Paul French, the author of this guest blog, lived and worked in Shanghai for many years. French’s 2018 book ‘City of Devils’ was his much-anticipated second literary non-fiction book and was a Kirkus Book of the Year. Devils followed ‘Midnight in Peking’, which was a New York Times Best Seller. He recently published a collection of his writing, ‘Destination Shanghai’ – eighteen tales of old Shanghailanders, famous, infamous & previously forgotten.

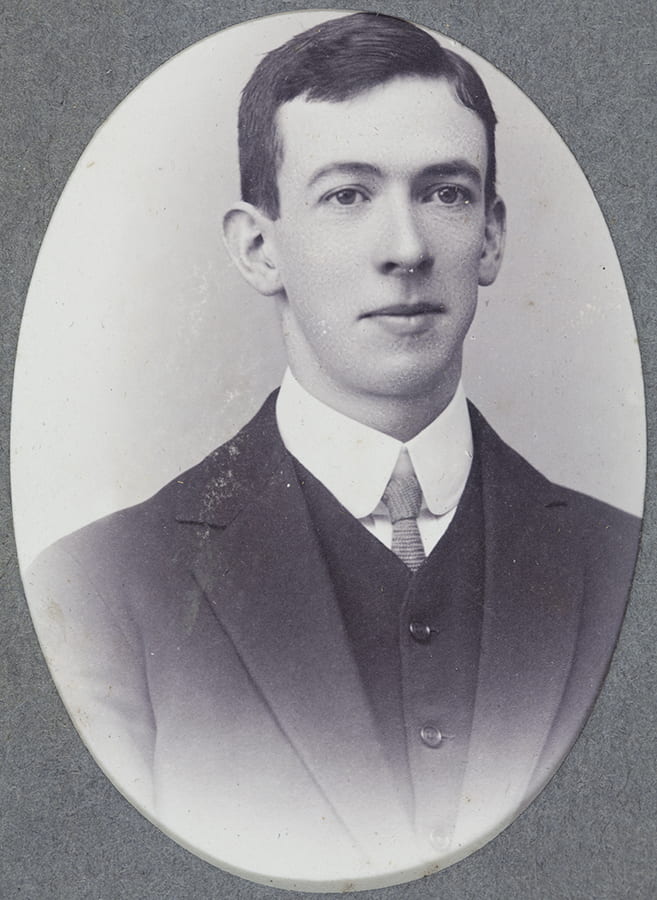

I have written about H.G.W. Woodhead a few times, most expansively in my history of foreign correspondents in China between the Opium Wars and 1949, Through the Looking Glass (Hong Kong University Press, 2009). But I’d never seen a photo of him – now I see that the Historical Photographs of China web site has at least two. So I thought it worthwhile offering up my short biography of Woodhead’s adventures in the Chinese treaty port media in the first half of the twentieth century…

