While reading journalist Ian Gill’s articles in the South China Morning Post on his search into the history of his China coast family, we were struck by the place of photographs in that story and invited him to tell us more.

Search for My Genealogical Holy Grail

Family lived in treaty ports from end of the Opium Wars till Communist ascent

By Ian Gill

It was a short question, out of the blue, that led to the discovery of my genealogical Holy Grail — photographs of my English great-grandparents and grandparents who had settled in Hong Kong and China from the 1860s.

“Do you know Duncan Clark? He is the grandson of another Duncan Clark who was a tidewaiter with the Customs in Chefoo.”

The query was from Robert Nield, author of two books on China’s treaty ports, and it was as if he had doused me with a bucket of icy water. It awoke a memory of my mother saying her aunt Annie, sister of her father Frank Newman, had married a Scot named Duncan Clark.

Consular records show that, indeed, Anne Elizabeth Victoria Newman, 22, did marry Duncan Clark, 36, at St. Andrew’s Church on Chefoo’s waterfront on April 6, 1893. The couple also made the short trip up nearby Consulate Hill to sign the marriage register at the British Consulate. Annie’s two brothers, Frank and George, also signed the registry, her younger sister Ellen would surely have been maid-of-honour, and a talented singer, James Glassey, no doubt sang in church.

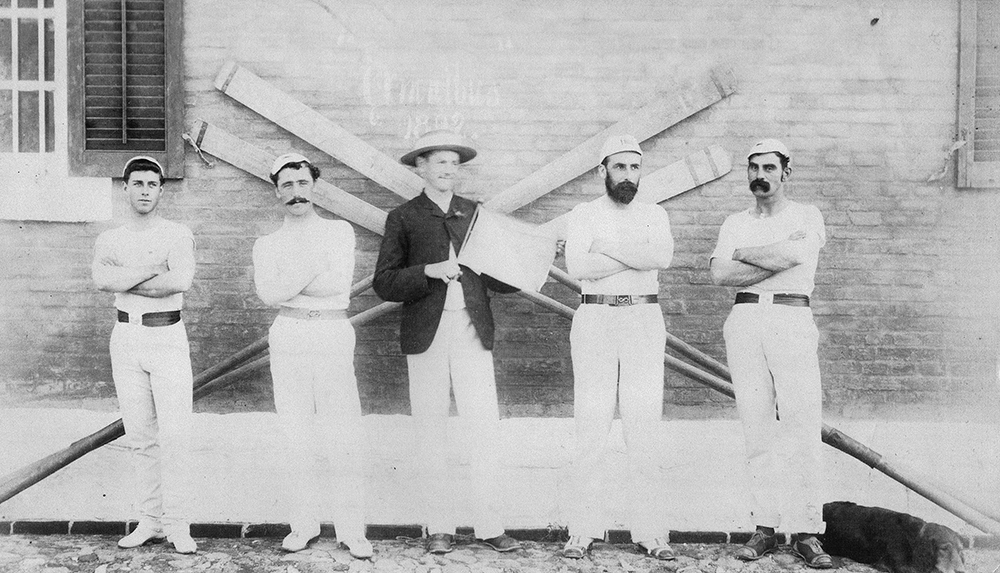

The Newmans in the 1890s. Frank is on the far left, Duncan and Annie Clark are fourth and third from the right. Image courtesy of Graham Clark.

Just over a year later, there were further celebrations under St. Andrew’s picturesque castle-like tower, when Ellen Eliza Maud Newman, 20, tied the knot with James Arthur MacFarlane Glassey, 26, on June 4, 1894. The two marriages cemented ties that already existed between the Newmans, Clark and Glassey. Frank Newman and his new brothers-in-law were colleagues in the Imperial Maritime Customs and the three were also on the customs rowing team. But signs were appearing that these inter-family connections might be loosening. One week after Ellen’s wedding, a notice in the North-China Herald announced that “The Family Hotel”, which had been owned by their late parents, Edward and Mary Ann Newman, was being discontinued as a family enterprise and sold off to a syndicate of buyers.

It wasn’t long after this that the Glasseys and the Clarks left the tiny treaty port of Chefoo. Duncan and Annie moved to Weihaiwei for business opportunities when it became a British territory in 1898. Annie would deliver six children before dying on November 16, 1906, at age 36 of broncho-pneumonia and nephritis, but Duncan would go on to remarry — the governess — have two more children, and make a fortune.

