Dr Helena F. S. Lopes is Senior Research Associate in the History of Hong Kong and a Lecturer in Modern Chinese History at the University of Bristol. She holds a DPhil in History from the University of Oxford.

Wikipedia’s ‘List of statues of Queen Victoria’ includes more than a hundred such monuments scattered around the world, many of them in former British colonies. One remains in Hong Kong, having endured more than a century of tribulations.

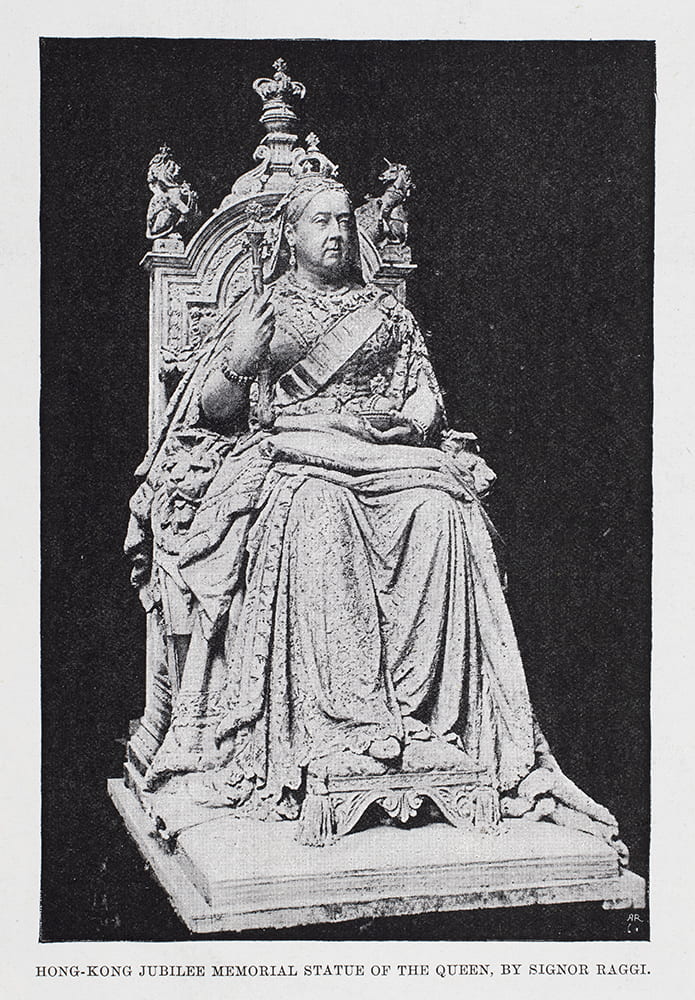

Commissioned by the Hong Kong Jubilee Committee to mark the fiftieth anniversary in 1887 of Queen Victoria’s accession, the statue was funded by public subscription and designed by the Italian sculptor Mario Raggi (1879-1907), who lived and worked in London. Amongst his notable works were other memorial statues, including one of Benjamin Disraeli in Parliament Square (1883) and one of William Gladstone in Albert Square, Manchester (1901). Raggi’s statue of Queen Victoria was cast by H. Young and Co., bronze statue founders in Pimlico, a company which had been responsible for other prominent sculptures in the capital such as the monument to the Duke of Wellington in St Paul’s Cathedral.

Statue of Queen Victoria, designed by Mario Raggi, for Hong Kong. ‘The Illustrated London News’, 28 January 1893. HPC ref: Bk13-04.

In 1893, before being shipped to Hong Kong, Queen Victoria’s statue was exhibited in London. The Illustrated London News reported on the viewing and included a photograph of the sculpture without the canopy that would be attached to it in Hong Kong. In the article, the vision of the statue’s commissioners is described as one of British colonial loyalty. The ‘artistic memorial’ was to be ‘fixed upon a prominent site in Hong-Kong, as a mark of the loyalty of that colony to the Queen and of their attachment to the mother country’.[i]

The ‘prominent site’ selected was on Wardley Street, in the heart of what was then known as the city of Victoria, on a site on the newly-reclaimed waterfront. Still, it would be almost ten years until the statue was finally unveiled on 28 May 1896, on the occasion of celebrations for the Queen’s 77th birthday. A few weeks before the event, the North-China Herald reported on a committee meeting debating the unveiling ceremony to be presided by the Governor, Sir William Robinson. It stipulated that ‘it should be made as public as possible, all foreign Consuls, all officers of the Army and Navy, and all subscribers of the Fund being invited, as well as all the ladies.’ Efforts would also be made for ‘having as grand a military display as possible.’[ii] This performance of colonial might was projected as an elite affair, even though afterwards the statue was on full display for anyone passing through the square.

Even in its early days, the statue caused some controversy. Shortly after the unveiling ceremony, the Hong Kong Daily Press lamented that the ‘predominant feeling with reference to the Queen’s statue is one of disappointment’. This was due to the materials used: ‘Bronze under a canopy is an anomaly and is repulsive alike to common sense and artistic feeling’. Citing a 1890 letter from James Johnstone Keswick, the Scottish businessman who had been the Chairman of the Queen’s Jubilee Memorial Committee in Hong Kong, the article noted that there had been a misunderstanding with the sculptor regarding which material to use and a decision in favour of marble had been lost in communication. The idea of requesting a marble replacement was considered but it did not occur.[iii] In her study of Sir Catchick Paul Chater and Statue Square, Liz Chater mentions that a small marble statue of Queen Victoria was also cast in the same period, most likely for a private client (her book includes a rare photograph of it).[iv]

Queen Victoria’s Statue, The Cenotaph and the Hong Kong Club, Statue Square, Hong Kong, c.1924. HPC ref: Bk09-11.