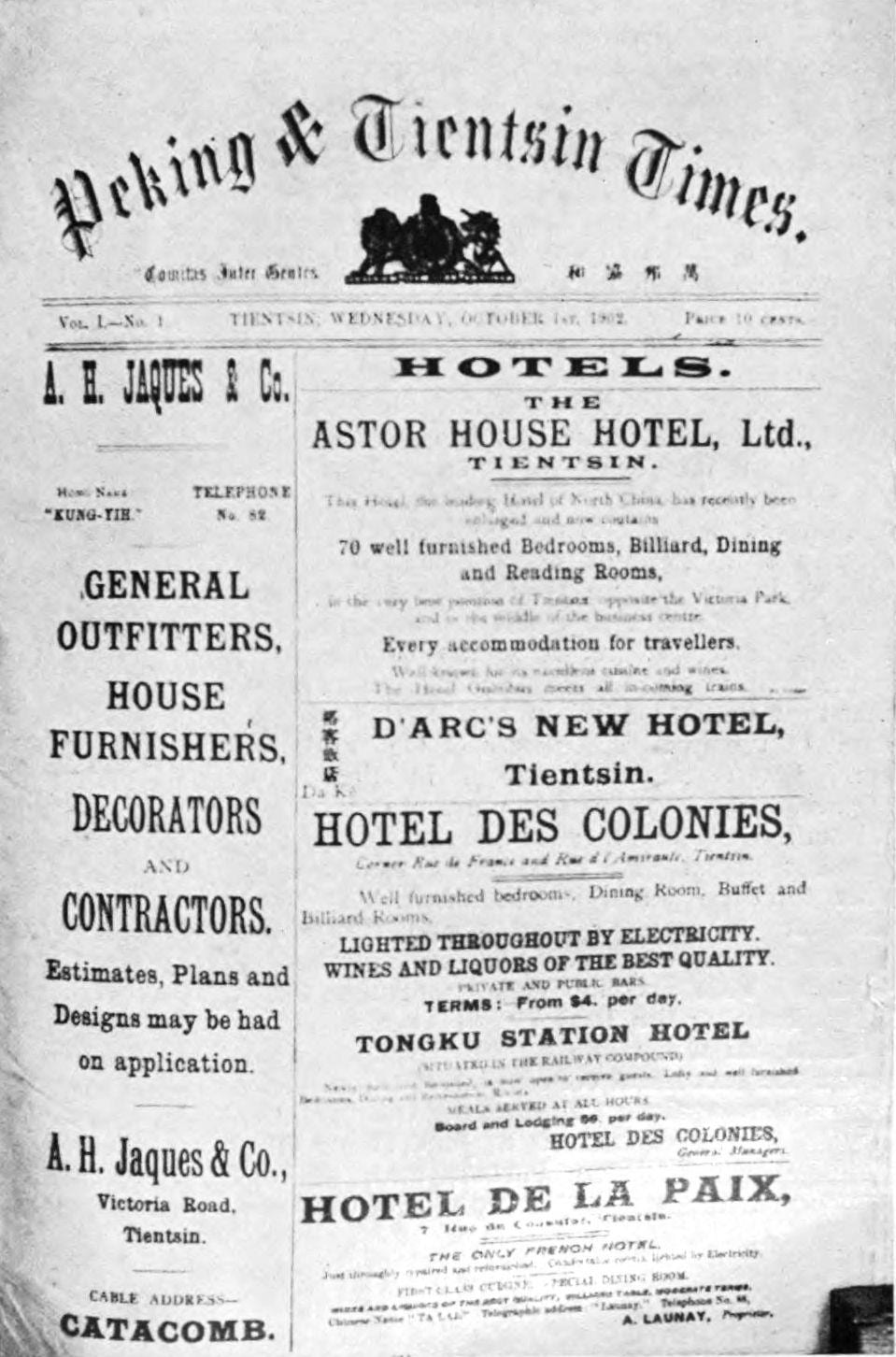

Henry George Wandesforde (“H. G. W.”) Woodhead arrived in China in 1902. He obtained a position as the editor of the Peking Daily News (which included the old Chinese Public Opinion) whose header stated “Impartial But Patriotic” and always started with the latest imperial edicts. Woodhead was to rule the roost at the Peking and Tientsin Times as well as becoming the most well-known and influential foreigner in Tianjin for several decades.

The paper invariably reflected his strident opinions on China and the world and from the start promised to “… be essentially British”, a virtue Woodhead staunchly upheld. Much later, in 1936, Time magazine described him as “hard hitting” and “suave”, though J.B. Powell’s China Weekly Review opted for “die-hard”, which was not meant in an overly complimentary way. Woodhead was a long-time friend of former London Times war correspondent Henry Thurburn Montague Bell, who had covered the Boer War and then became a long-standing editor of the North China Herald and the North- China Daily News. He was also a prolific editorialist, was well known as a China Hand in Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin and wrote the 1929 book Extraterritoriality In China: The Case Against Abolition, which was really just a collection of his articles expressing his trenchant views on the subject from the paper. This title also pretty much summed up Woodhead’s political attitude to both China and the Chinese which accounted for the uncomplimentary opinions of people like Powell who were anti-extraterritoriality. H. T. Montague Bell was also well connected in London due to his being the brother-in-law of the editor-in-chief of the Times.

In the 1920s Woodhead launched a campaign to try to stop Britain from spending its Boxer Indemnity monies (the reparations forcibly paid by the Chinese government to Britain and other foreign powers after the Siege of the Legations) on promoting education in China as he believed that the schools and colleges of the country were little more than breeding grounds for revolutionaries and anti-foreign, anti-extraterritoriality sentiment. When it was reported that a Chinese mob had stormed the British Concession in Hankou and that the British government had seemingly caved in and handed the territory back to China, Woodhead fumed that “The principle of extraterritoriality is at stake” and urged Britain to remember the Treaty of Tianjin that guaranteed the treaty ports system and to oppose the government. On another occasion, he declared that Britain should have conquered China rather than India in order to ensure the country was well run. He regularly fulminated against America for its “Open Door” trade policy towards China which, he believed, would undermine Britain’s “Most Favoured Nation” status — a status it has to be said which had been forced at gunpoint on the Chinese. Brian Power, a young boy in Tianjin at the time recalled in his memoir Ford of Heaven: “When Woodhead spoke Washington trembled … By the time Woodhead’s outbursts reached England, Whitehall, too, must have trembled”.

