Concluding his overview of the recently digitised Pirkis Collection, Dr Andrew Hillier digs further into these 400 cartes de visite to consider what the collection tells us about the legation world and the European presence in Peking more generally during the 1870s and early 1880s.

As we have seen, children in the Legation spent much of their time away from their parents. It seems from one of Bessie Pirkis’s paintings, that, by Christmas 1877, Amy and Georgie, now aged six and three, each had their own amah and this certainly will have given Bessie more time for her music and art. For Christmas 1877, she made sketches of a large number of the principal European figures in Peking. In addition to a self-portrait, the series comprised eight women and thirty-two men. Presumably, it was done by way of a Christmas gift for each of the sitters and, although identifying them has proved difficult, it most probably included all the officials in the British legation. At some point, perhaps before they were distributed, the individual images were assembled for the purpose of the photograph in Figure 1.

1. A photograph of portrait sketches of foreigners by Bessie L’Evesque Pirkis, Peking, 1877. HPC DH-s019. Bessie is three along four down, Albert is five along four down and Stephen Bushell may be two along four down. There is a photographic portrait in the bottom right-hand corner. Unknown photographer.[1] Save for those of Albert and Bessie, no individual sketches have been traced.

Bessie captured her subjects in a variety of poses but all in profile, some more formal than others – the women all seem to have had their hair carefully prepared and the men are smartly dressed but somewhat more casual with one reading a book. It perhaps says something for Bessie’s standing that she was able to persuade all of them to sit for her – a lengthy process, given the care with which they have been executed – but, no doubt, they were delighted with the results.

Hart was not amongst the sitters – he was probably too busy and too impatient – but some Customs men and their wives may have been, as the photograph comes from the collection of David Marr Henderson (1840-1923), who as the Engineer -in-Chief in the Marine Department was responsible for the design, construction and maintenance of China’s developing network of light-houses from 1869 to 1898.[2] The fact that he presumably acquired the album at about this time raises a number of questions: how many copies of the photograph were made, to whom were they distributed and why would the photograph be of particular interest to him? Whatever the answers, we can be confident that the exercise will have established Bessie as a leading figure in Peking’s small ex-patriate world.

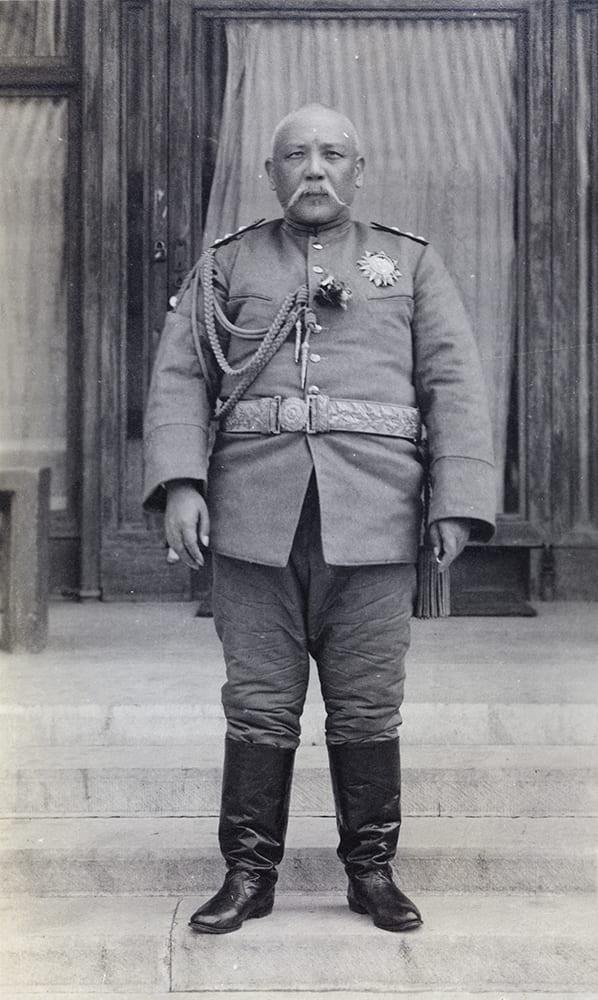

With Albert due a year’s furlough, once Christmas was over, the two of them began preparing for the family’s departure. They set off towards the end of March, full of excitement, but, on reaching Shanghai, were greeted by the tragic news that the Chinese Secretary, Frederick Mayers, who had arrived with his wife, Jeannie, and two children just days before them, had succumbed to what was described as ‘typhus fever’- a catch-all phrase for many illnesses but, in his case, one certainly exacerbated by over-work and Peking’s harsh climate.