James and Ellen Glassey were transferred to Amoy, he became a customs assistant examiner, and they moved to glamorous Shanghai. They attended George Newman’s wedding to Dorothy Carozzi at Shanghai Cathedral in 1904 but, the following April, James was not listed among the guests at the customs fancy dress ball at which Ellen wore a “Swiss girl” costume. Perhaps he was unwell, for he took unattached leave from the customs and died of blackwater fever or malaria on September 15, 1907, a month shy of his 40th birthday.

Leaving one boy behind at school, Ellen took her younger son Jim to Japan, where she worked as a governess before resettling in America in 1911. Jim found my mother after returning to China after the war and our families have been in touch ever since.

But we lost contact with the large Clark clan — until Robert Nield asked his question while we were discussing Chefoo. The younger Duncan, it transpired, had helped Nield with his research and was living in Coventry, England.

I realized that Duncan might be able to add significantly to the story of my family’s involvement with treaty port China that began when my great-grandfather Edward Newman arrived in Hong Kong around the end of the Opium Wars and ended with my mother being evacuated from Shanghai shortly before the Communist takeover in 1949. Duncan was surprised to receive my call but was cordial and agreed to meet. By coincidence, I was headed to England with my family on a tour of universities and Coventry was on the schedule. I was thrilled at the prospect of meeting my cousin but nervous, too, as I had high hopes but little idea as to how things would turn out.

Up to that point, my conduit with my forebears had been my mother, Louise Mary “Billie” Gill, M.B.E., who died in 2006. As well as being a gifted raconteur with a phenomenal memory, Billie was a scrupulous keeper of family records and mementoes. She had become a Newman by adoption. In Changsha, a few weeks after her birth in 1916, she had been taken in by Frank Newman, Acting Commissioner with the Chinese Post Office, and his Chinese wife, Liu Mei-lan. Marylou, as she was called, joined two daughters: Jessie, 12, and Dorothy (Dolly), also adopted, from Central Asia.

My mother, who was known as Billie for most of her life, had an extraordinary background. Ethnically Chinese, she was raised as a Eurasian — and regarded herself as one – but, in speech and manners, became more British than many Britons.

My mother Billie – from abandoned Chinese baby –

to M.B.E. Photograph by Josepho Shick, Shanghai, courtesy Gill family.

She loved her parents and kept their photographs in silver frames in our living room. One treasured legacy of Mama was the black-and-gold ceremonial jacket she had worn for her wedding. Mama, who in her photograph wears a dark Chinese gown and has flattened hair, was warm-hearted and expressive. She was a devoted mother who, though foot-bound, took Billie as a child to mahjong games and the Chinese opera and waited at the door at home until she returned from school.

The photograph of Billie’s father shows him in formal dress with a wingtip collar and tie, and a slightly quizzical expression under thick eyebrows. He was an unusual Englishman who was born in Hong Kong, raised in Chefoo, spent his working life around China and retired in Tsingtao. He disregarded British social norms by taking a Chinese wife and adopting two non- Caucasian daughters. This would not have had a positive impact on Frank’s career in customs and the post office, but he earned the admiration of foreign communities, judging from a laudatory letter to the newspaper, and the respect of the Chinese who gave him several awards, including a silver star, for his services. His final position was Postal Commissioner in Chungking. Along his extensive travels, he became a scholar of calligraphy and antique curios. He gave talks and wrote articles about rare coins.

Frank Newman, Shanghai studio, date unknown. Image courtesy of Duncan Clark.

Frank sent Marylou to schools like St. Joseph’s and Shanghai Public School for Girls, where she excelled at studies and played hockey. But her privileged education came to an abrupt end in 1932 after Mama told her that her father, who had been absent for long periods, would not be returning. I have written about Frank Newman’ s complicated love life, and his relationship with a Russian woman.

Becoming a breadwinner at 16, Billie started as a teletypist for Reuters and a few years later became office manager for a new magazine, T’ien Hsia (Everything Under Heaven), that acted as a cultural bridge between east and west. Financed by the Chinese government, its editorial staff included intellectuals like Wen Yuan-ning, Lin Yutang, John Wu and T.K. Chuan, who had attended graduate schools in the west. Billie also met contributors like the American journalist, Emily Hahn, with whom she became a lifelong friend. The erudite magazine reflected a unique period of intellectual openness and international exchange that was interrupted when the Sino-Japanese war reached Shanghai in 1937.