This was probably overestimating Woodhead’s influence somewhat but, on the other hand, he was equally tough in criticising many foreign businessmen, accusing them of becoming wealthy off the back of child labour and low wages. He also had a major influence on Tianjin’s civic life. He had urged the formation of the Watch Committee, an ad hoc group that sought to patrol and protect the foreign concessions, and he was a founding member of the Tientsin Club, which provided him with a lavish send-off dinner when he finally left the city.

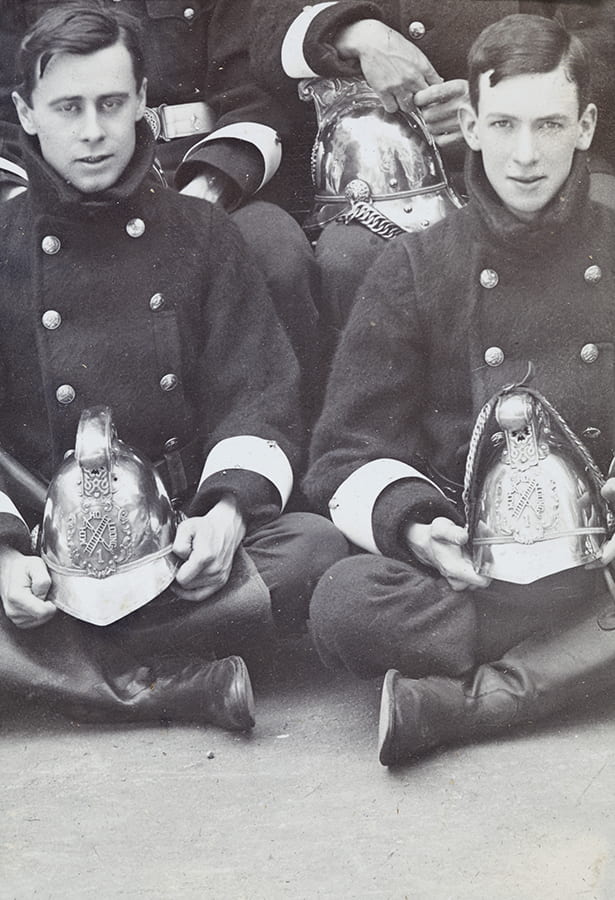

George Woodhead (on the right), with other fire brigade volunteers, Mih Ho Loong Hook and Ladder Company Number 1, Shanghai, c.1902-1907. LD01-099.

Woodhead remained a vibrant and dedicated editorialist, moving on in the 1930s to be an editorial associate of the Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury and editor (from 1934) of the quarterly journal Oriental Affairs. Power recalled that foreigners in the city were “stunned” when Woodhead announced his departure to Shanghai. Tributes to the great editor, which resembled obituaries, poured into the paper. Power believed that, despite his “Bully Pulpit-style” of editorialising, Woodhead’s lasting impression on Tianjin was his defence of the rights of car drivers. He accused the Chinese of being “primitive” for opposing the rise of the car. It seems that an unresolved incident between Woodhead and a rickshaw puller after a collision was the cause of his repeated diatribes against Chinese car drivers.

Woodhead and the Times did provide work for some young reporters who would later become better known. In 1921 a young Owen Lattimore passed through. His parents were living in Tianjin but were about to move back to America. Lattimore met Woodhead who offered him a job at the paper which the young American accepted as he thought it would give him an opportunity to develop his literary interests. However, he was to be disappointed as he was given few opportunities to investigate and write stories of his own, spending most of his time proofreading. He lasted a year before returning to work for his old employers, the traders Arnhold and Company, on a larger salary and at their Tianjin branch before becoming one of America’s foremost China Hands and experts on Mongolia. After Lattimore, a young Israel “Eppie” Epstein, later to become a senior member of the Communist Party of China and remain in Beijing supporting Mao and the revolution, started his journalistic career on the paper in the 1930s when he was barely 15 years old. Epstein had been born in Poland but his family escaped from the Russian Revolution and fled to Tianjin where he attended American-run schools before becoming a cub reporter.

Woodhead appeared all-powerful in Tianjin between the world wars, though he did have some competition. The North China Commerce newspaper was established in 1920 as an English-run weekly but didn’t last long while the American-owned North China Star was also published in Tianjin. This was real competition – the American State Department estimated the paper’s daily circulation in 1921 as 2,500, more than double Woodhead’s Peking and Tientsin Times, but also noted that the Star was far less influential than Woodhead’s paper which to men like Woodhead was what really counted.

Woodhead appeared all-powerful in Tianjin between the world wars, though he did have some competition. The North China Commerce newspaper was established in 1920 as an English-run weekly but didn’t last long while the American-owned North China Star was also published in Tianjin. This was real competition – the American State Department estimated the paper’s daily circulation in 1921 as 2,500, more than double Woodhead’s Peking and Tientsin Times, but also noted that the Star was far less influential than Woodhead’s paper which to men like Woodhead was what really counted.