2. Frederick Mayers. Undated. HPC PF-s0206

A stately funeral was organised, with the coffin being borne on a gun carriage through the International Settlement and, no doubt, it was attended by Bessie and Albert. Immediately afterwards, they, together with Jeannie and her two children, boarded the Messageries Maritimes Steamer, Anadyr and sailed for England.[3] Their journey took them through the Suez Canal to Marseilles, across France by train and thence to England. According to the passenger list, Bessie and Albert were accompanied by their amah, who will have shouldered the main work-load – she is unidentified but may have been called Li Ma (a name which appears in an earlier letter).[4] However, with Jeannie and her two boys in deep mourning, it will have been a melancholy voyage.

Arriving in May, Bessie and Albert must have been keen to meet their respective families and show off the children. Whilst there will have been plenty of excitement, there was also sadness. Having returned to England, George Pirkis had recently lost his wife, Susan Maria (née Lyne), shortly after childbirth, leaving him with two children to care for. Of the photographs which can be specifically attributed to the Pirkis’s time in London, the one taken of the children with their amah – fig. 3 – is particularly evocative.

3. Georgie and Amy Pirkis with their amah- un-named, but, possibly, Li Ma. Photographer, H. Daubray, 90, Westbourne Grove, London. Taken when the family was in London in 1878/1879, HPC PF-s0001

Unusual as it was for an amah to be included in a studio portrait, although she is not looking at the camera and may not have welcomed the attention, it indicates that she had built up a close relationship with Amy and Georgie and no doubt also with Bessie and Albert. Little is known about amahs when they came to England and it must have been an extraordinary and somewhat alarming experience for her to have been in London, given that she probably had no opportunity to meet any other Chinese-speaking people during this time. [5]

4. Bessie Pirkis. Studio portrait by Daubray,1878/1879. HPC PF-s0043. This has a different back to the photograph at fig 3. and must have been taken on another occasion. The two cartes no doubt found their way into many other similar collections.[6]

Refreshed after their year away, Bessie and Albert returned to China, leaving via Southampton and arriving in Shanghai on 27 May 1879. Although the amah is not mentioned in the passenger list, it was not unusual for ‘native servants’ to be omitted and she almost definitely accompanied them. On reaching Peking, they found that considerable changes had taken place. As a career diplomat, Hugh Fraser had only been due a short stint in China and, somewhat to the relief of his wife, Mary, they had left. He was succeeded as the