Billie would have had more souvenirs of Shanghai between the 1920s and 1940s had not her life been disrupted several times in war and peace. She was seconded by T’ien Hsia to work for Shanghai Mayor O.K. Yui and was a newscaster for the government radio station XGOY) when Shanghai fell in August, 1937. Fearing she might be on a Japanese “black list,” she joined her colleagues in fleeing for Hong Kong. She had intended to return for Mama, but her mother died a few weeks later of a heart attack. A grief-stricken Billie returned to Shanghai and was on her way to Mama’s flat in Hardoon Road when she was interrogated by Japanese soldiers on Garden Bridge. The incident traumatized her and she had her mother’s belongings auctioned off in haste before returning to Hong Kong.

Billie was working for the Chinese Government Information Office, including being seconded to W.H. Donald, the Australian journalist who became an advisor to Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang, when the Japanese attacked Hong Kong in December, 1941. She became a prisoner of war in Stanley Internment Camp, going into camp with a baby boy and little more than she could carry. She came close to a nervous breakdown after losing her son in a drowning mishap on Stanley’s Tweed Bay beach. In the aftermath of the tragedy, her friendship deepened with an English journalist who would become my father.

Her upheavals continued after the war. She conceived me in Stanley and, after leaving the camp destitute, delivered me two months later in New Zealand. We spent a year in England with Emily Hahn and her husband Charles Boxer at their Dorset home, before Billie received a job offer from Hollington Tong to work again for the Chinese government in Nanking. We arrived during a period of hyper-inflation and hardship before she joined the United Nations Information Centre in Shanghai in early 1948. After a few more turbulent months, during which Billie nearly died from spinal meningitis, we were evacuated to Manila shortly before the Communist takeover in 1949.

Billie did walk me through her life in China. In 1975, we went to Hong Kong and Taipei to meet many of her childhood friends and ex-colleagues from Shanghai. We returned to Shanghai only in 1993 and, even then, she fretted the authorities might not allow her to leave. Shanghai had erased some of the more obvious reminders of colonial rule such as the race track but had yet to undertake large-scale redevelopment and much of Mum’s Shanghai was still there. Finding it was problematic, however, as streets and houses had aged prematurely through neglect and over-crowding and were difficult to recognize. Yuyuen Road, for example, had been a wide, leafy avenue with rickshaws, bicycles and the occasional motorcar in Mum’s memory, but was 60 years later a cacophonous mass of traffic.

Billie and her friend Edie had dinner with Pembroke Stephens (left) of The Daily Telegraph and O’Dowd Gallagher of The Daily Express.

Incredibly, she recognized T’ien Hsia’s railed balcony on which she stood when Daily Telegraph correspondent Pembroke Stephens shouted that Japanese troops were approaching in 1937. From there, she found her much-changed house further down Yuyuen Road. When Mum stood outside and talked animatedly, people gathered, including a tall, white-haired woman who spoke perfect, educated English. Margaret Lin was older than mother, had lived in the lane all her life and had been educated at McTyeire School for Girls. She and Mum hit it off instantly and Margaret joined our search. Without her, and amid the steady rain and the heavy traffic, we wouldn’t have found half the places that we did.

House at 3 Kiangwan Road, Shanghai, near the railway station where the Nationalists arrived in 1927.

Each location triggered an anecdote. At 3 Kiangwan Road in Hongkew, Billie peered into the front room and described the wedding reception for her sister Jessie on June 26, 1926, and how it ended abruptly when the groom, Jimmy Jamieson-Ellis, collapsed and was taken to hospital. A few months later, Billie remembered, Nationalist troops arrived via the Shanghai- Hangchow railway station around the corner and Frank moved the family to the International Settlement for safety. At Yuyuen Road the following year, Jimmy died of scarlet fever on July 19, 1927 and, a few nights later, all the lights mysteriously came on in the house and Jessie swore that Jimmy appeared to say goodbye. We also visited the former United Nations offices in Whangpoo (Huangpu) Road where Billie had started work in 1948 in a career that lasted until 1976, and for which she received an M.B.E. in 1977.

I started to entertain wild hopes that Duncan Clark might bring pictorial as well as anecdotal depth to our family’s close association with “Britain in China” that stretched back to Edward Newman career’s with the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company in Hong Kong during the 1860s. I have photographs of steep, narrow Old Bailey Street, where Edward and his family lived opposite Victoria Gaol, which is still there, and I retraced his steps down the hill to where the P&O offices had been on The Praya. Among the more amazing possessions my mother retrieved through our American cousins were a Masonic apron and patent which her grandfather Edward Newman had received at the Zetland Lodge in Hong Kong in 1872. I wrote about the Newmans’ bold gamble in 1873 when Edward and Mary Ann resettled in Chefoo, where they would own and run “The Family Hotel” while raising four children, including the son who would become “Uncle Frank” to the offspring of Duncan and Annie Clark.