The Historical Photographs of China website has some images of what is now known as Statue Square, where Queen Victoria’s monument first stood. A few, likely taken in the 1920s, are in an album (ref: JC01) in the Jamie Carstairs Collection. The statues are not the main focus of the unknown photographer, whose views over the square tend to privilege iconic buildings such as the Supreme Court (which later housed the Legislative Council and now the Court of Final Appeal). Queen Victoria can be glimpsed in some of these. A slightly closer look at the sculpture can be found in the photographs by Denis H. Hazell published in his Picturesque Hongkong.

Despite its controversial bronze-marble combination, the statue of Queen Victoria became a major landmark in the city. It was regularly featured in photographic albums such as JC01, illustrated books such as Hazell’s and tourist guidebooks such as that written by R. C. Hurley and published in 1897 – only one year after its unveiling. In June 1911, to celebrate the coronation of George V and his wife Mary, the statue was decorated with dozens of Chinese lanterns on wires – a nocturnal spectacle captured with stunning results by the Lai Afong (賴阿芳) Studio, ran by one of Hong Kong’s most distinguished first professional photographers.

Queen Victoria’s statue, Hong Kong, lit up with lanterns for the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary, June 1911. Photograph by Afong Studio (Lai Fong). HPC ref: Bi-s184.

Victoria’s image in Hong Kong was not just that of a visual symbol of colonial prestige. Its materiality as a valuable bronze statue was to be of no small importance. During the Pacific War, when Hong Kong fell under Japanese occupation, the statue was taken to Japan to be melted down and the metal recycled for the Japanese effort. The wartime dismantling of the statue mirrors what happened elsewhere, notably in Shanghai where memorials erected by foreign communities, such as the statue of Sir Robert Hart or the Allied War Memorial, were taken down. In Shanghai, and despite attempts to the contrary, these statues were not reinstated after the war, their absence a signifier of de facto decolonisation.[v] In Hong Kong, colonial rule returned and so did Queen Victoria.

The statue of Queen Victoria, damaged during the war. Source: Bill Hillman “Hillman WWII Scrapbook, HMCS Prince Robert Tribute Site”.

Some of the other monuments in Statue Square did not escape their intended wartime fate. But Victoria survived the ordeal, despite some damage, and was returned to Hong Kong after the war. The restored version – without the canopy – was unveiled in 1952 in Victoria Park, where it continues to stand today.

Statue of Queen Victoria in Victoria Park, facing south in the tradition of all Chinese Imperial figures, November 2008. Photograph by Minghong. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The statue’s association with the British empire – a considerable expansion of which happened under Victoria’s long reign – has become for some a contested symbol in late- and post-colonial Hong Kong. In 1996, about a year before the Hong Kong’s handover, Pun Sing Lui (Pan Xing Lei 潘星磊), a twenty-something artist, defaced the statue with red pain and broke its nose, protesting against ‘dull, colonial culture’.[vi] Pun was arrested and the statue fixed. For some, it remains an uncomfortable monument, as news of a possible ‘cover up’ in the running up to a visit by President Xi Jinping in 2017 suggest.[vii] However, its public display at Victoria Park has seen other types of protest, too. Over the past months, it has been a site where pro-democracy protesters gathered, their numbers and movement dwarfing the static Victoria.[viii] Some also chose to make her a vehicle for their message.

The many lives of Queen Victoria’s statue and its multiple meanings have recently inspired a solo exhibition by the Hong Kong artist Lee Kai Chung (李繼忠). Entitled ‘I could not recall how I got here’ (「無法憶起我怎樣到達這裏」), and awarded the WYNG Media Award in 2018, the show was based on archival research about the history of the statues seized by Japanese forces. The artist uses photography, film, bronze sculpture, 3D modelling, and 3D printing to investigate ‘the transition of meanings of a “memorial bronze statue” brought about by the passing of time’.[ix] As this latest artistic reinvention of the statue shows, both its symbolism and the material aspects of its production and reconstruction continue to invite multiple interpretations.

Notes:

[i] ‘Signor Raggi’s Statue of the Queen’, The Illustrated London News, 28 January 1893, p. 118.

[ii] ‘The Queen’s Statue in Hongkong’, The North-China Herald, 8 May 1896.

[iii] ‘The Queen’s Statue: Why is it in Bronze instead of Marble’, The Hong Kong Daily Press, 30 May 1896.

[iv] Liz Chater, The Statues of Statue Square, Hong Kong (Chater Genealogy Publishing, 2009), pp. 15-16.

[v] On these, see Robert Bickers, ‘Moving Stories: Memorialisation and its Legacies in Treaty Port China’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42/5 (2014), pp. 826-856, Robert Bickers, ‘Lost monuments and memorials of the Shanghai Bund 1: The War Memorial (1924)’ and ‘Lost monuments and memorials of the Shanghai Bund 2: Statue of Sir Robert Hart, 1914’.

[vi] The episode is analysed in Elizabeth Ho, Neo-Victorianism and the Memory of Empire (London: Continuum, 2012), pp. 1-6.

[vii] Danny Mok and Tony Cheung, ‘Out of sight, out of mind? Queen Victoria statue obscured by boards and banner ahead of Xi visit’, South China Morning Post, 28 June 2017.

[viii] E.g. ‘Hong Kong: 1.7m people defy police to march in pouring rain’, The Guardian, 18 August, 2019; ‘China condemns U.S. lawmakers’ support for Hong Kong protests’, The Asahi Shimbun, 18 August, 2019.

[ix] ‘LEE Kai Chung Solo Exhibition, ‘I could not recall how I got here’, WMA Commission.