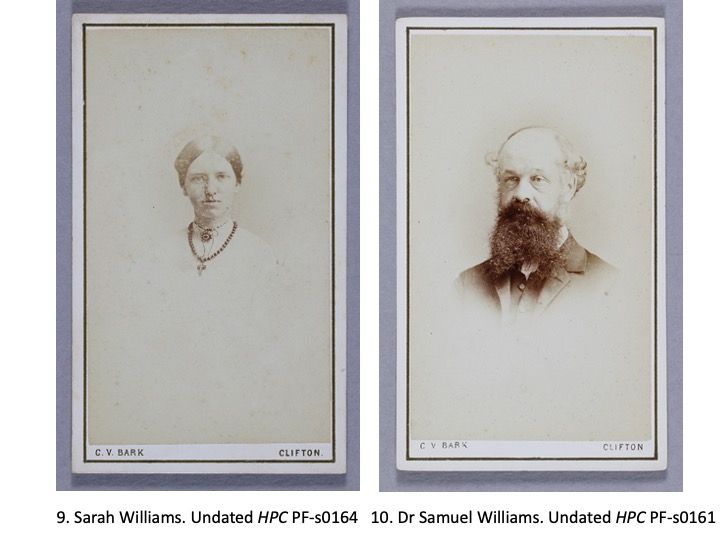

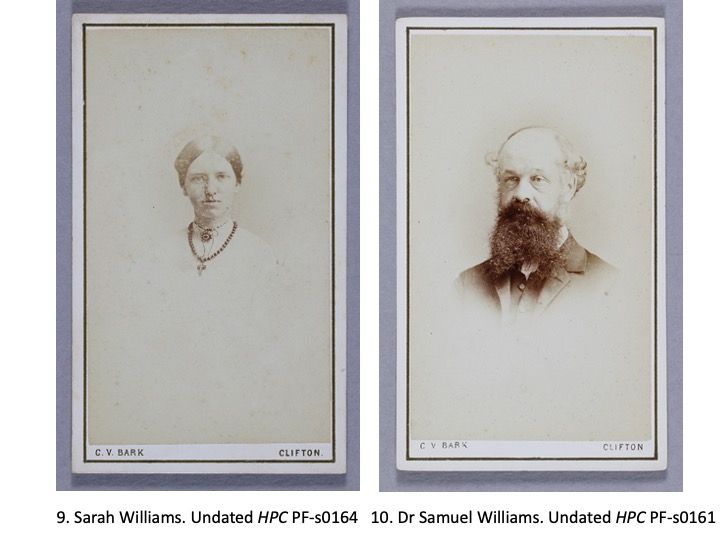

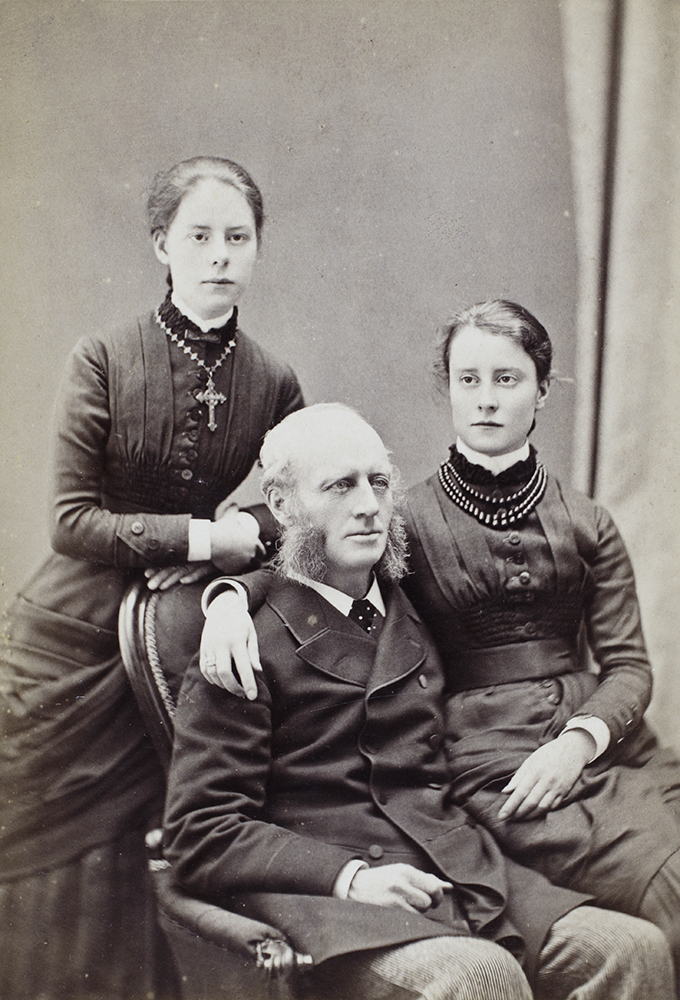

Chargé d’Affaires by the Honourable Thomas George Grosvenor, who had been in Peking since the early 1870s. At some point, he met and then became engaged to Sophia Gardner Williams, the daughter of a medical missionary and Sinologue, Dr Samuel Wells Williams, and his wife, Sarah Simonds Williams (née Walworth). Samuel Williams had been in China since the early 1830s and in 1855 had been appointed the first Secretary of the United States Legation to China. Bessie and Sophia may have first met soon after Bessie’s arrival in Peking, but Sophia’s

carte is dated 1876, and so was given shortly before she left for America. The wedding took place in Connecticut in April 1877, and this was possibly a parting gift before she returned as Sophia Grosvenor.

5. Sophia Williams , on the reverse of the photograph, it is inscribed ‘Mrs Pirkis with love from Sophia Williams 1876’. HPC PF-s0155

Soon after her return, she gave Bessie this picture, taken on her wedding day.