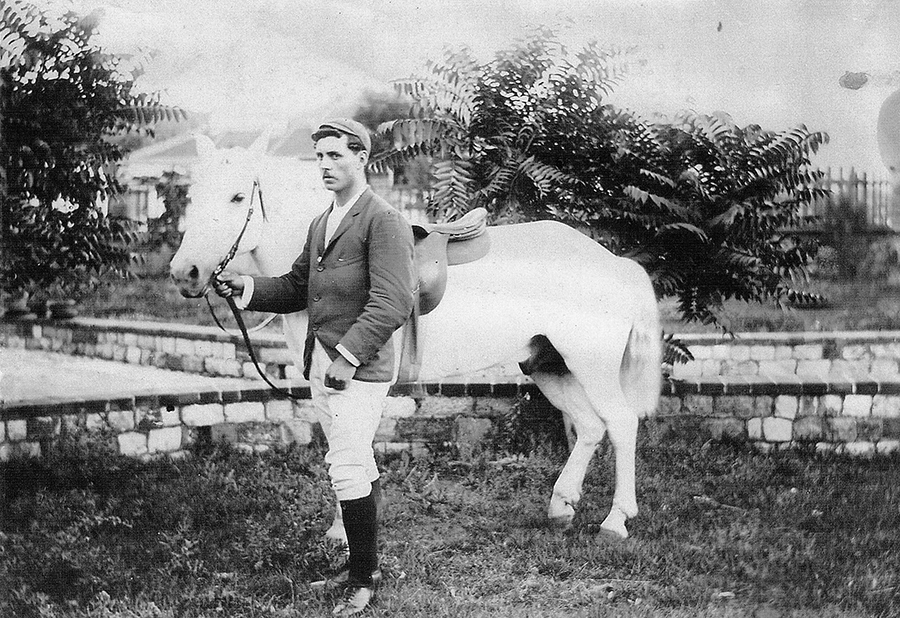

Over tea and sandwiches, I met grandson Duncan Clark at his home in June 2016. A thickset, dour man with a Scottish accent, Duncan was hospitable and generous in sharing his extensive family knowledge. He handed me an envelope with photographs of “Uncle Frank,” together with carefully- typed captions. They portrayed a young Frank I had not seen before. One showed a youthful, clean-shaven Frank with mustachioed Duncan Clark and James Glassey in a customs rowing team. Another depicts Frank in the attire of a gentleman jockey, complete with cap, holding the reins of a pony. This supplements an 1895 North-China Herald report on the Chefoo Races in which Frank won second place in the Duffers’ Derby on his own horse, a grey named Blossom.

Chefoo Chinese Imperial Customs rowing team. Frank Newman (far left), James Glassey (second from the left) and Duncan Clark (far right). Image courtesy of Duncan Clark.

Frank Newman won second place in the Duffers’ Derby in the 1895 Chefoo races. Image courtesy of Duncan Clark.

