Our collections are generally identified with a single individual, in most cases the woman or man who lived and worked in China, and who provides the current owner’s family link to China. In some cases we can certainly state with great confidence that the images in, for example, the G. Warren Swire or Fu Bingchang collections, were taken by Swire or by Fu. We know that they were adept amateur photographers, and we have often been working with their negatives, rather than prints. But the collections of photographs brought to us are often in fact amalgamated from a great variety of different sources. We are now so used to thinking of our family or personal collections of photographs as being taken by us, that we forget that for most of the history of photography so far this has not been the case.

The albums we receive and copy are often collections of photographs that have been purchased from photography shops and studios (as postcards would now be bought), commissioned from photographers, or otherwise acquired from work, or from friends. In many cases we might find that only a minority of images, if that, have actually been taken by the man or woman whose name we have assigned to the collection. (They might well have been taken by other members of the family). Shop-bought images would be cheaper: no need to purchase a camera, and film, and to pay for processing costs. Photographs bought from a shop are also likely to be technically better, and could show sights and scenes to better effect than might otherwise be caught. We might now assume that a photograph we took ourselves would be a more authentic record of our experience, but this was not necessarily a view held by visitors or residents in the past.

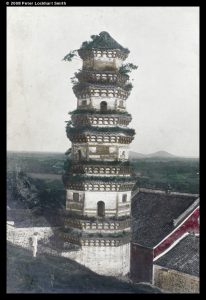

We see this most obviously in one sub-category of photographs that are quite pervasive: images of executions, including the 1904 and 1905 executions by slow-slicing (lingchi) of Wang Weiqin and Fu Zhuli in Beijing, the execution of the pirates of the ship the Namoa in 1891, and executions carried out in the 1920s and 1930s in Shanghai. These turn up across different collections, and sometimes lead some current owners to believe that their ancestor witnessed the events. This is usually not the case: the photographs have been bought. While this is the most dramatic example of the practice, many other images in people’s collections were also purchased from shops, and advertisements in newspapers and guidebooks highlight the fact that shops and studios had images to sell. We do have less unpalatable examples across our collections, such as these below, of a man posed eating rice from a bowl, and of a pagoda near Fuzhou. This does not detract at all from the quality and unique interest of the collections that we have seen — or that you might have. It is instead a complication that makes them all the more interesting, and which sheds light on the social history of the photograph, and the history of these documents as objects.