6. Sophia Grosvenor on her wedding day, 24 April 1877. HPC PF-s0793

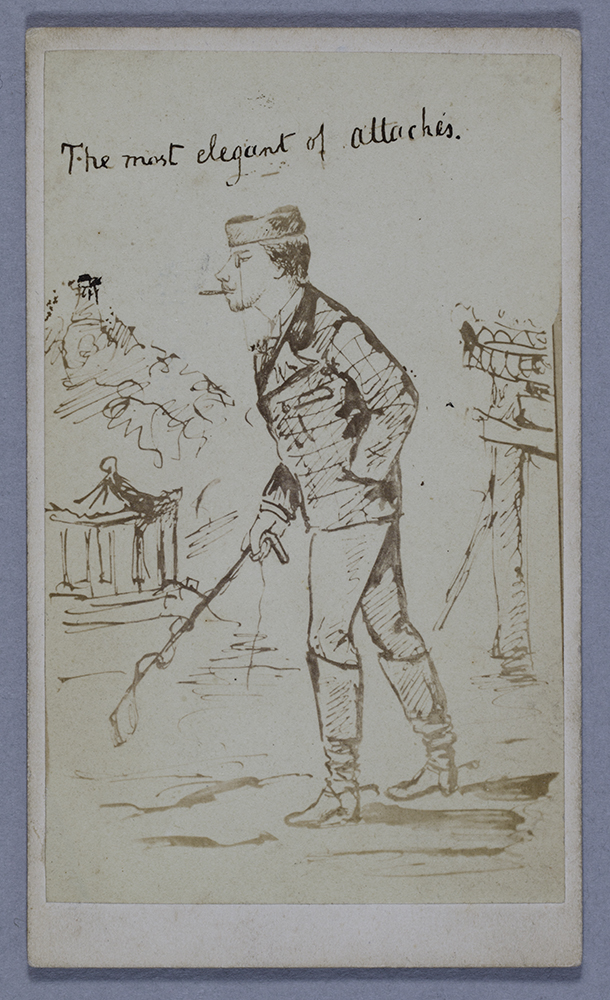

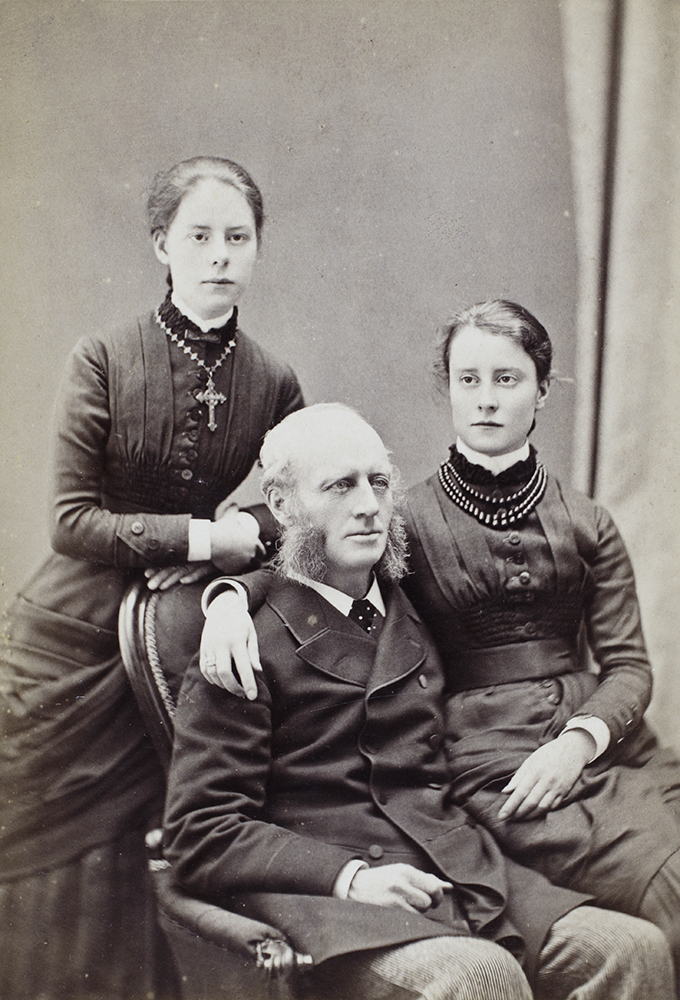

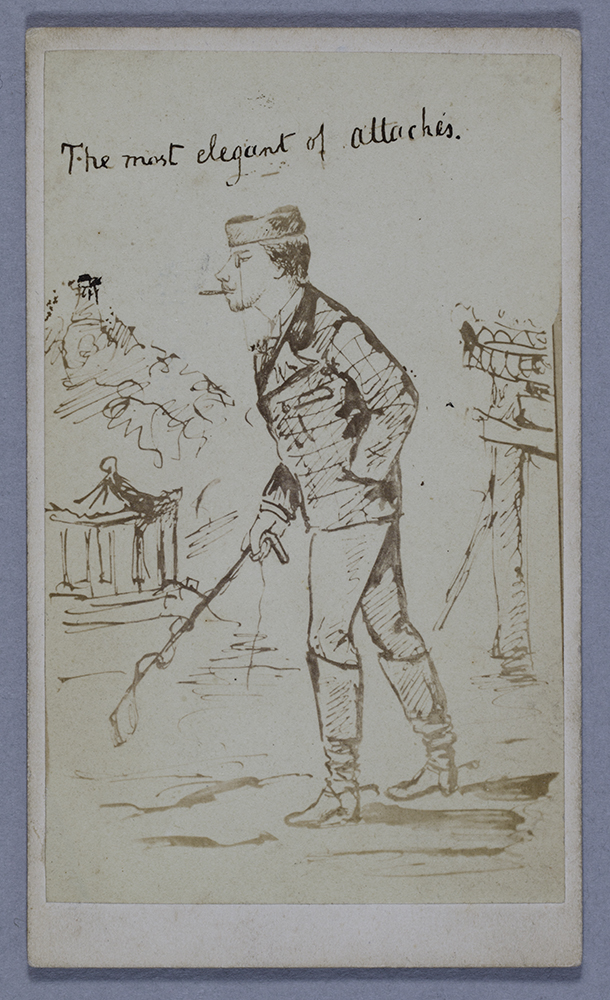

With their immense wealth, deriving in part from London’s Grosvenor Estate, and having no children, the Grosvenors enjoyed a lifestyle very different from that to which the consular staff were normally accustomed. And it was not only wealth which set them apart. ‘Elegance and position’ were also key attributes in the diplomatic world, as Mary Fraser’s memoirs make clear, and, coming from modest backgrounds, Bessie and Albert might have found it difficult to adjust to their world.[7] However, Sophia’s family was deeply religious and this may well have been a strong bond between her and Bessie. It seems clear that the two couples got on well, with Thomas having been made godfather to Georgie. The humorous sketch by Bessie – see figure 7- is most probably of Grosvenor but it could be of Edward Malet, who was Chinese Secretary from 1871 to 1873, and, as is clear from his later letters, also a dear friend of Bessie. [8]

7. ‘The most elegant of attachés’. Sketch probably by Bessie Pirkis, photographed by Thomas Child, of Thomas Grosvenor soon after his arrival at the Legation alternatively of Edward Malet, Chinese Secretary, 1871 to 1873. Undated. HPC PF-s0016

8. Thomas Grosvenor. Undated HPC PF-s0158

In addition to the Williams family, Bessie enjoyed good relationships with the staff from other legations. The Dutch Minister, Jan Helenus Ferguson and his son, Constant, gave her cartes bearing the following inscriptions:

To A.E. Pirkis Esq. With kind regards and best wishes for the welfare of himself and his dear family 9th April 1880

Remembrance from Constant Ferguson to his dear kind friend, Mrs A.E. Pirkis, 9 April 1880.

11.Jan Helenus Ferguson, Dutch Minister. 1880 HPC PF-s0739

12. His son, J.C. Helenus Ferguson (aged 13 years). 1880. HPC PF-s0757

Whether Ferguson’s wife, Maria Eleanor (née Waymouth) was with her husband in Peking is unclear, but certainly they will not have had all thirteen of their children with them.[9] Albert Edwin von Seckendorff, who was attached to the German Legation in the early 1880s, was another friend – see figure 13; in a later letter to Bessie, he talks about the many days he spent with them in Peking.

13. Carte inscribed, “Mr and Mrs Pirkis, as remembrance from their friend, Albert Baron von Seckendorff 28.9.1882”; possibly given on his departure for Tianjin to take up his appointment as vice-consul. HPC PF-s0128.

By the time of the Pirkis’s return from England, Wade was tiring of life in China and wished to spend more time with his books and his family. Although he would formally retire only two years later, in figure 14, we see him shortly before he left Peking, placing himself somewhat unassumingly in the back row and to the side.