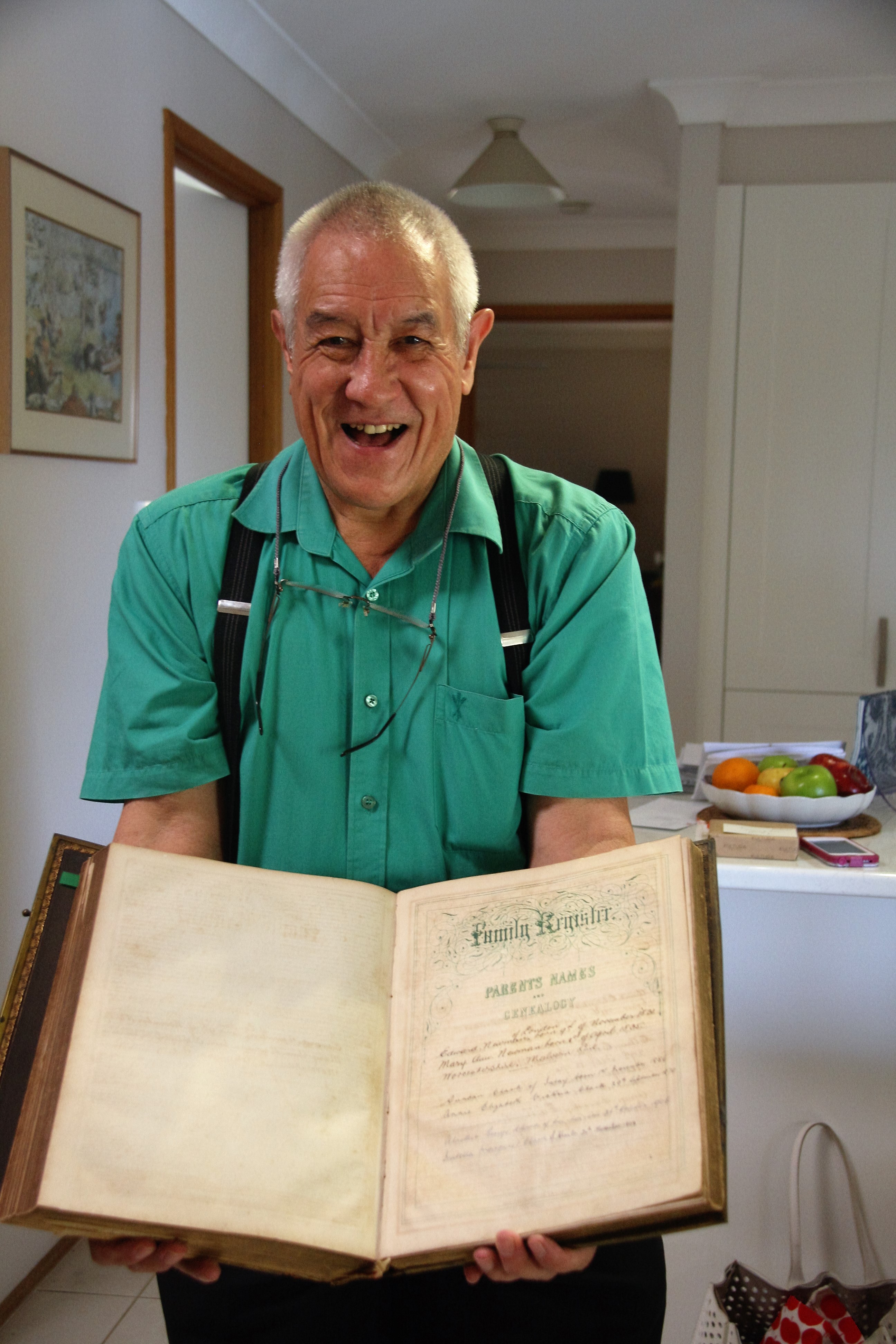

Duncan had no pictures of Edward and Mary, but he told me about another grandson of Annie and Duncan, Graeme Clark, who lived on the other side of the world. A burly retired Lieutenant-Colonel in the Australian army, Graeme, 73, was also keenly interested in family history. He lived in Queensland and we were soon talking enthusiastically on the phone about our family intersections. When Graeme said he had a Newman family Bible, inherited from Mary Ann through her second son George, it produced another goose bump moment. I thought it was likely to be similar to the family Bible Mum had inherited through Frank but which she had, inexplicably, given away to a friend before leaving Stanley camp.

Ian Gill holding the Newman Family Bible, with birth details of his great-grandparents Edward and Mary Ann Newman.

Graeme had Parkinson’s disease, but was managing reasonably well. A few weeks later, however, his condition took a dive. It was now or never, I thought, and I flew down to Helensvale on the Gold Coast where I was welcomed as one of the family by Graeme, his wife Frances and their daughter Victoria. As soon as I saw Graeme’s Newman family Bible, I understood why Mum could not have carried hers out of camp. It was huge and weighed 8 kilograms. I needed both hands just to hold it. Importantly, the Bible contained a dedication from Mary Ann Newman to her son in large, clear handwriting.

Though Graeme could not recall seeing photos of our great grandparents, I began browsing through his family albums Then, on a page marked “Hong Kong 1800s,” I saw, staring out at me, one photograph with the caption “Maurina Newman and her baby Annie” and another with the name Newman Edward, followed by a question mark. Since the only Newmans from our family in Hong Kong were Edward and Mary Ann, I had found what I had not dared to hope for. The image of little Annie, born in 1870, sealed the matter beyond doubt.

Mary Ann Newman, with baby Annie, Hong Kong 1870. Image courtesy of Graeme Clark.

