the rise of Mao. Photography remained extremely important, promoting an image of a prosperous China. Mao even had his own personal photographer. Joyous, but largely anonymous, images of progress characterise the period. The Cultural Revolution of 1966 brought about its own unique style of imagery, emblazoned with portraits of the communist leader. “What you’ll see is, I collect these books, all different times of censorship, especially crosses,” Lundgren added, pointing to an image of Mao and another man, who has been cut out of the image. “It’s a very good example of the craziness of its time.” Thijs also observes: ”This shows that photography is never innocent, it has always a purpose”.

After Mao’s death Chinese photobooks changed dramatically, and photographers began to capture scenes of public grief. “You see the first instances of young photographers not working within a particular political ideology, not on political assignments, creating their own photobooks,” Tung said. Also on view is the catalogue from China’s first free photography exhibition during this period. “We see photobooks go from completely commercial to experimental to die-hard journalism,” Lundgren added. “It goes in every single direction imaginable.”

After Mao’s death Chinese photobooks changed dramatically, and photographers began to capture scenes of public grief. “You see the first instances of young photographers not working within a particular political ideology, not on political assignments, creating their own photobooks,” Tung said. Also on view is the catalogue from China’s first free photography exhibition during this period. “We see photobooks go from completely commercial to experimental to die-hard journalism,” Lundgren added. “It goes in every single direction imaginable.”

In part of the contemporary section, we see fabulous work such us Modern Times by the Taiwanese Patrick Tsai, and the publications of Thomas Sauvin’s Silvermine, alongside some other quirkier publications, like Chinese Sleeping.

The exhibition provides only a glimpse into a fantastic collection of books. One wants to see more: the exhibition is not enough. This visitor would love to have seen the setting they had at the Rencontres d’Arles, where this book was firstly exhibited, and where visitors had to use torches to see the books in the darkness. What I really know is that after seeing this exhibition I cannot wait to have a copy of The Chinese Photobook and start digging into it. Who knows, maybe it can be an inspiration for the Historical Photographs of China project to produce a series of photobooks in the future showing the richness of family photograph albums as a historical contribution?

“The Chinese Photobook” exhibition finishes on 5 July 2015.