14. Consular staff and interpreters. Wade is standing second from the left. Walter Hillier is seated second from left and Pirkis is seated on the far right. C. 1879/1880. Hi-s023. A copy is also in the Pirkis Collection HPC PF-s1018

Following Wade’s departure, Grosvenor took over as Chargé d’Affaires, pending the arrival of Harry Parkes as the new Minister. With his easy-going approach, this was a convivial time and may well have been when the photograph in figure 15 was taken, showing Albert relaxing with the Student Interpreters.

15. Uncaptioned and undated but this would seem to be a photograph of the Student Interpreters with Pirkis reclining beside the ever-present dog. PF-s0630.

Although they would not leave for another twelve months, in October 1882, the Grosvenors held their farewell dinner, an evening which Hart described as ‘the brightest, best, gayest, and pleasantest … we have ever yet had at the British Legation’. [10] The following year, Walter Hillier (elder brother of Harry, who had played with Bessie at Hart’s musical evenings) returned to the legation as Chinese Secretary with his wife, Clare and in July, 1883, they added another baby, Florrie, to the crop of legation children. Extrovert and vivacious, Clare was soon at the heart of legation life, and getting on well with Bessie and Albert who already knew Walter well from his earlier days in Peking.[11]

A keen Sinologist, like Mayers, Hillier was a demanding teacher but he had a lighter side. At some point, he gave the Pirkis’s a photograph of himself as Mother Goose – see figure 16- knowing how much they both enjoyed Amateur Dramatics, which was also a popular aspect of Legation life. Bessie and Clare Hillier both appeared in the Legation’s Christmas play in 1884, an evening which the Minister, Harry Parkes, much enjoyed, as he told his daughter, Marion:

It was a great success; Mrs Pirkis played to great perfection. She got herself up as a most attractive young girl and looked so pretty and acted ravishingly well. Mrs Hillier also did excellently but her part was a more staid one. After the performance the whole house which was crowded came over to me to dance and to sup as last year.[12]

16. Walter Hillier as Mother Goose; inscribed on the back, ‘Canton, 21.1.74’. HPC PF-s0022.

Bessie seems to have been one of the few who were able to get on with Parkes on a personal level. Having lost his wife, Fanny, in 1879, he was extremely dependent on his two daughters, Marion (‘Minnie’) and Mabel, both of whom came with him to Peking. The earnest tone he introduced is palpable in the carte in figure 17 – one of the last photographs to be taken of him – which will have been duly presented to Bessie soon after their arrival.