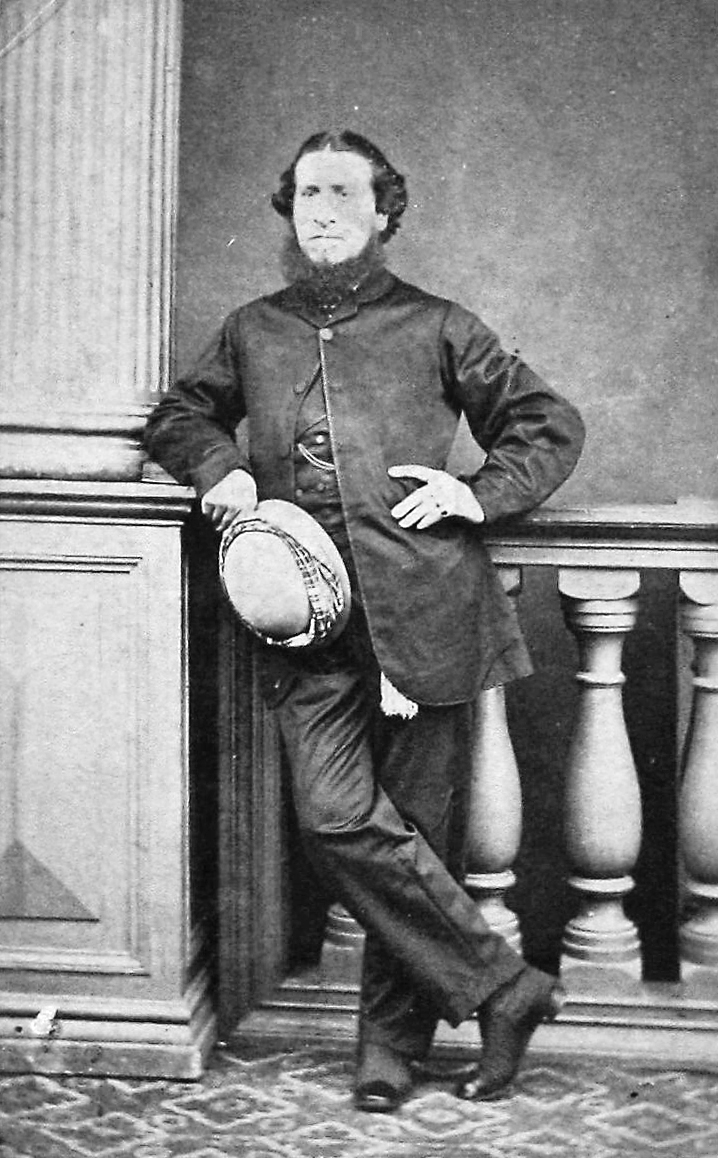

Edward Newman in Hong Kong, 1870. Image courtesy of Graeme Clark.

The postcard like-images, taken by a studio photographer, offer a glimpse of their characters before they made their epic move to Chefoo. Edward, with his jaunty stance, comes across as a derring-do type, while a seated Mary Ann looks calm and grounded as she holds Annie firmly on her lap.

I sent Mary Anne’s handwriting to a graphologist in Canada without giving any details of her background. The analyst deduced from Mary Ann’s script that she showed “strong thinking skills and balance.” In addition, she possessed “ability to organize. She can pull ideas, people or materials together into a functional force to get things done.” Interestingly, this jibed with Mary Ann’s experience as assistant manager at the Docks Hotel, part of the P & O complex, in Southampton. I also found two signatures of Edward Newman, one on the Masonic patent in 1872 and another when he registered his daughter Ellen’s birth in 1874 at the British Consulate. They were not a lot to work with but the graphologist noted that Edward’s signature extended significantly beyond the space allocated on the form. “It is normal for writers to respect margins. Edward does not,” she noted. “This is often an indicator of someone who may want to eliminate barriers between himself and the outside world; can be effusive in speech and obtrusive in manner; and could have a fear or a dislike of empty spaces. Edward has his own lifestyle and may be viewed by others as a bit of a non-conformist.”

Chefoo, from ‘Temple Hill’, 1900. Carrall Family Collection, Ca01-064, © 2008 Queen’s University Belfast.

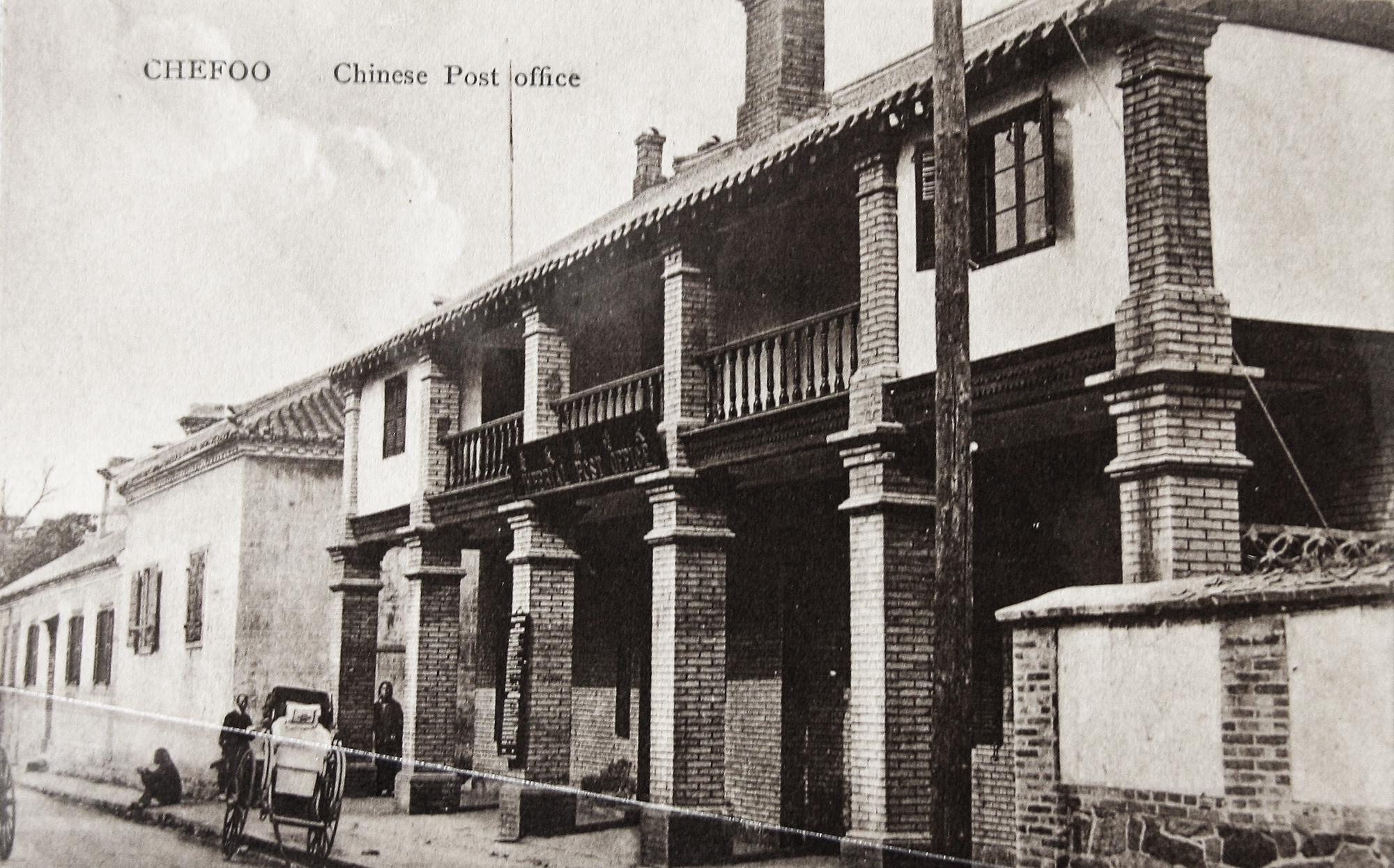

To find other visual pieces of the jigsaw puzzle, my wife and traveled to Chefoo, today known as Yantai, on China’s Shandong peninsula. Chifu is now a seaside district of the large, sprawling city of Yantai whose population has soared to 7 million from the 10,000 inhabitants of the walled Chinese city that greeted Edward Newman on his arrival. We met local historian Victor Wei Chunyang, who is familiar with the Newman family story and spent days taking us around the old foreign area. The stench of night soil has long dissipated since the 19th century, but the customs house and quay where the Newmans disembarked, the narrow streets, post offices and trading houses are preserved or restored, as are the British, Japanese, French and Danish consulates on Consulate Hill. St. Andrew’s Church has been demolished, leaving a circle of concrete stumps to mark its location.

Chinese Post Office, Chefoo. Post card courtesy of Lin Weibin.