17. Mabel Desborough Parkes (later Levett), Marion (Minnie) Parkes (later Keswick) and Sir Harry Parkes. Undated. HPC PF-s0786

A year later, in October 1884, Minnie married James Keswick, a partner in Jardines, and left for Shanghai. Parkes was bereft, as he told his daughter, ‘We have had no events of any kind and I am afraid the Legation is much duller than before’.[13] Not known for relaxation or conviviality, he drove himself as hard as he drove his staff, and six months later he was dead. However, Bessie seems to have established reasonably good relations with the two Parkes sisters and, despite their father’s gloomy account, continued to enjoy herself. [14]

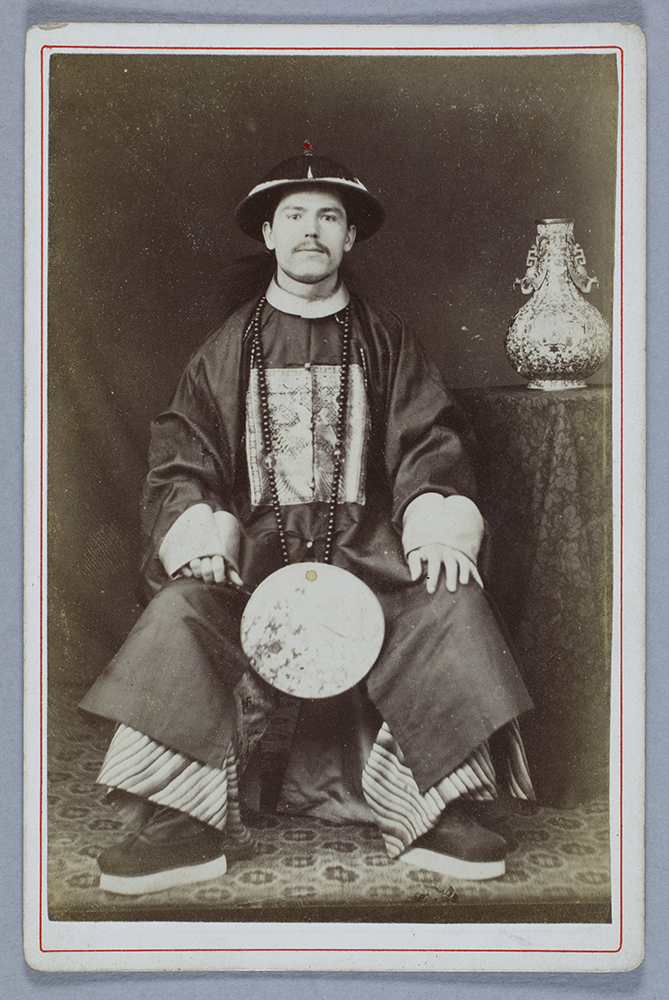

Music was her real passion. She had performed professionally before coming out to China and, having published some songs, she helped Hart with his own compositions, with a view, to producing, he told Campbell, ‘ten songs, ten drawing-room pieces and perhaps ten sonatas …’.[15] Also taking part in Hart’s musical evenings was J.A. van Aalst, a Belgian, who had arrived in Peking in January 1883 having been appointed Postal Clerk.[16] An extremely junior position, it is nonetheless clear that Hart was keen to support this young man because, as he told Campbell, ‘he had made his way up from nothing’ and, more important, was ‘a fine musician’,

With him on the flute, Mrs Pirkis at Piano, Scherzer at harmonium, Lyall on violin and myself on ‘cello, we have considerable music every Saturday evening.[17]

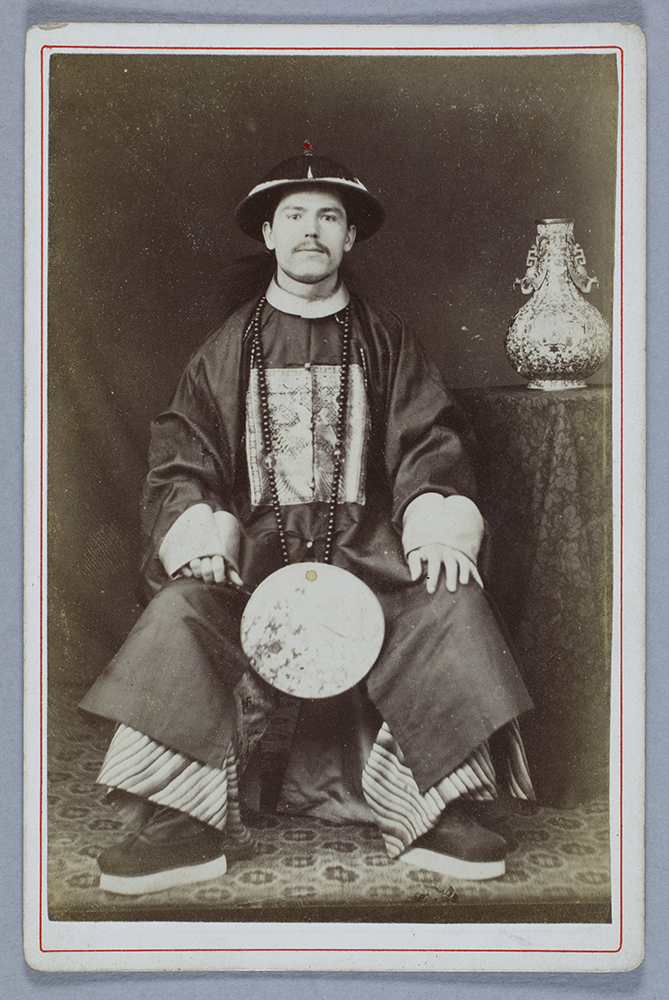

Despatching van Aalst to England the following year to deliver lectures on Chinese music during the Fisheries Exhibition, Hart warned Campbell that he was inclined to be ‘morose and bad-tempered’, a prediction which turned out to be all too well-founded, when Campbell had to be retrained from dismissing him because of his arrogant behaviour. [18] However, picking up his music when he returned to Peking, van Aalst made friends with Bessie and presented her with the carte at figure 18.

18. Inscribed on the reverse ‘J.A. van Aalst, Peking, 29 April 1885’. PF-s0703.

Given what we know about him, it is perhaps not surprising that he chose to be photographed looking somewhat arrogant in the robes of a Chinese official. If this was principally to show those at home that he had truly ‘arrived’, as we see from the accompanying letter to Bessie, it had a different purpose. Albert’s health was failing and the Pirkis’s were already packing up to return to England for a period of recuperation. Enclosing the scores of two songs, “Sublime Lesson” and “Goodbye, dear friend”, van Aalst told Bessie that the latter composition, made up from various verses he had found, was offered as a ‘souvenir’ and a ‘tribute of [his] esteem and respect’.[19]

Four weeks later, Albert and Bessie sailed for home with the children. It is clear from their letters that this was an anxious time and Amy and Georgie were sent to stay with cousins, whilst Albert searched for a cure. Sadly, he had left it too late and died on 7 July just one month after their arrival. The news will have come as a terrible shock for those who had known him so well in Peking, for, as the North China Herald observed, ‘a kinder or more genial man, there never was’.[20] Bessie would live on for another fifteen years, bringing up the two children and surrounded by mementoes of their years in China, including her paintings and, of course, her photographs. She and Albert were buried side by side in Kensal Green Cemetery, with Albert’s head-stone bearing a Chinese character meaning ‘love’– see fig. 19.

19. Kensal Green Cemetery. The gravestones of Albert (on the left) and Bessie Pirkis, 2023. Courtesy, Nicola Pirkis. With the Chinese inscription, Britain in China was transposed into a London cemetery.

If the dominant image of Legation and Consular life in China is that of patriarchal figures, heavily bearded, with the women in the shadows, the photographs in the Pirkis Collection provide a very different picture. Whilst only a few can be included in this blog, taken together they show that Bessie had a wide range of friends both inside and beyond the legation. Although often over-looked, this sort of intimacy underpinned Legation life, softening its edges and humanising it. This was important for all those engaged in that world, not least the Student Interpreters, who, away from home for the first time and struggling to learn Chinese, were still highly impressionable. The presence of women and children was key to creating a familial atmosphere in what was otherwise an unfamiliar world and Bessie played an important part in that process, as well as being at the centre of legation life. Cartes could be exchanged not only as tokens of affection but also to keep alive the memory of those friendships, when lengthy separations were about to take place. They could also help to maintain links between Peking and Europe – we can, for example, imagine van Aalst’s family, proudly showing his portrait to their friends and relations at home.