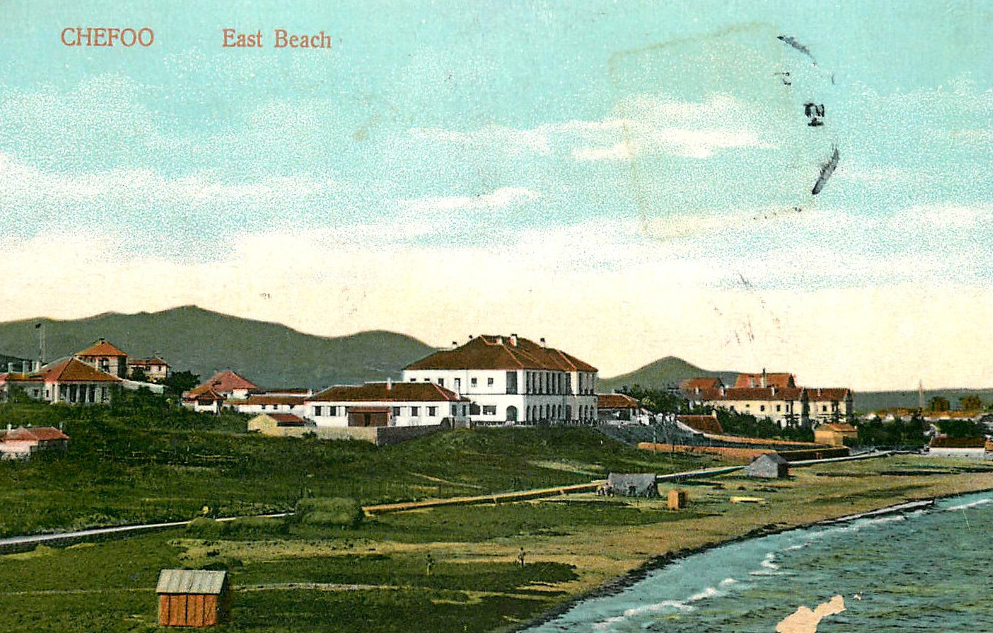

We took photographs but Victor Wei went one better, introducing us to his history- minded friends, including Lin Weibin, who has an extensive collection of postcards from the colonial era. Lin allowed me to photograph many of these postcards and credit them in articles, including this blog. It is thanks to Lin that I have images of “The Family Hotel”, both as a single-storey structure in its early days and later, after a second floor was added. I also have postcards of Chefoo’s East Beach where the hotel was located beside the China Inland Mission-built Chefoo School which the Newman children attended in the 1880s and 1890s.

“The Family Hotel” in Chefoo, owned by my great-grandparents. The C.I.M. Boys’ School is on the right. Postcard courtesy of Lin Weibin.

China Inland Mission Boy’s School, Chefoo, 1898. Carrall Family Collection, Ca01-025, © 2008 Queen’s University Belfast.

Wei took us to Temple Hill where Edward and Mary Ann Newman were buried in 1883 and 1891, respectively. Their graves were destroyed along with others during anti-foreigner outbursts in the Korean War but Duncan Clark gave me a poignant photo of Frank Newman standing beside the tombstones of his mother and father.

Frank Newman beside the grave stones of Mary Ann Newman and Edward Newman. Image courtesy of Duncan Clark.

Researching my family story turned unexpectedly into a grand adventure. It was magical to bond with long-lost cousins, and just in time, too, for Graeme Clark died not long after we met. I am indebted to my friend Victor Wei, of Yantai, who has shown great interest in my family. He unearthed much information about Frank Newman as well as interesting illustrations. One is a photograph of one of Newman’s rare coins, now housed in the National Museum of China in Beijing. Another is a picture of the citation accompanying a silver medal Frank was awarded by the Shaanxi provincial military government in 1921 for helping to bring a measure of stability during a chaotic warlord-dominated period.

Ian Gill is a Manila-based freelance journalist who began his career in the UK and has spent the past 46 years in the Asia-Pacific region working on staff for publications including the Asian Wall Street Journal in Singapore, Asiaweek and Insight in Hong Kong, the Fiji Sun in Suva and the Evening Post in Wellington, interspersed with a 20-year career at the Asian Development Bank writing on development in the region. He has a diploma in French studies from Geneva University, a BA in economics from Sussex University and an MA in educational communications and technology from the University of Hawaii. He is married with a daughter at McGill University and a son headed for Auckland University.