For the legation children, this was also a formative stage in their lives. Save for the year they spent in London, Amy and Georgie had known only the legation world. Returning to England, aged thirteen and ten, they would maintain contact with many of those they had known and pass on their memories of those years to the next generation, no doubt, drawing on these photographs to remind them of this world.[21]

——

Andrew Hillier’s The Alcock Album: Scenes of China Consular Life, 1843-1853, will be published by City University Press, Hong Kong, later this year. Click here for more details and updates.

[1] The surviving individual images of Bessie and Albert measure 18 x 16.5 cms and are slightly different from those in the photograph. This could indicate that in some cases Bessie made a number of copies. It is also possible that one set of originals was retained together as we see in the photograph.

[2] Bickers, Robert, The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914 (London: Allen Lane, 2011), pp. 266 and 268-9; https://hpcbristol.net/collections/henderson-david-marr.

[3] North China Herald, 28 March 1878, p.322.

[4] Li Ma’s name appears in a letter from Sophia Grosvenor to Bessie, dated 11 June, which must have been written in 1883, since it refers to the Hilliers, who had only arrived earlier that year – by then, Walter’s wife, Clare, was seven months pregnant. It appears Bessie was on holiday in Yokohama at the time. There is also mention in the same letter of Shing-erh, who may have been Li Ma’s daughter, in which case, it would show how much amahs were part of the family.

[5] Cf. https://ayahsandamahs.com/

[6] See also a photograph of Albert taken by the London Photographic Company during this trip, PF-s0034.

[7] Cf. Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), p.13

[8] For similar use of the term, see A.B. Freeman-Mitford, The Attaché at Peking (London: Macmillan and Co., 1900), a volume of letters written by a young diplomat whilst serving in the legation in the mid-1860s.

[9] Married in 1859, when she was aged fifteen, Maria died aged 46.

[10] Letter, Hart to Campbell, 6 October 1882, no. 379, John K. Fairbank, Katherine Frost Bruner, Elizabeth Macleod Matheson (eds), The I.G. in Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs, 1868-1907 (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1975).

[11] See fig.4 in Part 1. and Andrew Hillier, Mediating Empire: An English Family in China, 1817-1927 (Folkestone: Renaissance Books, 2020), pp. 120-129 and 199-201.

[12] Undated letter, Stanley Lane-Poole, The Life of Sir Harry Parkes, Sometime Her Majesty’s Minister to China & Japan (London: Macmillan, 1894), vol.2, p.421; see also a review of a later play in North China Herald, 18 March 1885, p.313.

[13] Letter, November 1884, Lane-Poole, Harry Parkes, II, p.416. Hart’s wife, Hester, and their three children were back in England.

[14] Lane-Poole, Harry Parkes, II, pp. 415 and 426-7.

[15] Letter, Hart to Campbell, 21 January 1884, 460; see also, 10 June 1884, 484, Fairbank, The I.G. in Peking.

[16] Born in 1858, according to the CMC Service List, 1881, he joined the Customs that year although his official service record gives the date of his first appointment as 1 April 1883, https://www.chinafamilies.net/customs_service/5707-aalst-j-a-van/ . Certainly, he was in Peking by January 1883; see letter, Hart to Campbell, 7 January 1883, 395, Fairbank, The I.G. in Peking.

[17] Letter, Hart to Campbell, 11 August 1883, no. 429, Fairbank, The I.G. in Peking.

[18] See letters, Hart to Campbell, 14 January 1884, 458, 23 March 1884, 470 (for the quote), 21 June 1884, 487 and 5 December 1884, 507, Fairbank, The I.G. in Peking.

[19] Letter, van Aalst to Bessie Pirkis, 29 April 1885 (Private Collection). Although he was promoted, he continued to have a chequered career and ‘ran off the lines’, having to be replaced as Postal Secretary (see letter Hart to Campbell, 12 October 1901, 1218, and later, 9 July 1905, 1382, Fairbank, The I.G. in Peking), but rose to the rank of Commissioner and retired in 1914. He became the leading authority on Chinese music, publishing a learned treatise on it- see Han Kuo-huang, ‘J. A. Van Aalst and His Chinese Music’, Asian Music ,19 (1988), pp. 127-130. For two photographs of him with his wife in Xiamen in 1904, see Queens University, Belfast Special Collections, MS 15.6.2A.076 and 077, https://www.flickr.com/photos/qubspecialcollections/19729190409/in/album-72157653886629503/ https://www.flickr.com/photos/qubspecialcollections/19942386305/in/album-72157653886629503/

[20] NCH, 28 August 1885. The news seems to have taken longer to reach Peking and a poignant note is struck by a letter from Hart written on 29 August asking Campbell to forward to Bessie a parcel containing a small violin which he had procured for Georgie; letter, 29 August 1885, 536.

[21] Amy would never marry and it is possible that it was who captioned the photographs, a way of treasuring the memory of those years.